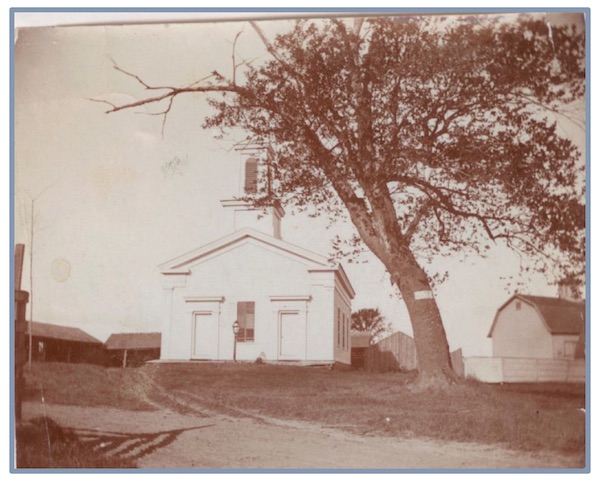

Town of Yates, celebrating 200th anniversary this year, was originally Town of Northton

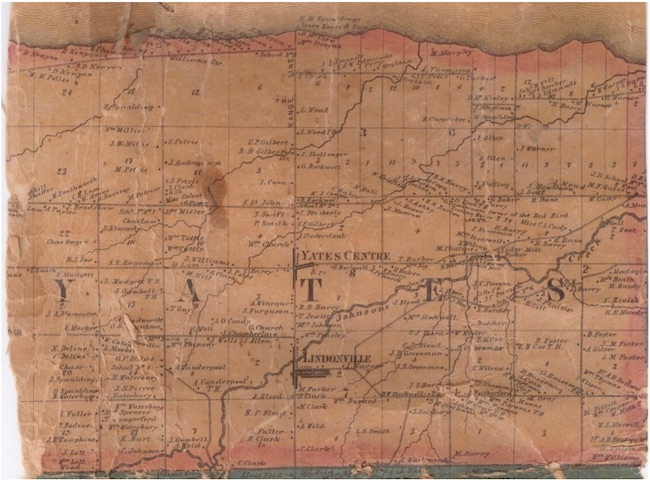

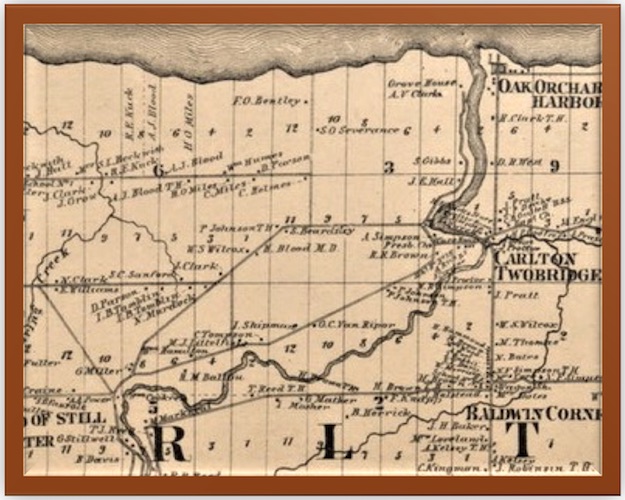

This 1860 map of the Town of Yates shows a robust settlement had developed in the first fifty years.

By Catherine Cooper, Orleans County Historian

Illuminating Orleans – Vol. 2, No. 11

YATES – A Bicentennial Committee in Yates is hard at work organizing family-friendly events in July, August, and September of this year, in celebration of the 200th anniversary of the formation of the Town of Yates.

Genesee County originally included Orleans County. This large tract of land was subdivided on June 8, 1812, with the formation of the Town of Ridgeway which then comprised the entire area of Orleans County included in the Holland Land Purchase. As the population grew, separate towns began to be formed or “set off.”

