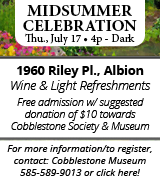

Rural cemeteries deserve our attention, too

Photo by Matthew Ballard: Grave of William & Ruth Tanner – Tanner Cemetery, Albion, New York

“Overlooked Orleans” – Vol. 4, No. 22

I spent some time over Memorial Day weekend photographing historic markers and cemeteries as part of an ongoing inventory project I am working on. I was amazed at the beauty of our little burial grounds scattered throughout the county; there is definitely something to be said about the peacefulness of eternal rest and the aura that exists within the cemeteries.

Unfortunately, over the years many of our rural cemeteries have fallen victim to Mother Nature, or worse, vandals. In 2006, two cemeteries in Clarendon were attacked by mischievous kids who knocked over stones and smashed others with sledgehammers. In 2012, vandals were active at Beechwood Cemetery in Kendall, tipping over several dozen stones. A lack of respect and appreciation for our past often fuels this type of behavior.

I have received a number of inquiries over the past several months about some of the smaller cemeteries in our area including the Billings Farm Cemetery on Baker Road in Carlton and the Long Farm Cemetery on Rt. 31 in Albion near Transit Road. In the case of the latter, many of the graves are marked by fieldstones and masked by overgrowth and thickets. The question I most often hear is “why?” Why are these cemeteries allowed to fall into a state of disrepair? Time, money, and no descendants are often the reasons, but are these smaller grounds not just as important as our larger cemeteries?

I stumbled across an article written by Bill Lattin a number of years ago, an article drawn from one written by his father Cary Lattin in relation to the old Annis Cemetery on Rich’s Corners Road in Albion. In 1907, Sophia Harling Lattin visited the cemetery where her grandparents were buried, only to find that the grounds were overgrown with briars, locust, and myrtle. She found the condition to be quite shameful, overcome by disappointment that sacred ground should be allowed to fall into such a state of disrepair. Refusing to be deterred, she trudged through the thicket and gathered the names of the deceased from the tombstones in order to assemble a battalion of workers to clear the dense brush.

Upon the completion of this herculean task, the Town of Albion was encouraged to mow the cemetery from that point forward. Lattin paid $10 to have a wrought-iron gate and posts installed at the front of the cemetery, which still stands with a small wooden placard that reads “Annis Cemetery” (albeit in poor condition). Within this cemetery stands a small monument to the memory of Jonathan Rich, a member of Capt. Ebenezer Mason’s Company of Minute Men who responded to the Lexington Alarm on April 19, 1775; the quintessential Patriot.

Another example of community-driven efforts to resurrect the sacred space of our rural cemeteries is Tanner Cemetery, situated across the road from Mount Albion Cemetery. I am often asked about the origins of this particular burial ground given its close proximity to the much larger municipal cemetery. It appears that the cemetery, “established” in 1833 started as early as 1825 with the burial of Ruth Tanner, wife of William Tanner (1751-1831). The couple was interred on the farm owned by their son, Samuel Northrop Tanner, who is buried atop a hill east of the main gate in Mount Albion Cemetery. On numerous occasions, this cemetery became overgrown by weeds, vines, and small trees and on each occasion was cleared by volunteers. Over the years, stones were knocked over and broken with the occasional passerby leaning the stray markers against trees. Small unmarked rocks are situated throughout the burial ground, likely marking the graves of those who could not afford an etched stone.

Records indicate that William Tanner was paid 9 pounds in March of 1781 for service as a private with the 9th Regiment of Foot, U.S. Service with Col. Crary commanding. Those same records indicate that he was wounded during his service and carried a scar for the remainder of his life. Also buried on this site is Sgt. Jedidiah Phelps, a member of the Connecticut Militia and silversmith by trade. After his relocation to Barre in 1819 (then part of Genesee County), he played an active role in establishing the First Presbyterian Church at Albion.