South Barre was home of ‘Water Cure’ site about 150 years ago, boasting healing powers

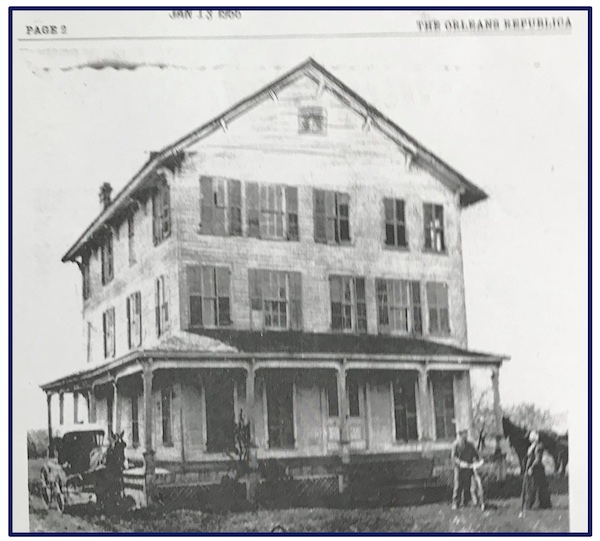

Photographs of the South Barre Water Cure are rare. This image appeared in the Orleans Republican, Jan. 13, 1966

By Catherine Cooper, Orleans County Historian

Illuminating Orleans, Vol. 3, No. 11

BARRE – The curative powers of drinking and soaking in mineral waters were acknowledged by the ancient Greek and Romans. In 18th century England, visitors flocked to the city of Bath to partake of its hot spring mineral waters.

Vincenz Priessnitz (1799-1851), an Austrian who is considered the founder of modern hydrotherapy, popularized the concept of water-cure establishments which combined various forms of water treatment with rest, exercise and clean air.

This concept of hydrotherapy as an alternative medicine became popular in the United States during the 1840s and 1850s. At a time when public water was often contaminated and the source of disease – when mortality was high and antibiotics yet unknown – this was quickly accepted as a viable treatment for a variety of acute conditions: gout, liver ailments, stomach inflammation, rheumatism, and skin disorders.

The treatment regimen usually involved drinking copious amounts of special or “pure” water, taking cold showers, cold baths and being wrapped in cold sheets.

Soon most communities in New York State could boast a “water cure”. In Western New York, mineral spring resorts opened at Alden, Avon, Castile, Chautauqua, Clifton Springs, Cold Springs, Cuba, Dansville, and Wyoming. By 1900, sixty-four such resorts had been opened in New York State.

Two water cure locations operated in Orleans County. The Alabama Sour Springs also known as the Oak Orchard Sour Springs is familiar to many. The Water Cure which operated in South Barre is less well known. Located in the Town of Barre, on the south side of Oak Orchard Road where the road runs east and west, and just north of the mucklands, it was short-lived and seemingly only established by default.

As befitting its location on the edge of the mysterious Tonawanda Swamp, the circumstances surrounding the establishment of the Water Cure are murky. Visions, mediums, spiritualists, petroleum wells, large sums of money and exaggerated claims were involved.

In some accounts, Mrs. Sarah Collins, a wealthy widow from Genesee County whose married daughter lived in Barre, claimed to have received communications from the spirits who instructed her to drill for oil at a specific location out in the swamp. In 1868, she hired an experienced team of men who drilled to a depth of 1,400 feet with no success.

The spirits then advised her to drill at another location at the edge of the swamp. Having drilled to a depth of 1,200 feet, the drill team did not find oil but discovered “a flowing stream of water which had a strong and unpleasant odor”, which, according to the spirits, possessed medicinal properties.

However, a lawsuit outlined in the Democrat and Chronicle of Friday, June 17, 1877, indicates that it was Jeremiah Eighmie, a wealthy spiritualist from Dutchess County, who financed the drilling, having purchased the 1,500 acres of swampland from Ezra B. Booth on the recommendation of Mrs. Collins and her spiritual advisors. He claimed that the “valuable deposits” of coal and oil promised were falsely represented and he sued to recover damages for his investment of $20,000.

The construction of the “Water Cure”, as it was locally known, is attributed to the ever resourceful Mrs. Collins. It was an imposing three-story structure, about 200 feet wide and 300 feet long, located close to the wells where the curative water had been discovered. A first-class sanitarium facility was located on the first floor. Parlors, reception rooms, dining halls and sleeping quarters were also outfitted.

The building boasted a central heating system: heat produced by a large pipe-less furnace in the basement rose through a large floor register in the first-floor main entry area and then through floor and ceiling registers to the upper floors.

Three windmills were erected at the wells, iron pipes were laid underground to carry the water to the hotel. The acidic spring water or “sulphur water” prevalent throughout the Tonawanda Swamp area is the product of geochemical processes involving the oxidation of organic carbon and pyrite. It smells rank, tastes foul, and is so acidic it can curdle milk. Its curative properties are dubious at best. But at that time, it was convincingly presented and advertised with ringing testimonials. It is likely that any improvement experienced by clients was due to the change of scene, clean air, and rest.

The Water Cure enterprise at South Barre was short lived due in large part to the untimely death of Mrs. Collins, its principal investor. Regardless of its purported curative properties, its location, eight miles from the nearest railroad station in Albion, was a deterrent for prospective clients since many other such establishments were more easily accessible.

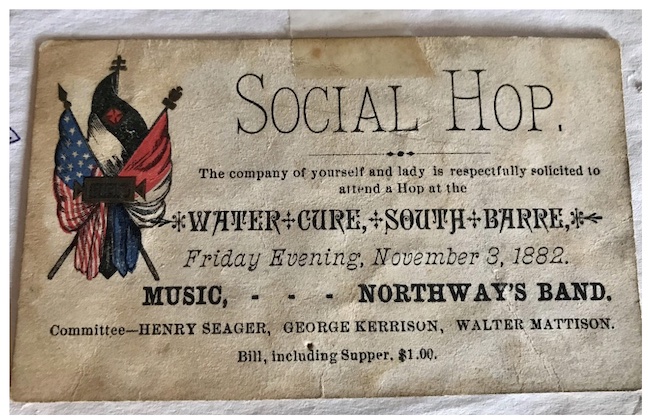

The cost – $1 per couple for supper and dance – would approximate to $30 today.

In later years, the building hosted local dinners, dances, and social events. Local young men: Henry Seager, 21, George Kerrison, 17 and Walter Mattison, 18, organized this November 3, 1882 “Social Hop”. George Gibbs owned the property from about 1890 to 1915, it later burned.