Stress debriefing team meets with firefighters after response for man who drowned

‘My message to them is they didn’t cause the harm. They did nothing wrong. They did the best they could.’

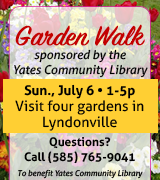

Photos by Tom Rivers: Firefighters from the Albion Fire Department, right, and Medina Fire Department search the water in a former quarry on the night of April 23. Ryan J. Perkins, 30, of Canal Road drowned trying to rescue a dog.

MURRAY – There were about 50 firefighters working on the night of April 23, trying to locate a 30-year-old Murray man who went into the chilly water of a former quarry in search of a dog.

The man drowned. He was found after a 2 ½-hour search with firefighters in four rescue boats. Other firefighters were along the shoreline.

For many of the firefighters it was the first time they had responded to a fatal call. They went to the scene expecting it to be a rescue, but it changed to a recovery.

Harris Reed, the fire chief for the Murray Joint Fire District, recognized there were many young firefighters on the call and they might be struggling to cope when someone close to their own age did not survive.

“This was the first fatality for many of the new members,” Reed said. “It can be very difficult for new members.”

Orleans County has had a stress debriefing team for firefighters for about 15 years. Mental health professionals are part of the team. Firefighters Tim Fearby of Shelby and Guy Scribner have been co-leaders of the group since it started.

Fire chiefs can request the team if they sense firefighters would benefit in talking through how they’re feeling and also hearing from other firefighters struggling with their emotions. The stress debriefing team might be called after a fatal car accident, fire, drowning or an emergency medical response with a child who doesn’t survive.

Reed said in those incidents where someone dies, firefighters will feel guilt that they may not have done enough, or if they had responded differently the person may have lived.

“My message to them is they didn’t cause the harm,” Reed said. “They did nothing wrong. They did the best they could.”

Reed has been a firefighter for about 25 years. When he started and there has a difficult call with a fatality, firefighters didn’t really talk about it.

“Years ago you came back to fire house and just went home,” he said.

But fire chiefs and the veteran firefighters know better now about the mental health toll of responding to those calls.

“Our people here come first,” Reed said. “Everyone responds to a situation differently. But I wanted to open up (the stress debriefing) to everybody who was at the incident.”

Murray Joint Fire District Chief Harris Reed, left, and Justin Niederhofer, deputy director of the Orleans County Emergency Management Office, set up a command post during on April 23 during a response for a man in the water. He was found after a 2 ½ hour search.

Danielle Figura, director of the Orleans County Mental Health Department, is trained in leading the critical incident stress management. They are usually done within 72 hours of the incident.

The stress debriefing in this case was last Monday on April 26, three days after the drowning. Figura and the team met with 12 firefighters at Fancher-Hulberton-Murray fire station. That included firefighters from Murray, Albion and the western battalion.

It is a peer-driven response where the group will often replay the scenario with “what if.” No one takes any notes and people are encouraged to share.

“It is a safe space where there is no judgement,” Figura said.

‘First responders are human first. They are hearing from others with similar reactions which helps validate how they are feeling.’

Figura said it is very helpful to firefighters to articulate how they are struggling and to know others are feeling a similar way.

“They are hearing from others with similar reactions which helps validate how they are feeling,” she said.

Volunteer firefighters often go from being at work or at home to a scene a few minutes later where a person they know has been killed in an accident.

“First responders are human first,” Figura said. “They need to take care of themselves.”

While mental health still has a stigma, especially among first responders, Figura said she is encouraged the critical incident stress management team is called more frequently. That shows her the team is being successful in helping the first responders process some difficult emotions.

“Twenty years ago this wasn’t very well accepted,” she said. “But we’re seeing this push as first responders hope to grow and recruit more to stay in that role.”

Most of the stress debriefings are about 60 to 90 minutes, and Figura and the team members can direct the first responders to additional help if needed.