Tonawanda Nation, environmentalists speak out against STAMP

Full buildout at 665 acres seen as threat to wildlife, Native American culture

ALABAMA – A full buildout on 665 acres of the STAMP manufacturing site in the town of Alabama, just south of Orleans County off Route 63, was called a threat to the culture of the Tonawanda Seneca Nation and the presence of wildlife, especially the short-eared owl and northern harrier.

Many speakers at a NYS Department of Environmental Conservation public hearing on Thursday evening were strongly against the DEC approving the plan proposed for mitigating the environmental impacts for the full build-out of the land. The Genesee County Economic Development Center is applying for the permit. About 200 people attended a 2 ½-hour public hearing at the Alabama Fire Hall.

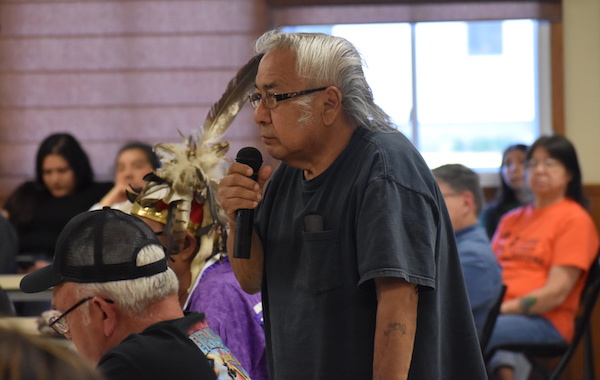

“We’ve been opposed to it from day one,” said Roger Hill, a Seneca Nation chief.

The site should be recognized as Seneca land at the local, state and federal levels, he said.

Scott Logan, a subchief for the Bear Clan, said the project would be a threat to birds, other wildlife, water, and the medicine plants in the Big Woods that border STAMP.

“This would be an immense injustice to Mother Earth,” he said at the hearing.

Valerie Parker-Campbell, a Tonawanda Seneca woman, said STAMP jeopardizes sacred medicines and practices of the community.

GCEDC has been applying for permits one project at a time and is instead pursuing a permit for the overall site. Its first tenant, Plug Power Inc., is under construction for a $290 million hydrogen production facility that is expected to be ready in the summer 2024.

Another company, Edwards Vacuum, announced plans in November for a $319 million factory that will produce equipment used in the semiconductor industry.

There is still plenty of space at STAMP for other businesses and GCEDC officials say they are talking with other companies about coming to STAMP.

But the location doesn’t fit a very rural area near the Tonawanda Indian Reservation and Iroquois National Wildlife Refuge, several speakers said. At full buildout the site could draw 600 trucks a day, likely leading to more motor vehicle accidents and more greenhouse emissions for the nearby residents, said Dr. Kirk Scirto, a family medicine specialist who works out of the Tonawanda Family Care Center on Bloomingdale’s Road in Akron.

He provides healthcare for many of the Tonawanda people, and said STAMP will have negative health consequences for the nearby residents. Emissions from cars and the manufacturing sites could exacerbate asthma, emphysema and other health conditions, he said.

He asked the DEC to deny the permit due to the health impacts on residents and also on the basis on environmental justice. The project will hurt the Tonawanda culture by scaring away wildlife. Many of the local residents rely on the lands for hunting and fishing, he said.

Chief Emerson Webster of the Tonawanda Band of the Senecas said the development at STAMP should be stopped because of the negative impacts on the local residents and Tonawanda people.

“We ought to work together to stop this,” said Chief Emerson Webster of the Tonawanda Band of the Senecas. “Our way of life is to save animals and medicine.”

He worries about the project’s impact on nearby lands that aren’t technically in STAMP, but would be altered by the project.

“We don’t need this,” he said at the hearing. “It’s not our way. This project may be good for some people, but it’s not good for us.”

Environmentalists decried a mitigation proposal from GCEDC. The full buildout would impact 665 acres of current open land. GCEDC is proposing for a 25-acre grassland habitat in the southeastern portion of STAMP and a 33-acre parcel north of the John White Management Area. That site would be converted from row crop to grassland.

GCEDC is seeking an Article 11 Part 182 permit for the mitigation plan, which would allow the agency to have 665 acres of land developed that is currently used as overwintering habitat for the state-listed endangered short eared owl and the state-listed threatened northern harrier.

Designating land of 25 and 33 acres doesn’t guarantee the endangered and threatened species will go to those sites, said Dr. Joe Stahlman, an anthropologist and research scientist at the University of Buffalo.

“The loss of birds and wildlife threatens the Tonawanda community,” he said.

The natural resources of a community are critical to the indigenous cultures, Stahlman said.

Kathy Melissa Smith, a member of the Tonawanda Band of the Senecas, lives a mile away from STAMP. She said the development of the site in such a rural area next to the reservation “will end our way of life.”

Environmentalists spoke at the hearing from the Buffalo Niagara Waterkeeper, Sierra Club, Save Ontario Shores, the SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry in Syracuse, University of Rochester, Western New York Environmental Alliance and the Clean Air Coalition of Western New York.

Pam Atwater, president of Save Ontario Shores, said the local area has about 10,000 acres that will disturbed due to wind turbine projects and large-scale solar. That land isn’t far from the wildlife refuge.

“The cumulative impact of those projects should be considered,” she said.

GCEDC has been successful convincing large companies to commit to STAMP, a “quiet site” with little ground vibrations that is critical to advanced manufacturing.

STAMP would have its own wastewater treatment facility on site, with the treated water to be released in Oak Orchard Creek.

That impact is a concern for Karen Jones of Shelby, who lives about 5 miles north of STAMP. She said the watershed is interconnected.

“The refuge wasn’t intended as a wastewater filtration system,” she said.

Margaux Valenti, attorney for the Buffalo Niagara Waterkeeper, said STAMP sits in an important area for biodiversity and the region’s ecological health.

“You’re setting this area up for disaster,” she said. “This is a grave threat to endangered species.”

Arthur Barnes, a Shelby resident, said the STAMP project is too disruptive to the Tonawanda community that relies upon and treasures open land and nature.

About 200 people filled the Alabama Fire Hall for the public hearing.

Scott Logan, a subchief for the Bear Clan, said STAMP is in a wildlife rich area. He said its development “would be an immense injustice to Mother Earth.”