The Town of Yates was set off on April 17, 1822. Because of its geographical position, the town was originally called Northton, but this was changed in 1823 in honor of the Governor Joseph C. Yates, the eighth Governor of New York. Yates County was also named in his honor. (Were the same naming practices in vogue today, a newly formed town might be named the Town of Hochul.)

The Town of Yates has an area of 22,559 ½ acres. In 1812, it was heavily wooded with whitewood, beech, birch, oak, maple, and hemlock trees, many of which were over 100 feet high. In the book Landmarks of Orleans County, Isaac Signor refers to a huge white oak tree, which when cut, was drawn to Oak Orchard by fourteen yoke of oxen.

George Houseman of was the first permanent settler. He came from Jefferson County in 1809 and settled three miles east of what later became Lyndonville.

Preserved Greenman purchased 600 acres from the Holland Land Company between 1810 and 1812 and settled his two sons Daniel and Enos and daughter Chloe. Mr. Greenman’s brother, William B. and his two sons, Joseph B. and Stephen settled in the same vicinity. The area was known as Greenman’s Settlement. Though there are no longer Greenman’s locally, the memory of their presence is continued with the road named for them.

Other settlers before 1820 were: Robert Simpson, Nathan Skellinger, Comfort Joy, Zaccheus Swift, Lemuel Downs, Stephen Austin, Truman Austin, Daniel Stockwell, Rodney Clark, Amos Spencer, Samuel Whipple, Thomas Handy, Stephen Johnson, Thomas Stafford, Elisha Gilbert, Jacob Winegar, Isiah Lewis, Josiah Campbell, Samuel Wickham, Jeremiah Irons, Moses Wheeler, Benjamin Drake, Abner Balcom, Zenus Conger, Isaac Hurd, Harvey Clark and Horace Goold.

The Pioneer History of Orleans County, New York, by Arad Thomas, 1871 includes first-hand accounts of those early years. Horace Goold recalled:

“During the first season, we were sometimes short of food, especially meat, but some of the boys would kill a wild animal, and we were not very particular what name it bore, as hunger had driven us “to esteem nothing unclean but to receive it with thanksgiving.”

Samuel Tappan realized early on that farming was not his specialty:

“My fruit trees would fall down, and my forest trees would stand up; my crops were light, but my bill were heavy.”

He opened a tavern in Yates Center instead of farming was later appointed Postmaster and Justice. He married four times and had nineteen children.

Should you wish to read about the history of the Town of Yates in anticipation of the Bicentennial, the following publications are available at your favorite library:

- Landmarks of Orleans County, New York by Hon. Isaac Signor, 1894

- Historical Album of Orleans County, New York, 1879

- A History of the Town of Yates in Orleans County by Carol Dates Gardepe and Janice Dates Register, 1976.

- Also, the Town of Yates website includes a fine collection of photographs.

