Norwegian ‘Slooper’ from Kendall persevered and made mark as engineer in NYC

“Overlooked Orleans” – Vol. 6, No. 19

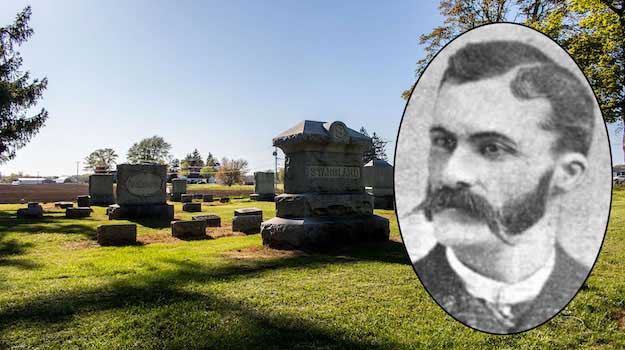

KENDALL – This photograph shows the Stangland family burial plot at Greenwood Cemetery in Kendall. The cemetery is the final resting place for Benjamin Franklin and Emily Bridgeman Stangland. Born on January 20, 1848 in Noble County, Indiana, “Frank” was the son of Andreas Stangland, a Norwegian immigrant, and Susan Cary of Kendall.

Frank’s father arrived in the United States in early 1825 to prepare land in Kendall for the arrival of 52 immigrants from Stavangar, Norway. Docking at the Port of New York on October 25, 1825, the “Sloopers” as they were called travelled along the Erie Canal to Holley, where they embarked for the shore of Lake Ontario. Andreas was a bachelor and settled on a small parcel of land situated north of the Lakeshore and Norway Road intersection. Family lore says that while exploring his property, Andreas stumbled upon the home of John Cary where he met his future wife. Unable to speak English, he received lessons from Susan who was a teaching in a nearby schoolhouse.

Andreas and Susan had five children in Kendall including Eleazer, Lydia, Tallock, Bela, and Rosetta. Around 1839, a wealthy farmer from Indiana named Ole Orsland visited Andreas and offered to trade 600 acres of land in Indiana and $200 for Stangland’s 48 acres in Kendall. Believing Orsland to be a trustworthy man and presented with an unbelievable opportunity, Stangland accepted the offer much to the disapproval of his wife. When the Stanglands arrived in Indiana, they found that less than 25% of the land was tillable and the majority of the acreage was a swampy mess. The young couple welcomed four more children to the family while in Indiana; Maria, Andrew Jackson “Jack,” Mary Elizabeth “Libbie,” and Benjamin Franklin “Frank.”

The swampland would take its toll on the Stangland family, as Rosetta (my 5th great grandmother) developed “swamp fever” every year and was forced to spend time with her grandparents in Kendall to recuperate. While Andreas spent most of his time trying to drain his farm, he contracted pneumonia and died August 31, 1847, nearly five months before the birth of Frank. Susan suffered immensely following the passing of her husband and was said to have died of a broken heart on November 4, 1848. Frank was sent to the home of a Mrs. Squire Young to be nursed over the winter while the children awaited the arrival of their grandfather from Kendall.

At the Cary Farm in Kendall, Frank’s uncle Richard Cary offered to adopt his young nephew. Instead, his uncle Alex Cary picked him up and said, “Mother, I think we will keep Frank,” and left the room. From that point forward, Frank remained on the farm, becoming a full-fledged farm hand by the age of fourteen. After his grandfather died, he would take wheat to Kendall Mills so it could be ground into flour.

Frank attended the one-room schoolhouse at the corner of Norway and Lakeshore Road, where his mother taught his father how to read and speak English. Wishing to continue his scholarly pursuits, Frank attended the Brockport Normal School at the age of sixteen before moving to Indiana to live with his brother, Tallock. It became apparent rather quickly that Frank was not cut out for the farm life. He returned to the Cary Farm in Kendall before traveling to Rochester to commence studies in business at Bryant & Stratton & Co.

Fresh out of business school, Frank applied to work as a shipping clerk at Forsyth Scales in Rochester. Preferring sales to clerking, the firm sent him on the road which led him to Chicago in 1870. On October 9, 1870, that city suffered the massive conflagration known as the Great Chicago Fire. Asleep in his bed, two neighborhood boys alerted Frank to a massive fire on the city’s southside. He sprung out of bed and rushed to the store where he “watered” the store’s wooden back platform.

As the fire spread and nearby clerks fled, Frank rushed into the store, opened the safe, and loaded the company’s financial ledgers into a trunk. He tied to the trunk to a handcart and spent the better part of the night pulling the cart across the city. Having located his boss, Mr. Forsyth said, “You needn’t have taken the trouble to take the books out Frank, for you know we made that safe and it is perfectly safe.” Six weeks later, they dug the safe out from the ruins only to find that the remaining documents within the safe were turned to dust.

During his time in Chicago, Frank kept in touch with his sweetheart back home, Emily Sedgwick Bridgeman. Her parents were quite skeptical of a “prosperous looking young man who traveled,” so the couple settled on a ten-year “understanding” rather than a traditional engagement. They wed on October 25, 1876.

During his time with Forsyth, Frank developed a process of counting small watch parts by weighing them on delicate scales. Shortly after his marriage, Frank and Emily relocated to New York City where Frank commenced work as a mechanical engineer with Howard & Morse. He quickly became an expert on ventilation and drying ovens, installing ventilator systems in some of the largest buildings in the United States.

The Stanglands owned a summer home on Rt. 18 near Kendall and upon Frank’s retirement in 1932, he and Emily made the house their permanent residence. He died July 31, 1941 at the age of 92 and was interred in this lot in Kendall.

Of the many interesting anecdotes relating to Frank Stangland, perhaps none is as interesting as his participation in a major New York City murder trial. In 1890, Carlyle Harris, a medical school student at the New York College of Physicians and Surgeons gave his wife Helen Potts a lethal dose of morphine placed in capsules. Frank was one of twelve “well-educated” jurors that sat for the trial. Carlyle was found guilty and sentenced to death, which was carried out in 1893 in Sing Sing’s electric chair.