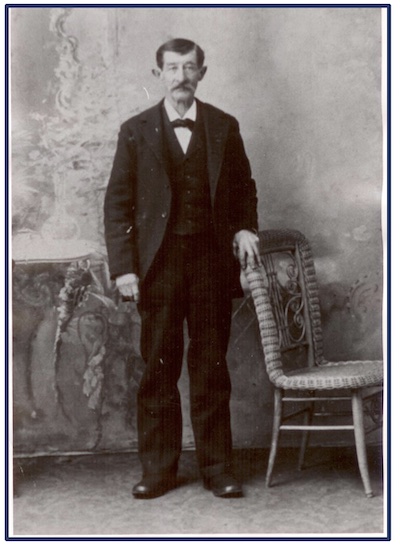

NYC native who built new life in Holley died from Spanish flu in 1918

Elbert Johnson, 30, was married with 2 young children

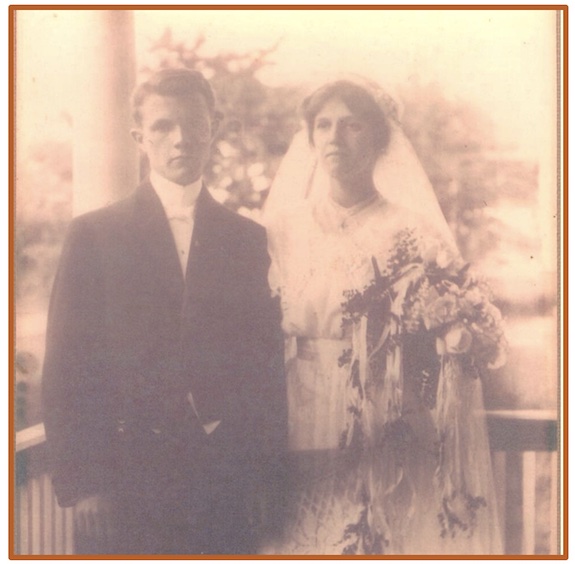

Elbert Johnston married Pauline Skinner on June 4, 1913

By Catherine Cooper, Orleans County Historian

“Illuminating Orleans” – Vol. 4, No. 6

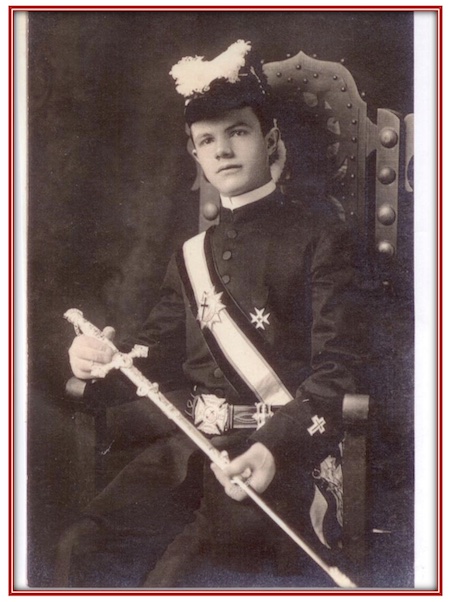

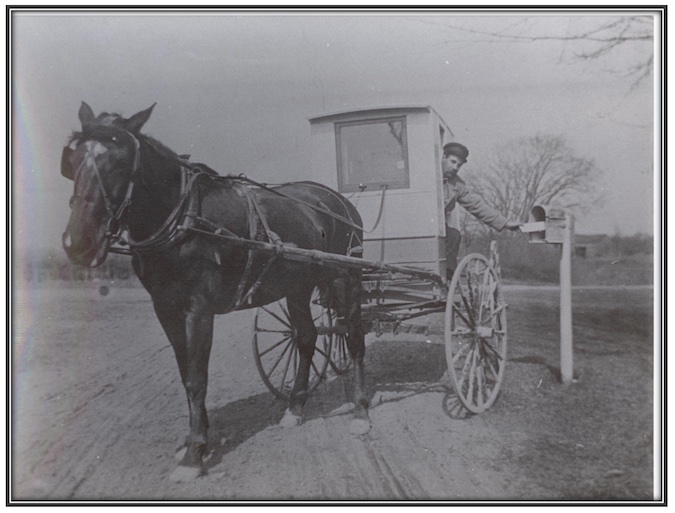

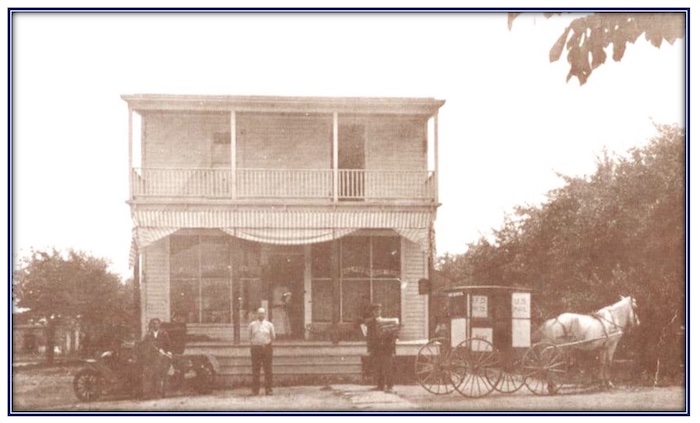

HOLLEY – Elbert Johnston, Part 2. In our previous column (click here), we read about Elbert’s move to Holley in 1907 from a journal that he wrote at that time.