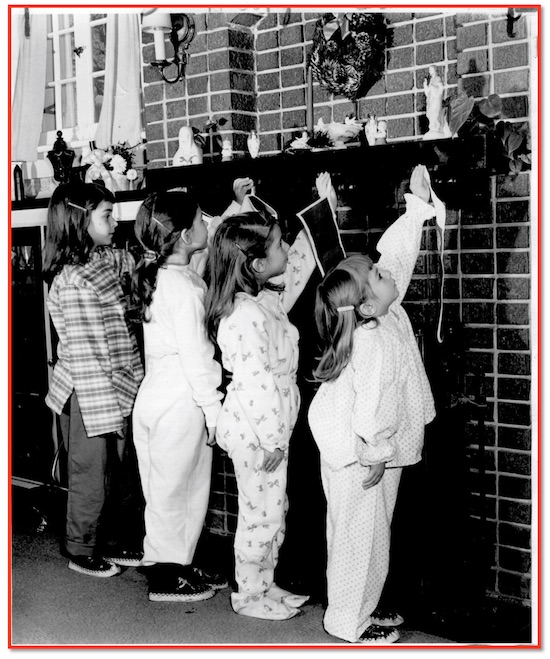

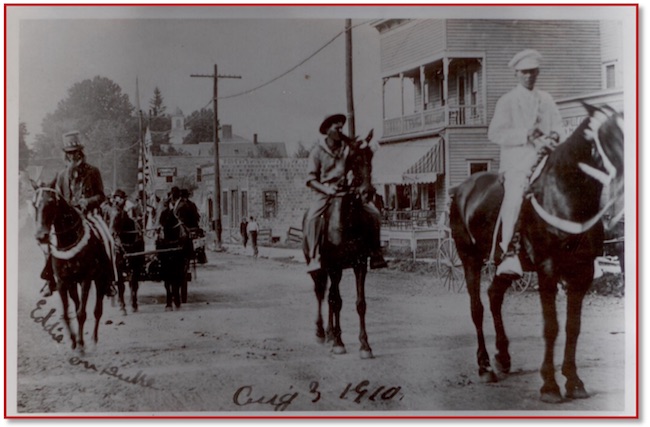

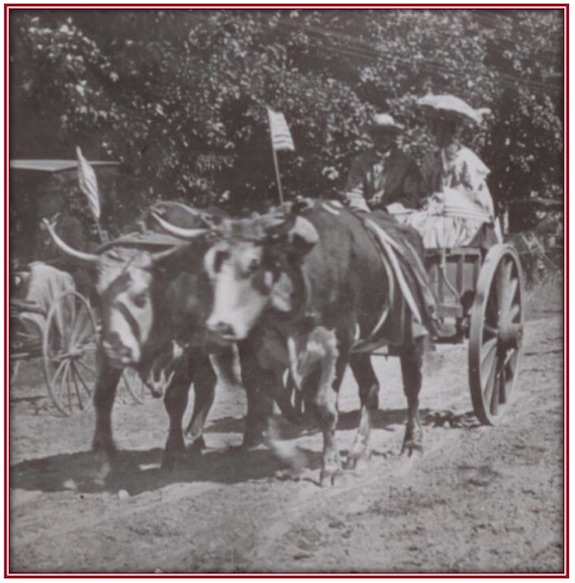

Our photograph from the Orleans County Dept. of History collection depicts the Fourth Annual Flower Carnival which was held in Lyndonville on August 2 and 3, 1910, under the direction of the Copia Society of the Methodist Church.

According to the Lyndonville Enterprise, the weekly newspaper:

“The parade surpassed any previous efforts and included many unique and handsomely decorated vehicles which were admired and cheered by the throng of spectators.

“Uncle Sam” was represented by E.M. Hill, who was accorded praise for being so suitable a figure for the occasion. The Lyndonville Hose Company, No. 1, with twenty-six men headed by the steam fire engine “White Elephant” drawn by four horses made an imposing appearance, while the Pioneer Drum Corps furnished music.

The float, conveying veterans of the S. and P. Gilbert Post of the Grand Army of the Republic, was prominent. It displayed a banner bearing the inscription:

“A few that made it possible for the many to enjoy”

MEDINA – George Kennan was indeed on home ground for this final lecture of a 200-lecture, nationwide tour. He had worked at the Union Bank, just across the street from Bent’s Opera House, in the 1870s. His home was on the same block, 127 West Center St., currently the location of the Canal Village Farmers’ Market.

MEDINA – George Kennan was indeed on home ground for this final lecture of a 200-lecture, nationwide tour. He had worked at the Union Bank, just across the street from Bent’s Opera House, in the 1870s. His home was on the same block, 127 West Center St., currently the location of the Canal Village Farmers’ Market.

