Historic Childs: Museum showcases artifacts from Horse and Buggy Days

By Doug Farley, Director Cobblestone Museum; and Bill Lattin, Retired Director

CHILDS – The impetus for this article surrounds this historic photo circa 1905 which Bill Lattin recently purchased at an antique shop. Notice here the set of steps used for mounting and dismounting a horse, wagon or buggy.

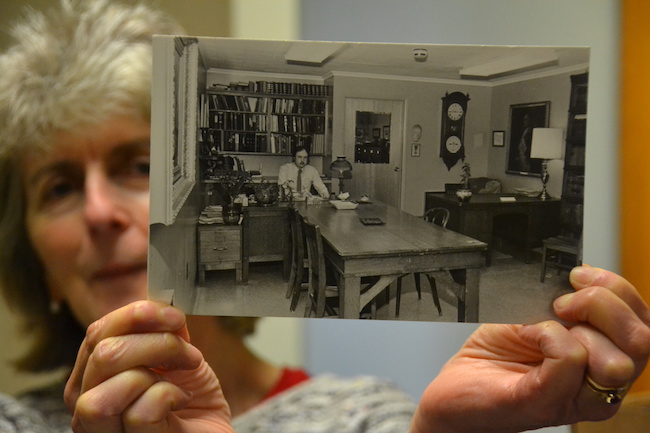

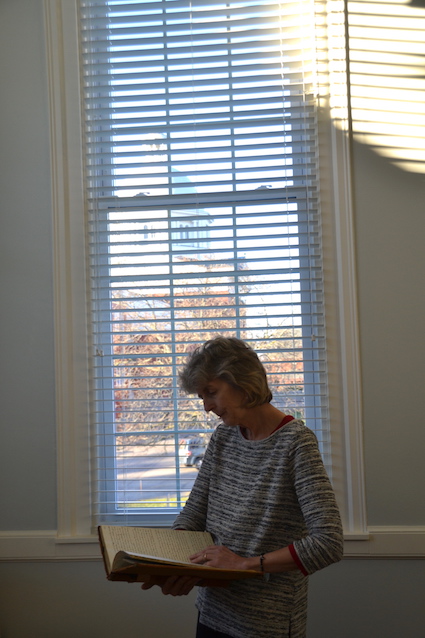

On the back of the photo is written Miss A. D. Reidel. The name of the presumed photographer, August Christe, is also stamped on the back with a rubber stamp. Retired Cobblestone Resource Center Director Dee Robinson researched these two names and found them in the 1900 U.S. Federal Census.

Annie Reidel was 14 years of age and living on Bessell Avenue in Buffalo. Albert Augustus Christie was age 33 and lived on Fifth Street, also in Buffalo. Through this little bit of detective work, we can guess this picture may have been taken in Erie County.

Notice again in this picture of the steps how the platform overhangs the base. This was done intentionally so the hub of the wheels on the democrat wagon, shown in the picture, could roll under the platform. This arrangement reduced the gap between the wagon box and the mounting steps. There had to be innumerable wooden mounting steps and platforms in use in the area in horse and buggy days.

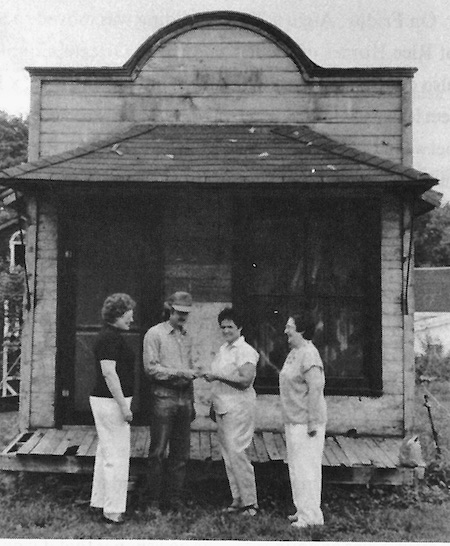

Using the historic photo as a guide, Bill Lattin recently built a replica set of mounting step, seen here in this modern photo, now located in front of the Vagg House in Childs.