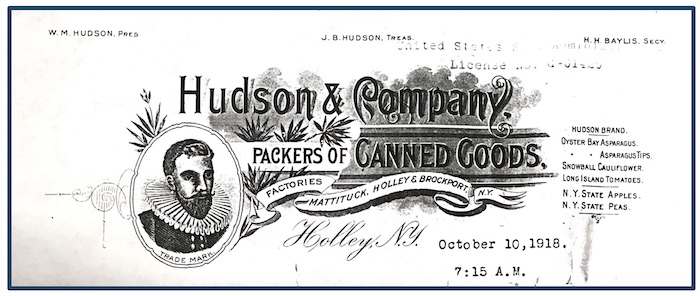

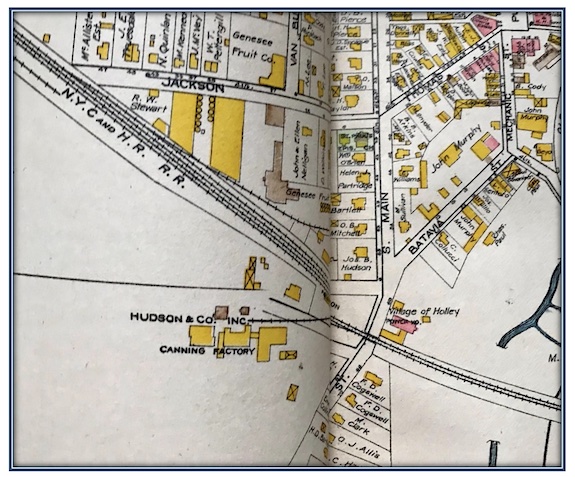

Elbert settled in to life in Holley and continued to work at Hudson Canning, the fruit and vegetable processing plant owned by his uncle, Joseph B. Hudson.

When Hudson Canning acquired the Batavia Canning Company plant in Brockport in 1910, Elbert was appointed superintendent. Elbert also managed the Holley plant when his uncle went to Long Island to attend to the original Hudson Canning plant in Mattituck in Suffolk County.

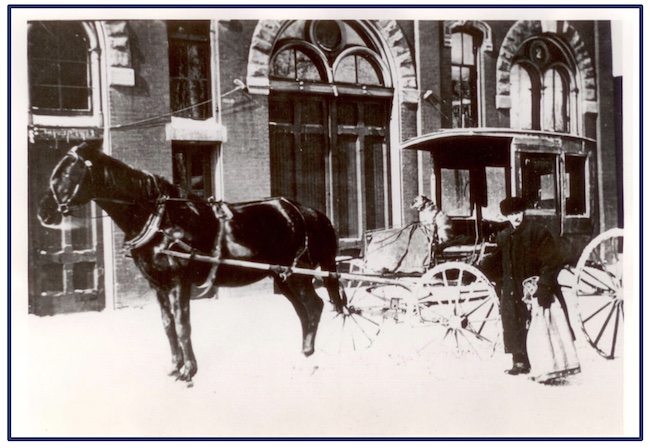

Elbert married Pauline Skinner on June 4, 1913. Born in Rochester on July 6, 1889, Pauline was the daughter of DeWitt and Stella Skinner. Pauline worked in the office of the Shinola Company, a Rochester based company which produced boot and shoe polish.

The couple was engaged on New Year’s Eve, 1912, following a courtship of six months. The wedding took place at Pauline’s home, 209 Flower City Park, in Rochester, on June 4, 1913, with about sixty guests in attendance. Elbert was then aged 26 and Pauline was 24.

“The bride wore a gown of white voile trimmed with ratine lace, made over white silk and carried a shower Bouquet of Bride roses and lilies of the valley….The groom’s gift to the bride was a gold monogram watch and pin.”

A wedding supper was served following the ceremony. According to a family story, an ice-cream maker set up on the front porch was snatched by young boy, but the bride’s father chased him down the street and retrieved it.

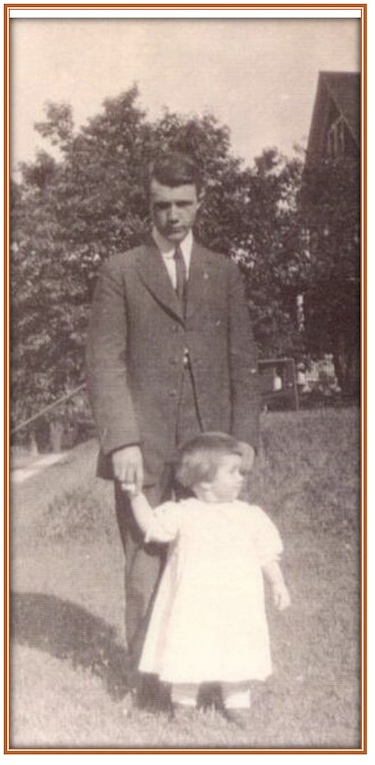

Elbert Johnston photographed on Sept.1, 1918, with his daughter, Arietta Jean, born March 9, 1917.