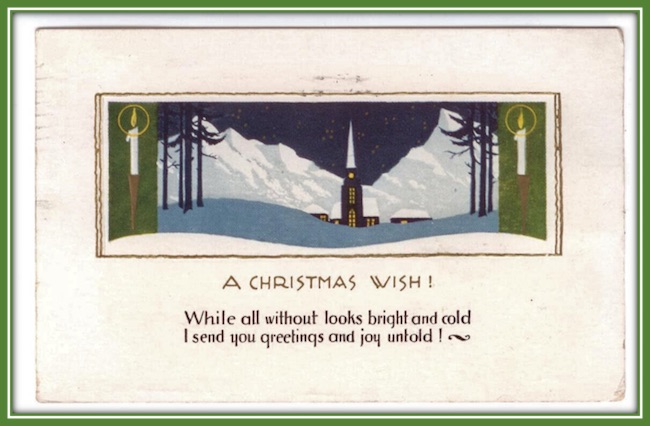

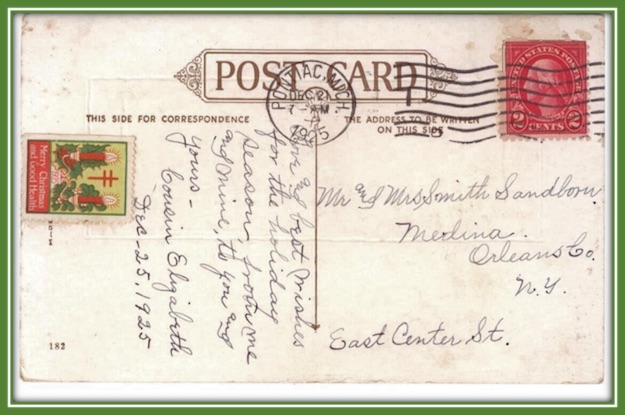

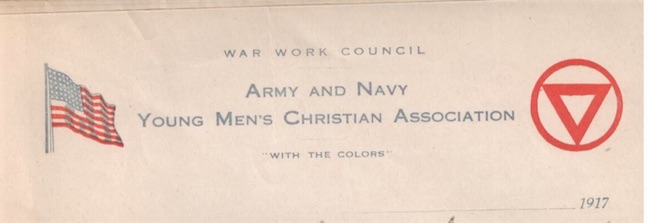

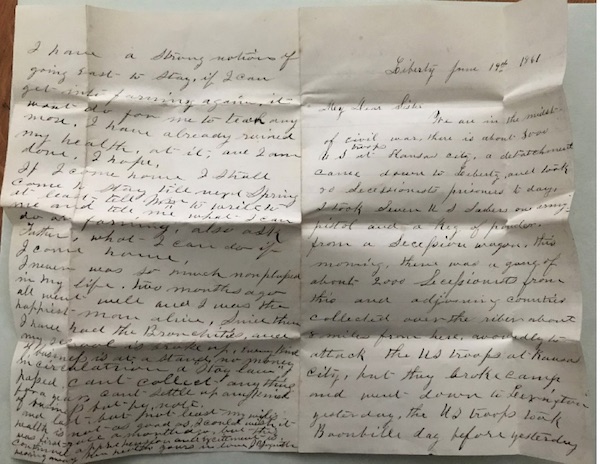

The letter pictured above includes the following passage:

The letter pictured above includes the following passage:

