Sears, Roebuck catalogs changed retail a century ago

By Catherine Cooper, Orleans County Historian

“Illuminating Orleans” – Vol. 2, No. 4

Yes, you guessed it: Sears, Roebuck and Co.!

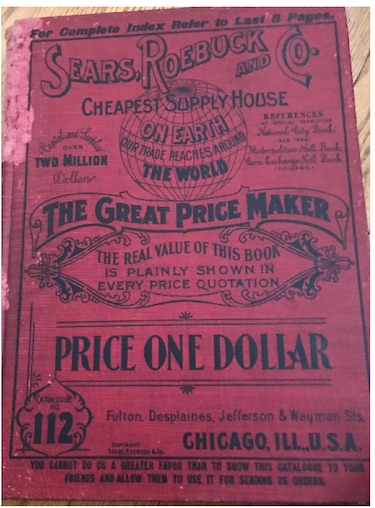

A Sears, Roebuck catalog from 1902 was recently donated to the Orleans County History Department. The catalog highlights the similarities between Sears, Roebuck and Amazon.

Sears started in 1886, selling watches by mail-order, then a new purchasing method. In 1994, Amazon began selling books online, also a new concept. In both instances, the combination of energetic leadership, fortuitous timing and a particular combination of socio-economic and demographic factors facilitated their explosive growth and market dominance.

Richard Sears and Alvah Roebuck issued their first catalog, 322 pages in 1891. At that time, 65% of the population lived in rural areas and were required to travel to often distant post boxes to pick up their mail, or to pay carriers for delivery.

The Rural Free Delivery Act was passed in 1894 to provide mail delivery, free of charge, to all. Naturally, the legislation had encountered the opposition of the paid carriers and of the store owners who rightly feared the prospect of mail-order shopping.

The Sears catalog which has been donated to the History Dept. is a hefty tome, 1,208 pages, offering every item imaginable. All the items are listed in the eight-page index, from Abdominal Belts to Zitho Harps.

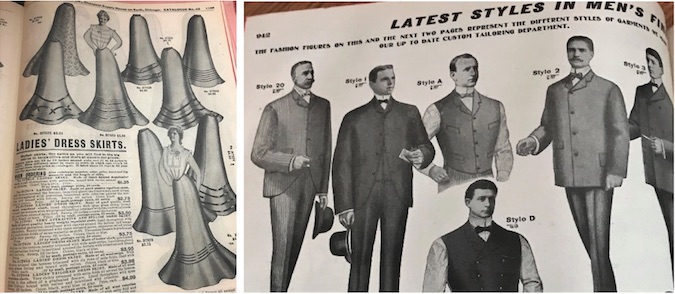

The catalog included a comprehensive range of dress and work clothing for the entire family

Suddenly, the floodgates of consumerism were open, everyone could buy anything, conveniently and privately. Thanks to Sears’ inspired privacy policy, people could shop “incognito” as the company vowed that every transaction would be strictly confidential, that their name and address would not appear on any article of merchandise. One can well imagine that this would have been appreciated especially by customers in small communities.

The catalog is printed in black and white, but carpet, floor linoleum and oilcloth patterns were shown in color.

This was not a free catalog – the cloth bound edition cost $1, and the paperback edition 50 cents. These prices may seem inexpensive to us, but at the time, one could purchase one pair of men’s very best quality German knit socks for 40 cents and three pairs for $1.20.

Sears’ justification for the charge was very logical: the cost of sending free catalogs to everybody was a waste of paper and money, and a cost which was passed on to the customer. Providing the catalog only to those who intended to buy reduced waste and cost and ultimately benefitted the customer. Unfortunately, paper and money are still being wasted on the mailing of multiple copies of unsolicited magazines.

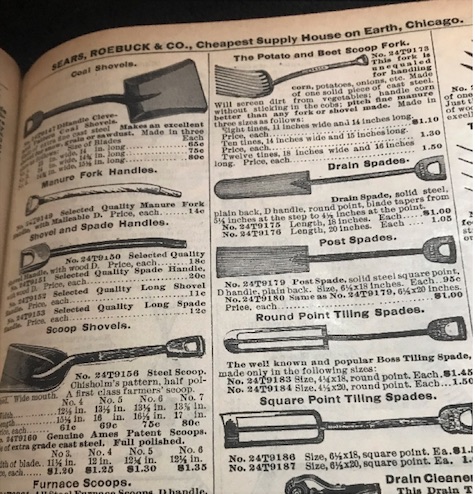

Spades, shovels and tools for every task.

The Sears catalog provides an insight into the daily life of the era, the items that people wore and worked with, the items that surrounded them in their homes: furniture, kitchen items, guns, musical instruments, horse tackle, door locks, heating stoves, clothing, footwear. Then, there are the more unexpected items: tents, power windmills, ploughs, tombstones.

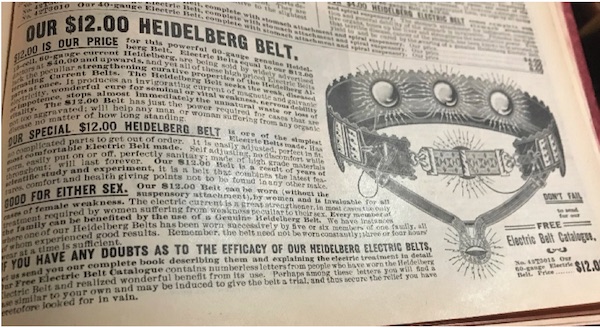

Every page of this catalog is a fascination – the descriptions, the terminology that would be unacceptable today: “underwear for fat men,” the outrageous items, and the outrageous claims:

“WHITE STAR SECRET LIQUOR CURE:

Makes them stop drinking forever.

Drunkards cured without their knowledge.”

The 60-gauge current Heidelberg Belt “seeks the weak, diseased parts at once…cures vital weakness, nervous debility or impotence”

From a historian’s point of view, the catalog is an invaluable resource to help identify items, since so many are no longer familiar to us. It can also be used to help date photographs by comparing clothing and background items.

This 120-year-old catalog is in remarkably good condition. It was originally owned by Herbert C. Hill of Shelby. A printing press which he operated was previously donated to the Cobblestone Museum. We thank the Hill family for their generosity.