The couple honeymooned in New York City and lived in Brockport at first, but later moved to Holley, to a house across the tracks from Elbert’s uncle’s home.

Pauline assisted with office work at the canning factory.

Their daughter, Arietta Jean, was born on March 9, 1917, at Park Ave. Hospital in Rochester. Pauline had stayed with her parents for two weeks before the birth, to be close to the hospital. Elbert visited frequently. Arietta was named for Elbert’s mother, Arietta Hudson Johnston.

Pregnant with their second child, Pauline went to stay with her parents in Rochester again, in September 1918. Arrietta accompanied her.

A letter, which Elbert wrote to Pauline on Wednesday, September 25, 1918, survives. It is full of the details of their everyday lives. Elbert wrote that he brought some wood home and set a fire in the kitchen as the house was damp, gathered dandelions for the rabbit’s breakfast and cleaned the hutch. Lad, their Irish setter dog, spent a lot of time at the office, sleeping at the back of the stove. He included a snippet of gossip: “Chet and his wife are separating.” Elbert enquired after Arietta Jean and wrote that he would see them on the coming Sunday.

Their son, Robert Walter, who was named for Robert Burns and Sir Walter Scott, was born on Saturday, September 28, 1918. But when Elbert went to visit on Sunday, as promised, he was denied entry. Visitors were not allowed at the hospital on account of the Spanish flu epidemic.

Within a week, a quarantine was declared in Holley where the flu was rampant. Elbert contracted it. His Aunt Allie cared for him, but he died on October 18, 1918, just shy of his thirty-first birthday, having been ill for just one week. He was buried at Riverside Cemetery in Rochester.

His son, Robert Walter, was two weeks old. Elbert had not had an opportunity to see him because of the quarantine. Arietta Jean was nineteen months old.

Following Elbert’s death, Pauline remained in Rochester with her parents. She never returned to their home in Holley, which was sold. Later, since she needed to earn a living, and was an accomplished seamstress, she took a correspondence course in dressmaking and started a business.

This poignant tale is sourced from items graciously donated to the Orleans County Dept. of History by Gail Wadsworth, daughter of Arietta Jean. Considering the domestic upheaval surrounding Elbert’s death and the fact that Pauline moved house several times, it is quite remarkable that these items survived.

True, this material just provides details on the life and death of one individual. But from a local history point of view, its significance is that it helps us understand the great events of the time. It also points to the role of the local history entity in the preservation of such unique and irreplaceable documents.

In our previous column, we mentioned that Elbert and some friends attended a Political Suffrage program in Holley in 1907. It is apparent from Elbert’s comments following the event that he was not in favor of women’s suffrage, which is surprising, given that he was a modern young man from New York City who enjoyed the company of young ladies. His stance starkly indicates the daunting negativity and prejudice that faced the suffragists.

We can read that 65,000 people in the United States died from the Spanish flu, but when we read about a relatable individual, a healthy young man from Holley who succumbed having been ill for a week, we realize how virulent it was and the long-lasting impact it had on so many families.

Incidentally, at one point, Pauline and her family were neighbors of the Reverend Randall Kenyon family, whose housemaid was May Howard, a young English girl, one of the survivors of the Titanic, who is buried at Boxwood Cemetery, Medina…but that’s another story.

Here are instructions from The White House Cookbook (1900 edition) on how to cook a roast turkey: Select a young turkey; remove all the feathers carefully, singe it over a burning newspaper on the top of the stove, then “draw” [clear the innards] it nicely, being very careful not to break any of the internal organs; remove the crop [pouch at the base of the neck which may contain food] carefully; cut off the head, and tie the neck close to the body by drawing the skin over it.

Here are instructions from The White House Cookbook (1900 edition) on how to cook a roast turkey: Select a young turkey; remove all the feathers carefully, singe it over a burning newspaper on the top of the stove, then “draw” [clear the innards] it nicely, being very careful not to break any of the internal organs; remove the crop [pouch at the base of the neck which may contain food] carefully; cut off the head, and tie the neck close to the body by drawing the skin over it.

YATES – In the 1970s, a second rural Orleans County site was considered as the location of a nuclear facility.

YATES – In the 1970s, a second rural Orleans County site was considered as the location of a nuclear facility.

KENDALL – In the mid-1960s, a site in the Town of Kendall was considered as the possible location of an atomic research laboratory.

KENDALL – In the mid-1960s, a site in the Town of Kendall was considered as the possible location of an atomic research laboratory.