Former store in Millville served as hub of rural hamlet

By Catherine Cooper, Orleans County Historian

Illuminating Orleans – Vol. 2, No. 27

It is in Western Orleans, on a main route. We tend to pass it by (at the legal speed limit of 40 mph, of course), intent on getting to somewhere else.

At one time it was the hub of this rural hamlet, strategically located at a crossroads. Sturdily built of local limestone, it still stands at the intersection, basically unchanged, apart from the front porch which is now concrete.

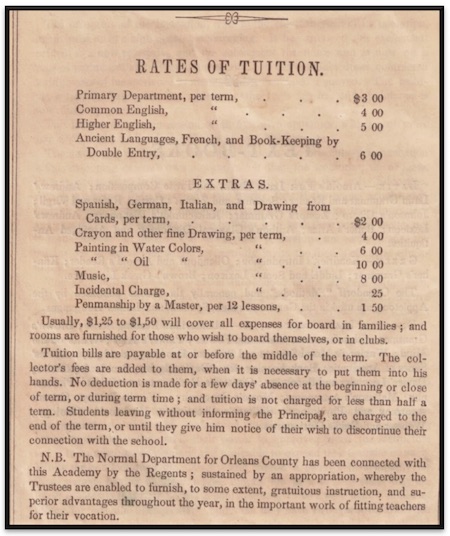

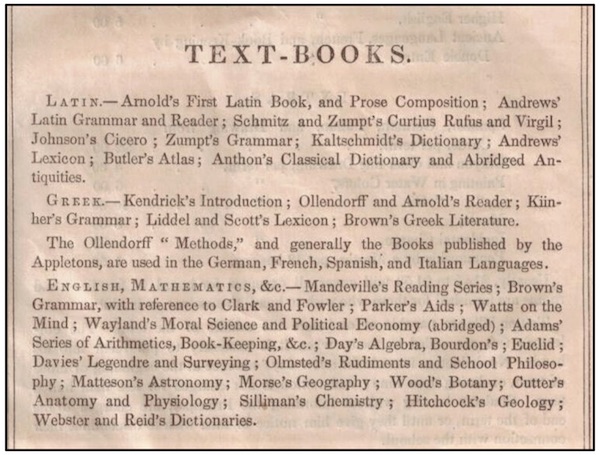

The T.O. Castle & Son Mercantile operated in the Town of Shelby hamlet of Millville from 1849 to 1933. Located at the intersection of Maple Ridge Road and the East Shelby Road, it served the surrounding rural community as well as the staff and students of the nearby Millville Academy.

Though fortunate in its location, it seems that the character and personality of its owner, T.O. Castle, played a part in its success. We do not have a photograph of this enterprising gentleman, but we can glean a good deal of information about him from various sources.

T.O. (Thomas Oliver) Castle was born in Parma, Monroe County on April 2, 1826, the son of Jehiel and Nancy (Willey) Castle. He taught school for two years. In 1846 he moved to Shelby Center in Orleans County. He worked at the store owned by his uncle, Reuben S. Castle. He then worked in Buffalo for two years as a supervisor of salesmen at the George M. Sweeney store.

According to the U.S. Army Mexican War Enlistments Records 1847-49, he had hazel eyes, sandy hair and was 5’6” tall. He married Mary Timmerman, daughter of Catherine Timmerman, in December of 1850.

The store’s signs and advertising refer to 1849 as the year of establishment, though the deed recording the purchase of the property is dated March 20, 1851. It is interesting to note that the property transfer was made to Mary Ann Castle.

T.O. Castle was Postmaster from 1853 to 1857 and later from 1878 to 1897. He was a Justice of the Peace and served as a Justice of Sessions. He was secretary of the Board of the Millville Cemetery Association. He was on the fundraising committee for rebuilding the Congregational Church.

According to the 1862 IRS Tax Assessment List, he is listed as a Retail Dealer. He owned one horse and carriage. In 1866, his carriage was valued at $80. He also owned a melodeon valued at $125 and a gold watch valued at $100.

