Contributions of pioneer women have largely been omitted in historical record

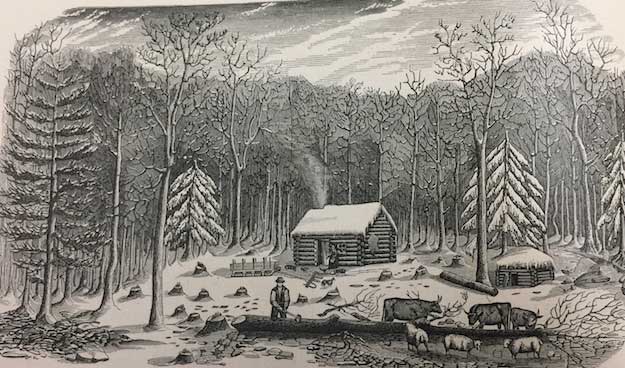

The Pioneer Homestead – Historical Album of Orleans County, New York

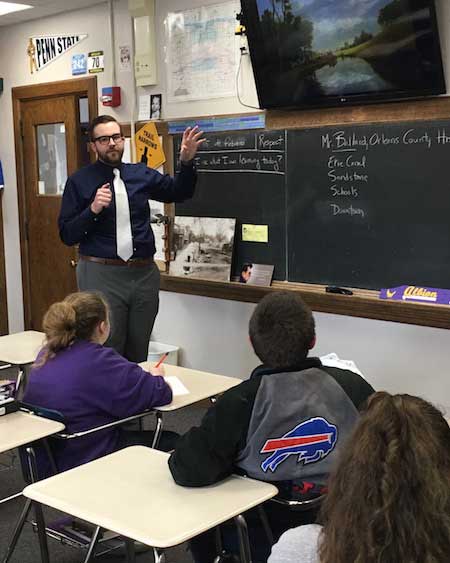

“Overlooked Orleans” – Vol. 4, No. 10

A question recently surfaced following my last article about Elizabeth Denio, one pertaining to the life of the pioneer settler Elizabeth Gilbert of Gaines. The question made me think about how women have appeared in the earliest recollections of our area’s history, if they make an appearance at all.

I was reading through Carol Kammen’s On Doing Local History and focused in on a common pitfall of local historians; trusting the published local historical narrative. What Kammen means by this is that we often fail to revise “what is held as truth.”

Much of our understanding of local history in Orleans County comes from the pages of Arad Thomas’ Pioneer History of Orleans County and Isaac Signor’s Landmarks of Orleans County, the second publication drawing from the chapters of Thomas’ publication. In these pages, the pioneer woman rarely makes an appearance and when she does her name is obscured by the significance of her husband. Elizabeth Gilbert is perhaps one of the exceptions.

On March 3, 1807, Elizabeth Gilbert purchased 123.5 acres of land approximately one mile east of Fairhaven in Gaines. It is Signor who references this land transaction, completely overlooked by Thomas over twenty years earlier which demonstrates the significance of Gilbert’s purchase of land at a time when men were more likely to conduct such business. As the story is told, Mr. Gilbert was known to suffer from fits of epilepsy and was discovered dead in “the road” in the middle of winter (the road presumed to be Ridge Road). With her niece, Amy Scott, Elizabeth cared for a yoke of oxen, cows, and young cattle over the winter before relocating to Canandaigua around 1811 or 1812.

Arad Thomas refers to Gilbert almost exclusively as “Widow Gilbert,” a woman defined by her marriage to her unnamed husband. In his description, she was a “hardy pioneer” who “cut down trees to furnish browse for a yoke of oxen and some other cattle…” When Noah Burgess and his family arrived at Stillwater in Carlton, he was unable to complete the trip across land to Gaines due to illness. It was “Widow Gilbert” who used her oxen to bring the family and their personal property to their new land along the Ridge Road. Mary “Polly” Crippen Burgess, Noah’s wife, who was described as a “strong, athletic woman,” proceeded to “chop down trees and cut logs for a log house” while “Mrs. Gilbert drew them to the spot with her oxen.” Men passing through assisted the women in raising the cabin walls.

Another notable story involves the wife of William McAllister, the first settler of what became the Village of Albion. Purchasing approximately 100 acres in 1810, McAllister constructed a log cabin in 1812 on a parcel of land where the County Clerk’s building now stands. Mrs. McAllister’s tenure in Orleans County was short as she died the same year the cabin was constructed. With no cut lumber for building a coffin and no clergyman to conduct a religious service, McAllister and other men constructed a makeshift box from roughhewn planks and wood spikes to bury the woman. To this day, Mrs. McAllister’s true identity remains a mystery.

While exploring these stories, I was drawn to one other mention of a very accomplished woman highlighted by Isaac Signor. He writes that Mr. Calvin G. Beach, the editor of the Orleans Republican, conducted his business with the assistance of his wife who, according to Signor, was “a woman of rare literary attainments, who was a contributor to many of the papers and magazines of that day.” Apparently her attainments were far from significant enough to mention her by name. Mrs. Juliette Hayward Beach was a noted poet and writer and was asked by Henry Clapp to review Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass manuscript. Literary critics have suggested that Walt Whitman wrote “Out of the Rolling Ocean, The Crowd” for Juliette, whose jealous husband prohibited her to write the poet.

As we delve deeper into the pages of local history, we must recognize that there are many more subjects and points of interest that remain untouched by the prying eyes of local historians. Sometimes, that research forces us to reconsider what we have come to hold true for so many years.

“Overlooked Orleans” – Volume 4, Issue 3

“Overlooked Orleans” – Volume 4, Issue 3

“Overlooked Orleans” – Volume 3, Issue 53

“Overlooked Orleans” – Volume 3, Issue 53