Medina building, originally a cold storage built in 1901, saw mysterious death of owner in 1904

By Catherine Cooper, Orleans County Historian

Illuminating Orleans, Vol. 3, No. 13

MEDINA – Medina’s Main Street buildings have been photographed at different times and from every possible angle, with the glaring exception it turns out, of 613-615 Main Street, the former cold storage building damaged by fire on April 7.

While the red trim of recent years accented the rounded entrance and ground floor windows, this functional monochromatic building just could not compete visually with adjacent structures. The recent fire has made us more aware of the building, how its heft anchors Main Street, how its bulk now seems reassuring and what a gaping hole it would leave if demolished, as the loss of the buildings at the “Four Corners” did in 1971.

Cold storage buildings, like barns, are visual records of our agricultural heritage. Built of fieldstone and architecturally unremarkable, these large warehouse-type structures were built around the turn of the century in every village or hamlet that had a railroad depot. The ability to extend the shelf life of produce and to have more control over market fluctuations contributed significantly to the agricultural economy.

The Main Street Cold Storage was built in 1901 by Frank Austin and Charles Dye. The three-story structure and basement comprised 24,000 square feet, and it was the first fully mechanized cold storage in the area. Apples, pears and peaches were the principal fruits stored.

But a tragedy occurred there soon after construction. Frank Austin was killed on September 23, 1904, when he fell through the elevator shaft. The Medina Daily Journal reported the story in detail:

“About a quarter after eight last night, the night watch, Bill James, left the building and went to the Opera House to attend the show. He claims to have left everything all right, even going over the entire building to see that the temperatures in the various rooms would hold till the play was over, and that things in general were safe to leave for the three hours that the entertainment would likely last.

“Upon returning, James, and Mr. Austin’s son, Floyd, who had also been at the play, found the outside door of the storage open and no lights burning. They at once started to investigate and finally found Mr. Austin at the bottom of the elevator shaft, lying against the side of the wall. His coat was over his head and a bicycle, which belongs to his daughter, which stood outside of the building where his son had left it when he went to the show, was lying on top of him.

“A physician was at once sent for and the police notified. It was found that there were still signs of life, but he never regained consciousness. A few hours later, he was moved to his home on West Ave., where he was attended to by Drs. Turner, Rogan, and Whiting, who found that the back of his head was crushed in.

“Mr. Austin was one of Medina’s most enterprising businessmen, having moved here from Shelby a few years ago.

“His keen business instincts assured success from the start, and the farmers of this section have lost a business friend who they are sure to miss.

“Mr. Austin was forty-six years old and left a wife, two daughters, Misses Fern and Onieta, and one son, Floyd.”

As an aside, the press presentation of this story is interesting. The Medina Daily Journal of September 24, 1904, ran this sensational headline:

However, the article clearly states that these dramatic suppositions were unfounded:

“An examination revealed the fact that he had fifty dollars in his hip pocket and a number of valuable papers in his inside vest pocket. There was nothing to show that there had been any attempt whatever at robbery. Throughout the whole building there was not the least sign of any struggle, and the conclusions point to accident.”

The Medina Tribune headline was less sensational:

It includes an account of the inquest. Coroner Munson concluded that the death was the result of an accident “however mysterious it may seem.” He concluded that the unfortunate man, finding his son’s bicycle outside as he started to leave, carried it in, and fell down the elevator shaft, while groping about in the darkness.

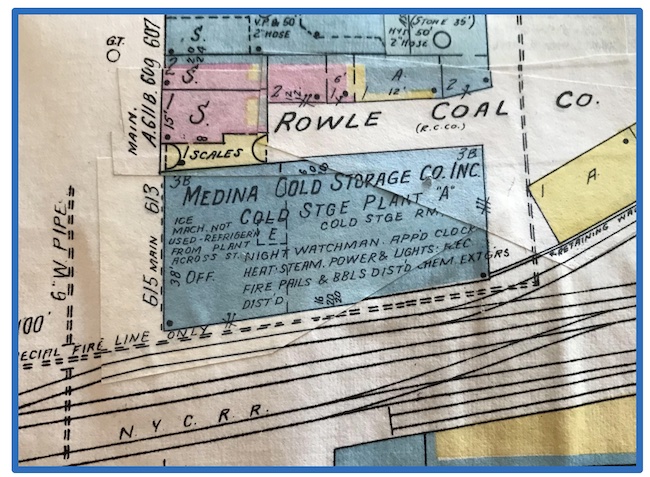

Following Mr. Austin’s death, the company was re-organized in 1907 as the Austin & Rowley Cold Storage, with Irving G. Rowley, President; F.W. Floyd Austin, Vice-President; and Frank A. Rowley, Secretary/Treasurer.

In addition to cold storage, the business acted as an agent for the International Harvester Company, selling and servicing agricultural machinery such as hay balers, manure spreaders and mowers.

They also sold cars. In 1910, they promoted the Studebaker wagon and in 1916, Maxwell, “The Wonder Car”, which cost $655. The Austin & Rowley enterprise prospered and expanded to include two other buildings. However, in the late 1920’s, lighter apple crop yields reduced revenue and a foreclosure sale was eventually necessary to satisfy three mortgages totaling $92,000, which were held by Charles Dye and the Central Bank of Medina.

On August 1, 1928, Claude W. Grinnell and J.C. Posson, principal stockholders of the Medina Cold Storage Company, purchased the Austin Rowley Cold Storage plants for $100,000 (currently $1.8 million approx.). This was not the most auspicious timing for such an investment, but the Medina Cold Storage weathered the Depression and even expanded in the 1940s.

The building’s long connection with cold storage ended in 1973 when it was sold to Jeff and Hugh Fuller who moved Nu Floor, a floor covering business there from 410 Main St.