At that time, the Medina newspapers published local news items from the surrounding towns. T.O. Castle’s business, community and personal activities were frequently mentioned in the reports from Millville:

- “T.O. Castle visited his daughter, Kittie, living in Syracuse.” – Medina Tribune, Feb. 26, 1874

- “T.O. Castle has threshed forty-one bushels and a half of wheat to the acre, being ahead of his neighbor Homer Sherwood one- and one-half bushels.” – Medina Tribune, Aug. 6, 1877

- “T.O. Castle nominated as Justice of Sessions at the Democratic Convention held at Albion.” –Medina Tribune, Oct. 18, 1877

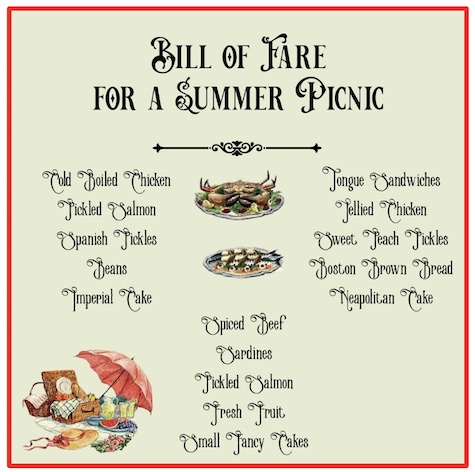

- “T.O. Castle served on the Refreshments Committee of the Arrangements for the Re-Union of the 28th Regiment.” – Medina Tribune, May 13, 1880

- “T.O. Castle has been remodeling his store on the inside, having repapered it, ceiling, and all, put in new shelves, and is now painting all of it which is a great improvement. He has also given notice to those who have been hanging around that it must be stopped.” – Medina Register, Feb. 18, 1892

- “Pneumonia is prevalent in the county. The family of T.O. Castle has been especially stricken. Two members, Mrs. Castle and her mother, succumbed within twenty-four hours.” – Buffalo Morning Express, Feb. 6, 1897

- “T.O. Castle suffering from severe attack of arthritis.” – Medina Tribune, July 30, 1903.

His obituary in the Medina Daily Journal of March 30, 1910, noted that “he was widely known and esteemed.” Following his death, the store was taken over by his son, George D., who operated the store until his death at the age of 81 in 1933.

Daniel Hurley, the present owner, has a genuine enthusiasm for this building and its past. He hopes to restore it to the point where people will want to stop and enter rather than just speed on by.

ALBION – Local history matters. Many major international events may seem on the surface to have little connection to our rural communities but when the evidence is explored it becomes clear that many impactful individuals have called Orleans County home.

ALBION – Local history matters. Many major international events may seem on the surface to have little connection to our rural communities but when the evidence is explored it becomes clear that many impactful individuals have called Orleans County home.

MURRAY – June 10, 1933. A quiet Saturday night on Route 104 in rural Sandy Creek, in the Town of Murray.

MURRAY – June 10, 1933. A quiet Saturday night on Route 104 in rural Sandy Creek, in the Town of Murray.

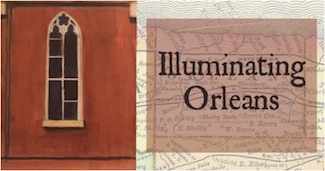

Selina had acquired nursing experience working with her brother Dr. Nathan Porter Johnson. She served under Dorothea Dix from September 1862 to July 1865. She contracted typhoid in March 1863 and came home to recuperate but returned to Washington in the fall of 1864. She worked in Georgetown, Washington D.C., Alexandria, Chesapeake, and Old Point Comfort, Virginia.

Selina had acquired nursing experience working with her brother Dr. Nathan Porter Johnson. She served under Dorothea Dix from September 1862 to July 1865. She contracted typhoid in March 1863 and came home to recuperate but returned to Washington in the fall of 1864. She worked in Georgetown, Washington D.C., Alexandria, Chesapeake, and Old Point Comfort, Virginia.

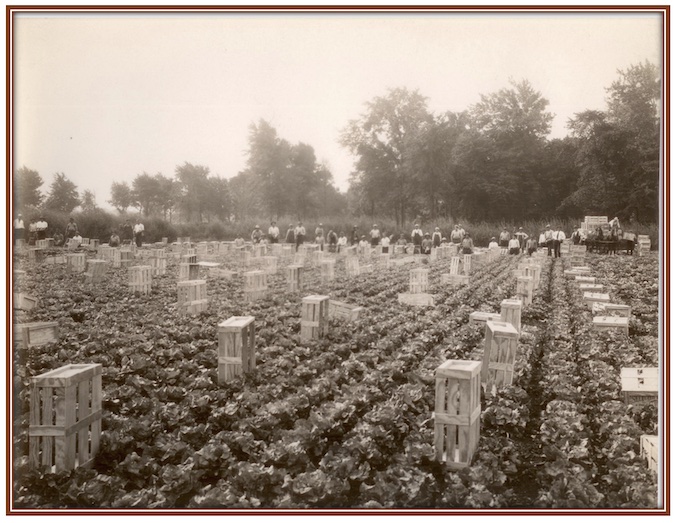

BARRE – The newly drained Tonawanda mucklands in southern Orleans County proved to be very productive.

