‘Good old days’ weren’t so good with sanitation

Privies could be conduits for spreading infectious diseases

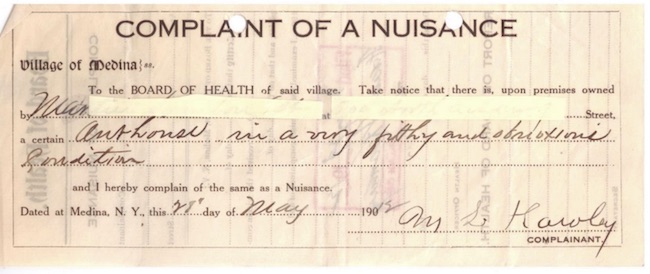

This is a ticket for a “complaint of nuisance in Medina more than a century ago. With these tickets the investigating officer would note observations on the reverse of the complaint docket. Typical observations might include: “found complaint justified” or “has connected with sewer”

By Catherine Cooper, Orleans County Historian

Illuminating Orleans, Vol. 1, No. 12

While farm outhouses had the advantage of space and could be relocated if necessary, conditions were more crowded in villages and cities. Municipal sanitation control was a significant issue as reflected in village ordinances.

Initially, the disposal of household wastes was the responsibility of the homeowner. Typically a nearby vacant lot or body of water would be used.

The earliest drains were installed primarily to accommodate rain storms and melting snow but also carried sewage. Odors were the main concern as the prevailing belief was that odors transmitted germs. The connection between contaminated water and diseases was not recognized until 1854 when John Snow, an English physician, carefully mapped cholera cases in London and narrowed the cause down to a contaminated well pump. In Buffalo, for example, outbreaks of typhoid and cholera persisted until discharges were routed south of the city’s water intakes.

Privies with vaults and leaching cesspools were an advancement, but they still had to be cleared periodically. The following references are to the Village of Medina, but the same patterns of development prevailed throughout the county.

The Board of Health Ordinance published the following in the Medina Tribune on July 2, 1874:

“No person shall have any privy upon any lot or premises within said corporation limits, without a vault under it at least four feet deep, and such vault shall be properly cleansed by using lime or other disinfecting substance therein.”

“No person shall be allowed to drain from any privy, vault, sink or cesspool in any street, alley or lane shall be properly secured by stone or other substantial covering.”

By 1893, these regulations were much stricter:

“No privy cesspool or reservoir into which any privy, stable or water-closets, sink or other receptacle of refuge or sewage is drained shall be constructed or maintained in any situation or in any manner whereby, through leakage or overflow of its contents, it may cause pollution of the soil near or about habitations, or of any well, spring or other source of water used for drinking or culinary purposes; nor shall the overflow from any such receptacle be permitted to discharge into any public place whereby danger to health may be caused.”

Furthermore, it was specified that receptacles of refuse or sewage were to be built of stone, the sides and bottom were to be tightly sealed with cement. A penalty of ten dollars a day ($267 currently, according to the Inflation Calculator) per day would be imposed for any violation.

The Board of Health was appointed annually by the Board of Trustees. According to the 1901 Charter and Ordinances of the Village of Medina, it was comprised of three members, with a “competent physician” as Health Officer. Practicing physicians were required to report any occurrences or pestilential or infectious diseases. The Board of Health had the power to publish ordinances. In addition, the Board had the power to regulate the height of water to be maintained in any race, stream, artificial water-course or feeder within the Village during the months of July, August and September and also to prescribe penalties for any violations of such.

The 1901 village Charter clearly outlined resident’s responsibilities with regard to

“Depositing putrid matter in the waterway” (five dollar fine for each offense),

“Throwing putrid matter upon sidewalk” (three dollar fine)

“Providing a convenient privy, at least three feet deep”

A comprehensive sewer system in the village was completed in 1893. Indoor plumbing was adopted gradually. There was some resistance to indoor plumbing at first, as the fear of sewer gases persisted, but plumbing improvements eliminated that problem. By 1908 the rates for household water charges included water-closets:

• Private house, 5 rooms: $5

• Each two additional rooms: .50c

• Bath tub in house: $2

• Water closet with house use: $4

• (Meter rates 50c per M gallons)

But, while domestic sanitation improved, the overall disposal system remained problematic as most municipal systems continued to discharge into local waterways for many years. The development of primary and secondary wastewater treatment plants took some time.

Return to the “Good Old Days”? No thanks!