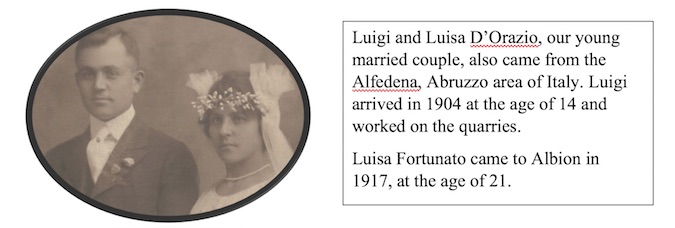

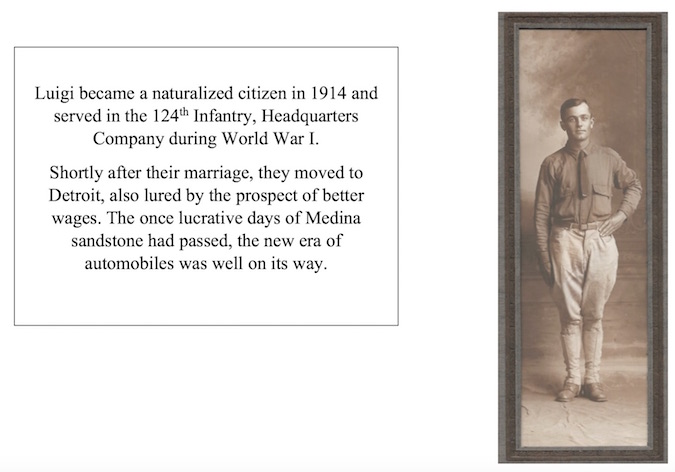

ALBION – Luigi D’Orazio and Luisa Fortunate, top left, were married on June 27, 1919, at St. Joseph’s Church in Albion, by Rev. Sullivan. The attendants were William and Teresa Sigisimondo, also of Albion. The calf-length hemlines and free-form design of the ladies’ dresses reflect the fashions of the day.

ALBION – Luigi D’Orazio and Luisa Fortunate, top left, were married on June 27, 1919, at St. Joseph’s Church in Albion, by Rev. Sullivan. The attendants were William and Teresa Sigisimondo, also of Albion. The calf-length hemlines and free-form design of the ladies’ dresses reflect the fashions of the day.

