Construction of Medina’s Masonic Temple began 100 years ago

By Catherine Cooper, Orleans County Historian

Illuminating Orleans, Vol. 3, No. 15

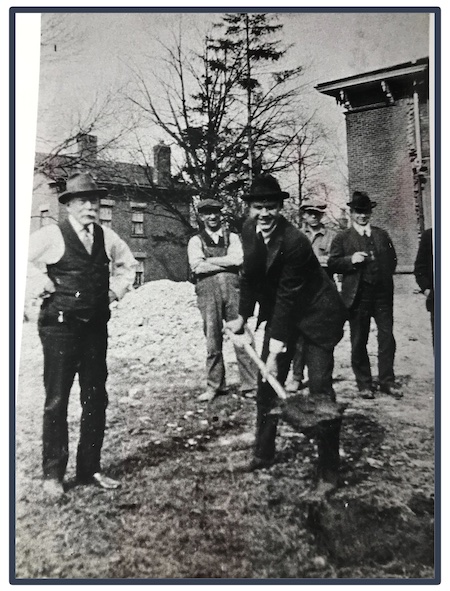

According to the Medina Daily Journal of April 30, 1923, he had just delivered a stirring address to the Masons assembled at the rear of the property, while standing on the stump of a tree which he and his father had set sixty years previously – in 1863. He had the honor of turning over the first spade of sod for the project.

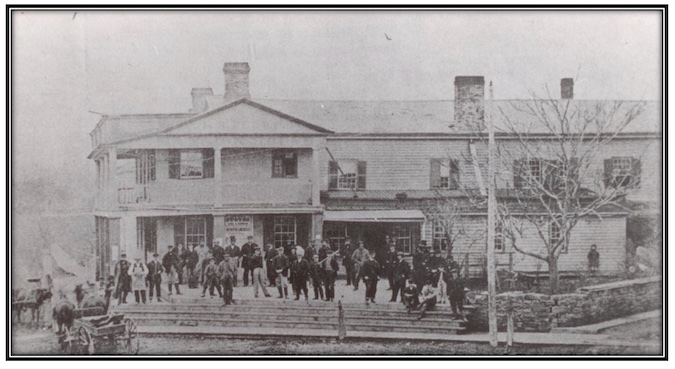

Chartered in 1854, the Medina Lodge No. 336, Free & Accepted Masons occupied several buildings in Medina. Their first meeting place was in the Fairman Building (345 N. Main, formerly NAPA Auto Parts). A fire in 1861 destroyed this building, their records and furnishings. Following several moves, the lodge relocated to Kearney’s Hall in the Proctor Building in 1877 (418 Main St., Knights of Columbus building).

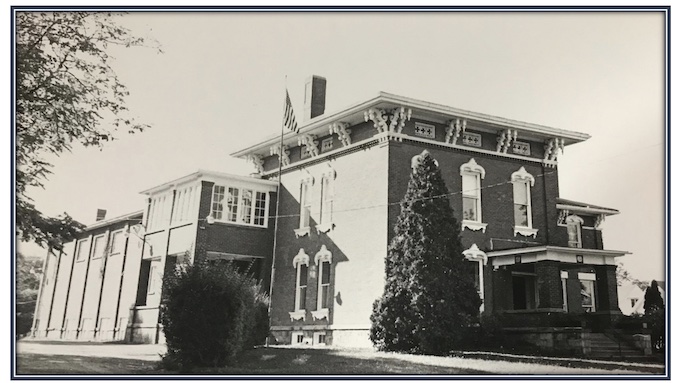

The lodge purchased the Italianate building at 414 West Ave. in 1921. Built in 1858, this had been the home of Arthur W. Newell, a dry goods merchant. Following the death of Mr. Newell and his wife Cornelia, in 1866, ownership of the home passed to their two sons, Myron and George.

They sold it to the Hon. Edward L. Pitts in 1877. Pitts was a lawyer and a member of the New York State Assembly from 1864 – 1868. At the age of 27, he was elected as Speaker of the Assembly, the youngest person to have held this office. A noted orator and parliamentarian, he was elected State Senator from 1881-83 and again from 1886-87. Hon. Pitts passed away in 1898, and his wife, Una (Stokes) died in 1920.