The buggy in the photo was donated to the Cobblestone Museum by Bill, Tom and Mark Tillman in the 1980s when they renovated their old barn to become what is now the Carriage Room at the Village Inn Restaurant. The buggy is one of several historic vehicles that are planned for a new exhibit in the Vagg Carriage Barn located behind the Vagg House. Tours of the house and barn will begin in 2021.

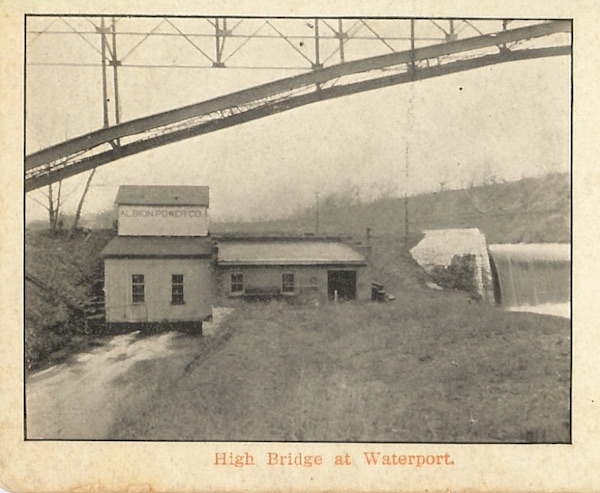

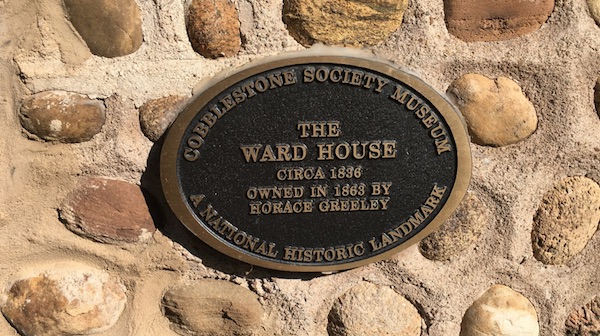

Also typical of the era, are the horse block or carriage stone seen here in front of the Ward House at the Cobblestone Museum. The large stone blocks had the advantage of not being easily moved and did not rot.

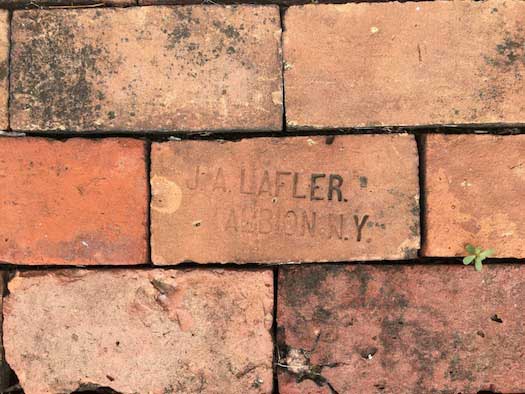

This piece of beautiful Medina Sandstone has the local family name “Bacon” carved into it. Bill Lattin recalls this horse block was given to the Museum around 1970 by Earl Harding. It was once located in front of the brick house at Five Corners. The Bacon horse block was moved to the Ward House about 1977 along with two fine Medina Sandstone hitching posts donated by former Orleans County Historian Cary Lattin. Each hitching post has the number 74 on it. Lattin said these came from 74 West State Street in Albion.