BARRE – The newly drained Tonawanda mucklands in southern Orleans County proved to be very productive.

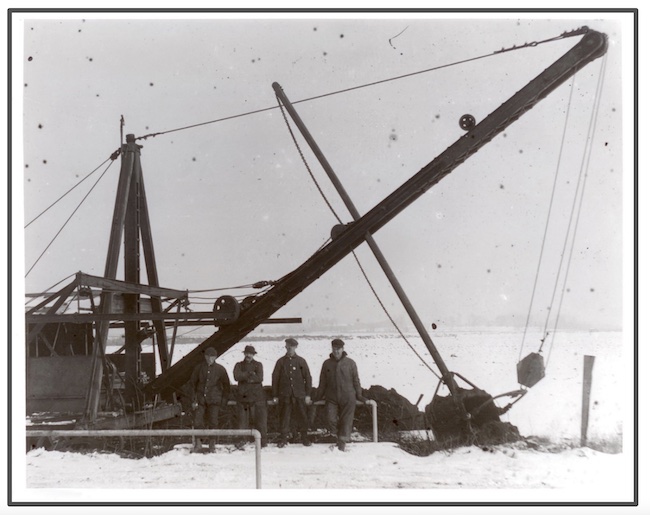

BARRE – The top photograph is not from an Antarctic expedition! The image from a glass negative shows a dredge excavating a main ditch on the swamp in 1913 for the Western New York Farms Company. Drainage was the first step in the formation of the mucklands.

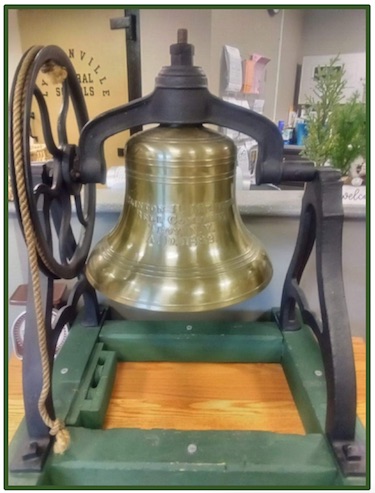

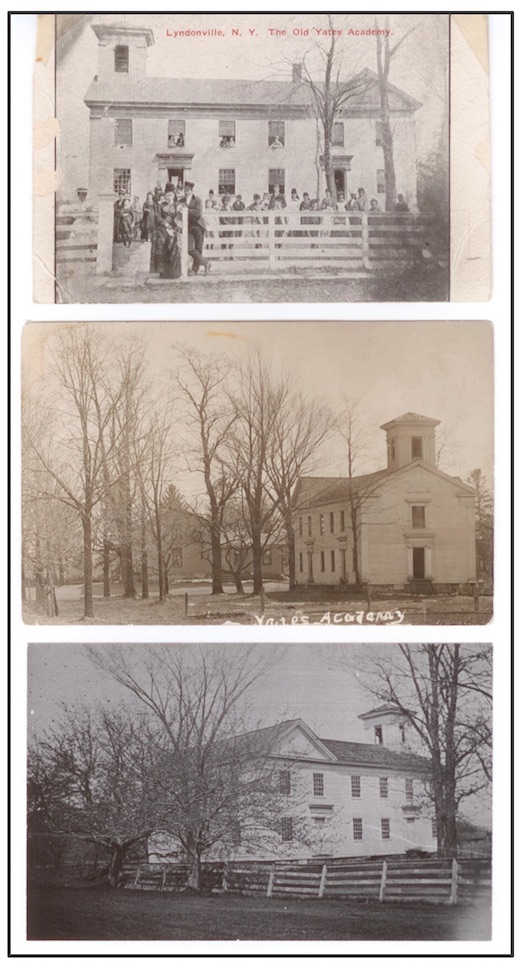

BARRE – The top photograph is not from an Antarctic expedition! The image from a glass negative shows a dredge excavating a main ditch on the swamp in 1913 for the Western New York Farms Company. Drainage was the first step in the formation of the mucklands. LYNDONVILLE – We continue our exploration of the history of the Town of Yates in anticipation of the upcoming Bicentennial celebrations.

LYNDONVILLE – We continue our exploration of the history of the Town of Yates in anticipation of the upcoming Bicentennial celebrations.