Tax increases in past decade vary wildly among towns, villages

Carlton sees biggest jump in taxes, while Albion town is lone municipality to reduce them

Photo by Tom Rivers: Taxes in Carlton have increased at a faster rate than any town in Orleans County since 2007.

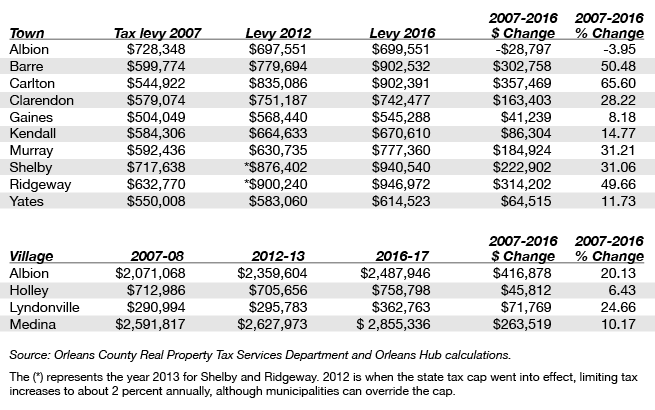

In the past decade, taxes in local towns and villages have increased at varying rates, with Carlton seeing the biggest jump – 65 percent since 2007 – while one municipality, the Town of Albion, has actually reduced taxes from 2007 to 2016.

The 10 towns collectively have increased taxes double the rate of the increase for the four villages from 2007 to 2016, according to an Orleans Hub analysis of tax levies for towns and villages.

The 10 towns collectively saw the tax levy, what the towns collect in property taxes, increased from $6,033,325 in 2007 to $7,742,244 in 2016. That $1,708,919 increase is up 28.3 percent in the nine years.

The four villages collectively went from $5,666,865 in 2007-08 to $6,464,843 in 2016-17, which is up $797,978 or 14.1 percent.

Carlton has seen the biggest tax increase since 2007, which the levy increasing by 65.6 percent, up $357,469 – from $544,922 in 2007 to $902,391 in 2016.

Gayle Ashbery, the town supervisor, said today she was aware of recent increases. She noted the town has wrestled with a re-evaluation of 2,400 properties in Carlton. It paid GAR Associates Inc. $68,000 to compile the data, visiting every property in the town and make note of swimming pools, additions, sheds, garages and exterior property improvements. That project, begun in 2014, was done to make sure Carlton had up to date assessment records following an outcry from residents in 2013 over reassessments that many residents said were too high.

One town actually collected less in taxes in 2016 compared to 2007. Albion’s town tax levy dropped 4 percent in the nine years, down nearly $30,000 from $728,348 in 2007 to $699,551 in 2016.

“You can do it but it takes some work,” said Matt Passarell, the town supervisor.

The towns face escalating health insurance and employee benefits costs, he said, “and every one wants a raise.”

Albion has looked for efficiencies, sharing a codes officer with Gaines, for example, Passarell said.

“You have to be creative,” he said.

The town has dipped into fund balances in recent years to help stave off tax increases. Passarell said grants are also helping to tackle infrastructure projects.

The town also has seen a little boost in sales tax revenue. The county shares $1,366,671 in sales tax each year collectively with the four villages and 10 towns. The town and village total has been frozen since 2001.

However, the amounts can vary for each village and towns with villages. If the town’s assessments grow faster than the villages’, the towns will get more sales tax, taking away some of the villages. That’s what has happened in Albion. The town-wide assessments have outpaced the village assessments. That has resulted in the town sales tax share growing from $111,754 in 2013 to $124,978 in 2017. The Albion village share has fallen from $180,457 in 2013 to $164,617 in 2017.

Tax cap introduced in 2012

The governor and State Legislature approved a tax cap in 2011. That took effect in 2012 and tries to limit tax increases to 2 percent annually, although the threshold can change each year and municipalities can override the cap.

The cap seems to have slowed tax increases in the towns since 2012. Clarendon, for example, raised taxes $172,113 or 29.7 percent from 2007 to 2012, but has actually cut taxes since then. Gaines also has reduced taxes since the cap was implemented, and other towns have slowed the growth in taxes since 2012.

Ridgeway, for example, raised taxes $267,470 or by 42.3 percent from 2007 to 2013. The three years after, Ridgeway increased taxes by $46,732 or 5.2 percent.

(Three of the four villages had tiny tax increases from 2007 to 2012 – Holley actually lowered taxes during those five years. Albion and Medina both eliminated their village courts which saved some costs, with the expense passed to the towns. The villages’ taxes have increased since the tax cap, some years exceeding the 2 percent threshold.)

Villages slow tax increases, but suffer from shrinking assessments

Among the villages, none raised their taxes more than 25 percent over the nine years. Six of the 10 towns saw increases above 25 percent.

Holley had the smallest increase at 6.43 percent. However, the village separated the fire department from the village budget. The fire department is now in a separate tax.

The town tax increases may not be as noticeable each year because the towns’ assessed values are increasing, giving a bigger tax base to absorb the larger tax levies. That means the tax rates are often the same or see small increases. Many of the local elected officials judge their budgets on how the tax rate changes, and don’t fret as much about the tax levy.

However, a stable tax rate for larger assessed values still results in bigger tax bills for property owners (if their assessments go up.)

The villages are facing shrinking assessed values, so many of the Village Boards in recent years have reduced village staff and projects, preventing big increases in the tax levy. However, because the assessed values are going down, often the tax rate still goes up.

In Lyndonville, for example, the tax rate has climbed from $9.70 per $1,000 of assessed property in 2008-09 to $13.65 in 2016-17. That is a 40.7 percent increase over eight years. Village officials say it’s difficult to prevent property tax increases when sales tax and mortgage tax revenues are declining.