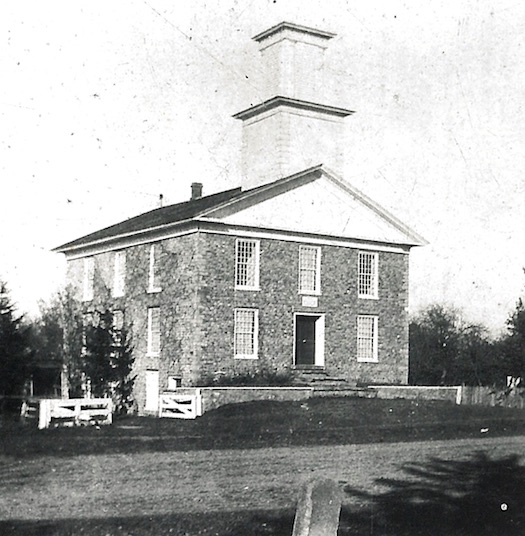

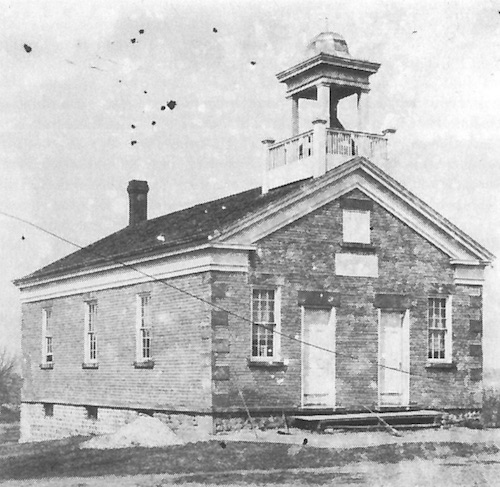

Because carriages and wagons were high off the ground it was advantageous to have a step, especially for ladies with long skirts, to embark and disembark such conveyances. This historic photo of the Cobblestone Universalist Church at Childs shows a high terrace in front for the same purpose.

It seems originally there was only a very high flight of wooden stairs up to the front entrance. In 1874 an earth ramp, brick platform and stone steps were added to the front of the church. This was so carriages on Sunday could pull right up in front and ladies and children could disembark on the level.

The driver of the buggy could then drive around to the carriage shed behind the church for the duration of the church service. Note a small portion of the shed shows on the left side of the photo behind the evergreens.

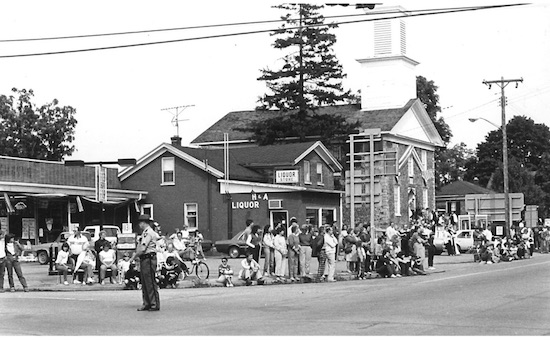

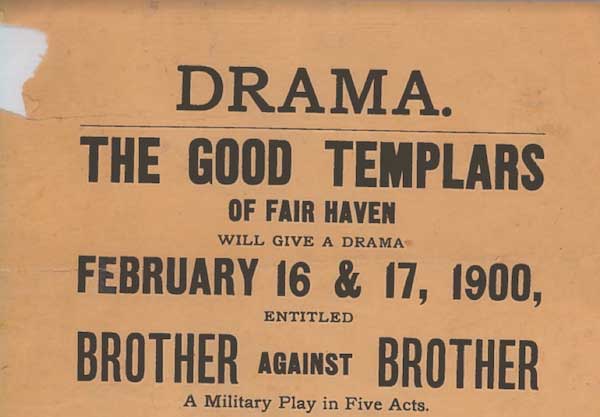

A similar situation existed at the Fair Haven Hotel, circa 1903, now the Village Inn at Childs. Notice the steps are at the corner. The rest of the porch is high across the front so carriages could pull right up close for people to easily step off onto the porch.

When carriage blocks were not in sight, the nearest stump often served as an easy way for the horse back rider to mount or dismount his steed.