Legacy of Carl Akeley, famed naturalist from Clarendon, threatened by oil drilling in Congo

“Overlooked Orleans” – Vol. 4, No. 27

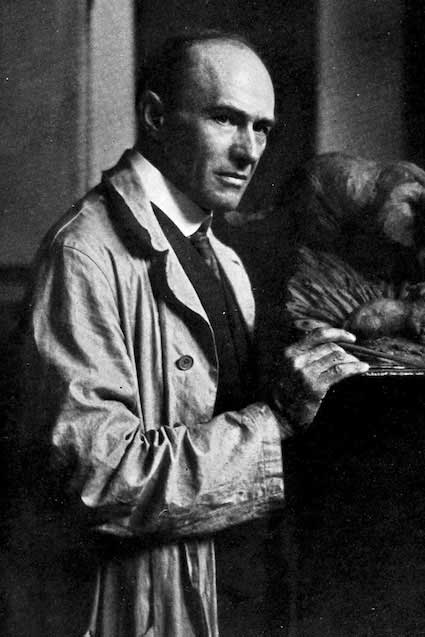

Carl E. Akeley, circa 1914, The American Museum Journal

The story of Carl Ethan Akeley is one of my favorite tales of a local boy who traveled beyond the boundaries of Orleans County to leave a lasting impact on the world. This prolific naturalist, taxidermist, artist, and inventor was born May 19, 1864 to Daniel Webster Akeley and Julia Glidden.

He grew up as a child in the family home on Hinds Road where he took an early interest in the preservation of animal specimens. To his family, this “morbid curiosity” earned him the reputation of being “odd,” that was until he mounted his aunt’s beloved yellow canary that died one cold evening.

He entered the tutelage of David Bruce of Sweden, New York, an artist and taxidermist known locally for his mounting of bird specimens for E. Kirke Hart (now on display at the Cobblestone Museum). Akeley’s time with Bruce was short, the latter recognizing his pupil’s unusual proficiency and skill in the art of taxidermy. At the age of 19, Akeley found employment with Ward’s Natural Science Establishment in Rochester, officially launching his professional career in mounting animal specimens.

It was during his tenure at Ward’s that he became attuned to the disconnection between taxidermy as an art and taxidermy as a science. To Akeley, these mounted specimens lacked the context that came from showing animals in their natural habitats. Although he held strong feelings on the direction of the profession, it was not until his work on the mounting of Jumbo, P.T. Barnum’s East African circus elephant in September of 1885, that he developed an expert’s voice.

Two years after his first major project, he left Ward’s for a part-time position with the Milwaukee Public Museum where he developed his trademark of setting animals against painted backgrounds. These backgrounds mimicked the natural habitat of the focal specimen, adding the necessary context to the piece. It was this particular type of work that earned Akeley his reputation as a premier taxidermist and eventually led to his appointment as chief of the department of taxidermy at the Field Columbian Museum (now the Field Museum) in Chicago. During his tenure in Chicago, Akeley experienced his first of five African expeditions. It was on this trip that he first stared death in the face, killing a leopard with his bare hands.

Over the course of his life, Akeley was responsible for the invention of a “cement gun” used for spraying plaster under newly mounted animal skins. The device was used in the repair of the exterior walls of the Field Museum and earned him the John Scott Legacy Medal of the Franklin Institute in 1916. It was thanks to Akeley’s work that we have motion picture footage of the First World War. His 1916 patent of the Akeley Motion Picture Camera, dubbed the “pancake camera,” was developed out of his efforts to capture moving images of animals in the wild. The U.S. War Department adopted the camera for capturing war footage, which later received the John Price Wetherill Medal of the Franklin Institute in 1926.

Much more can be said of Akeley’s life; his commitment to the American Museum of Natural History in New York City, his insistence on shooting animals for the sake of preservation instead of sport, his friendship with Theodore Roosevelt, or his numerous encounters with death while on expeditions in Africa. His lasting legacy, however, is defined by the establishment of the Albert National Park in Africa. In 1921, he visited Mt. Mikeno on his fourth expedition to collect gorilla specimens. It was during this visit that his ideas on the collection and preservation of animal specimens fundamentally changed. Thanks in part to Akeley’s work, King Albert I of Belgium set aside land for the first national park in Africa in 1925. That park remains intact today as the Virunga National Park.

This UNESCO World Heritage Site is home to the bush elephant, the endangered bonobo, and Akeley’s endangered mountain gorilla. News media announced recently that the Democratic Republic of Congo is now exploring the possibility of opening this important refuge to oil drilling. With this news comes the possibility that Akeley’s legacy could come to an end in our lifetime. It was thanks to his foresight that we can view these beautiful animals in a recreation of their natural habitat. It was his lifelong vision that we should never lose the ability to view these living species in the wild, if we should so choose.