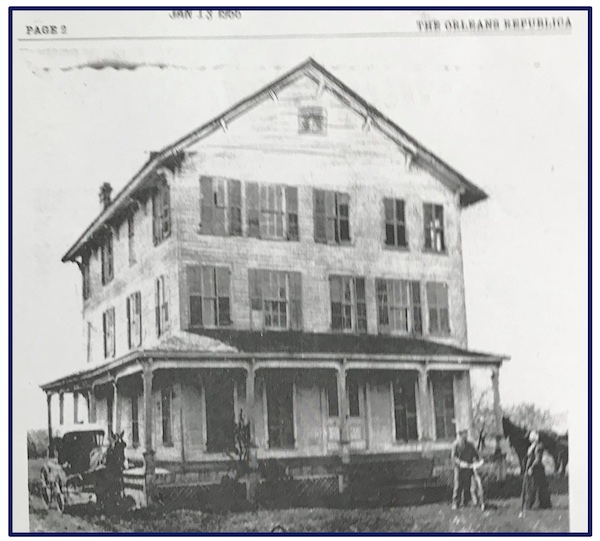

414 West Ave., Medina, showing the large addition to the rear of the building.

The Medina Lodge purchased the home in 1921. Desiring a space that suited their needs, they soon made plans to add a Masonic Temple. It was designed and constructed by Fred Mallison of Medina, who was also responsible for the construction of many of the local heritage buildings including the S.A. Cook Building on Main Street, City Hall, the Railroad Depot (currently Senior Citizen’s Center) and Medina Memorial Hospital.

The Temple featured a large lodge room with a pipe organ. Four distinctive stained-glass windows depicted Faith, Hope, Charity, and Music. A large dining hall in the basement accommodated 450 Masons at a celebratory dinner prepared “in a most able manner” by the Ladies of the Eastern Star. The dedication ceremony was conducted on April 30, 1925, by Most Worshipful Arthur S. Tompkins of Nyack, past Grand Master of the State of New York, under dispensation of Most Worshipful William A. Rowen, Grand Master.

Construction of the new Temple cost $136,000 ($2.4 million approximately today), which exceeded the $100,000 anticipated. Each of the 283 members had pledged in support of the project, in amounts ranging from $50 to $1,000. Contributions fell short which necessitated a loan of $60,000 ($1 million approximately today) from the Marine Trust Co. of Buffalo. Final payment on the mortgage was made in November 1960.

Citing declining membership and increasing costs, the Masons sold the building in 1982. It operated as the Islamic Center of Medina for some time and has been owned by the World Sufi Foundation since 2011.

ALBION – Emma B. Tripp became engaged to Louis J. Ives in 1908. They planned to be married in April 1911. But Mr. Ives disappeared.

ALBION – Emma B. Tripp became engaged to Louis J. Ives in 1908. They planned to be married in April 1911. But Mr. Ives disappeared.

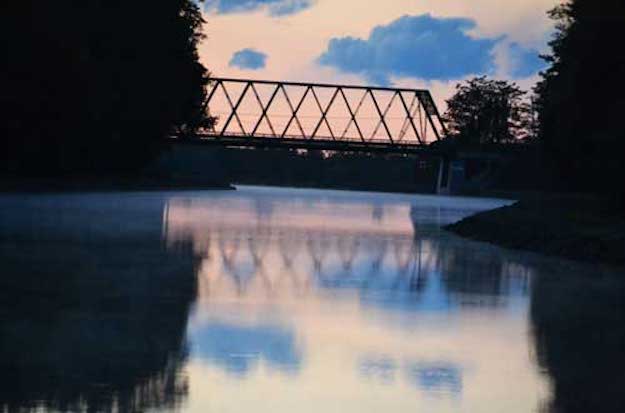

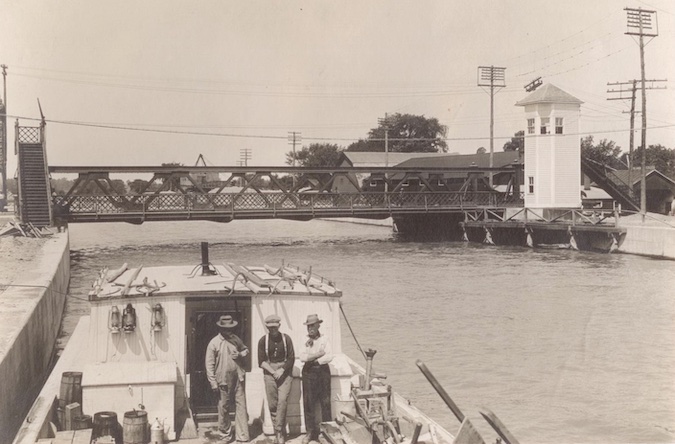

In Orleans County, which spans 24 miles across, twenty bridges facilitate north-south vehicular access across the Erie Canal. The Brown Road Bridge in Albion allows pedestrian access only. There is one stone arch tunnel at Culvert Road.

In Orleans County, which spans 24 miles across, twenty bridges facilitate north-south vehicular access across the Erie Canal. The Brown Road Bridge in Albion allows pedestrian access only. There is one stone arch tunnel at Culvert Road.

Reporting to the Orleans County Board of Supervisors in 1923, County Executive Nurse, Grace B. Gillette, reported 18 deaths due to tuberculosis in the county from October 1922 – October 1923.

Reporting to the Orleans County Board of Supervisors in 1923, County Executive Nurse, Grace B. Gillette, reported 18 deaths due to tuberculosis in the county from October 1922 – October 1923.