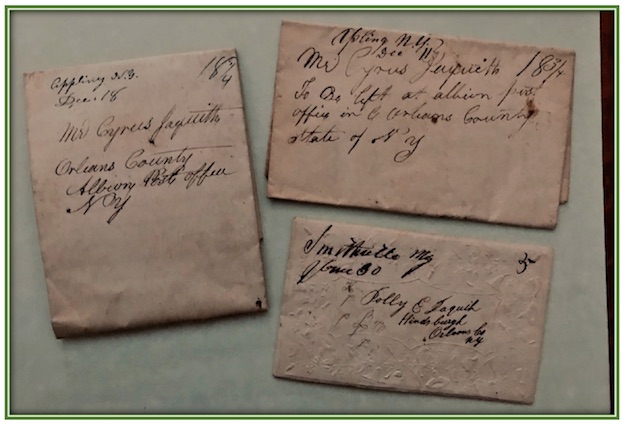

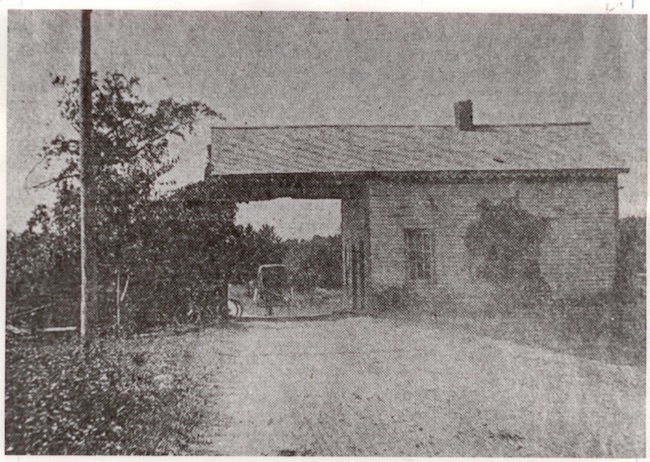

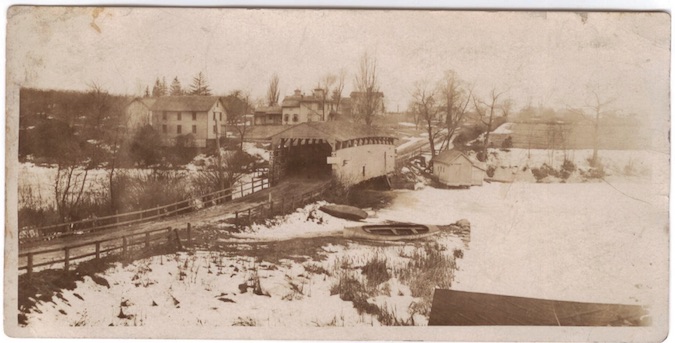

CARLTON – We have had the privilege of becoming acquainted with the daily lives of Hosea and Sarah Ballou on their farm on the Oak Orchard River Road in Carlton from Hosea’s diary entries, beginning in January 1851.

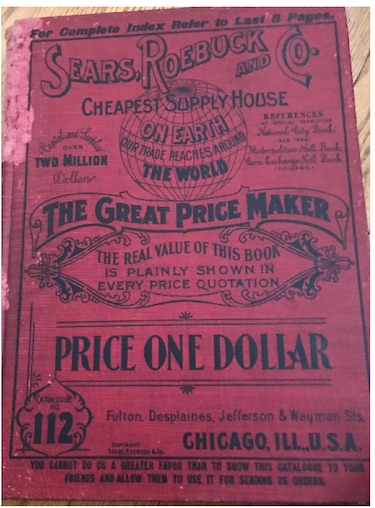

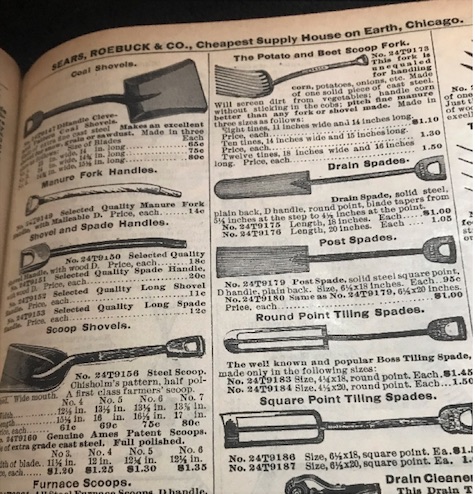

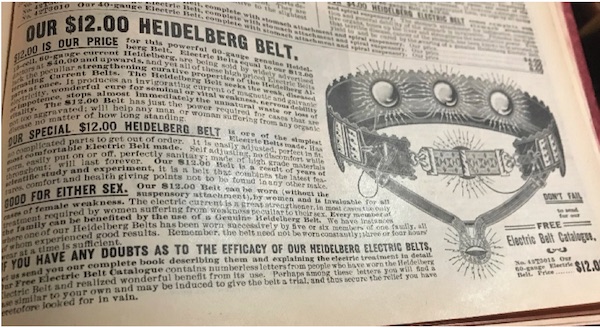

CARLTON – We have had the privilege of becoming acquainted with the daily lives of Hosea and Sarah Ballou on their farm on the Oak Orchard River Road in Carlton from Hosea’s diary entries, beginning in January 1851. Name a site where you could easily purchase any item under the sun, at a competitive price, allowing you to buy goods without going to a store and then have that item expeditiously sent to your home, availing of the most up-to-date transportation methods?

Name a site where you could easily purchase any item under the sun, at a competitive price, allowing you to buy goods without going to a store and then have that item expeditiously sent to your home, availing of the most up-to-date transportation methods?

CARLTON – In the year 1851, Millard Fillmore was the thirteenth President of the United States and Washington Hunt was Governor of New York.

CARLTON – In the year 1851, Millard Fillmore was the thirteenth President of the United States and Washington Hunt was Governor of New York.

CARLTON – Can you imagine living at a time when you would distinguish between “chopping wood at the door” and “chopping in the woods”?

CARLTON – Can you imagine living at a time when you would distinguish between “chopping wood at the door” and “chopping in the woods”?