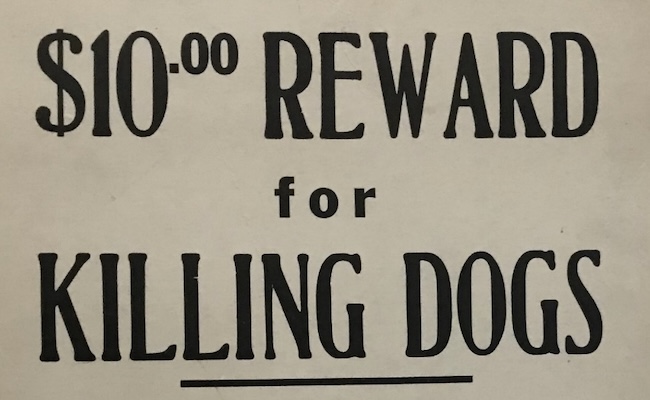

In 1940s, Sheriff put out edict to kill ‘worrying’ dogs that were attacking sheep and poultry

By Catherine Cooper, Orleans County Historian

“Illuminating Orleans” – Volume 4, Number 26

Many of these incidents were reported in the local newspapers: over the course of four days in May 1944, over $1,000 worth of sheep were destroyed by dogs in the Town of Barre: 25 at the Frank Hedges farm, 20 at the Clarence Houghton farm, and 10 at the Martin Brown farm.

Dogs were reported to have been molesting a flock belonging to former Sheriff Sidney Treble. The Sheriff’s dept. destroyed four dogs, two while the dogs were still attacking a flock. In June 1944, 135 chickens owned by Nunzio Spalla, north of Albion, were killed by dogs. He managed to shoot the larger attacking dog but missed the other.

Even the most adorable household canine pets can turn vicious when they are among a flock of timid, scurrying sheep, who, lacking horns, venom, sting, bite or heft, are singularly defenseless animals.

It is widely acknowledged that a dog who has attacked sheep once will attack them again. The term “worrying” has been used for this molestation. It aptly describes the effect of an attack on the flock, and on the farmer concerned for the future safety of his investment. In addition to the financial loss inflicted by an attack, there is the more dismaying problem of dealing with the gory cleanup of the destruction.

Sheep raising was lucrative in the 1940s, as the war had increased demand for wool for the manufacture of uniforms and blankets. Many Orleans County farmers owned sheep; some flocks were as large as 800.

Each Town was responsible for the payment of damages caused by dogs whose owners could not be identified. The County Treasurer reported annually to the Board of Supervisors on the claims paid for damage done by dogs: in 1944 this totaled $4,126.30 and $4,639.95 in 1945. It is not surprising that attempts were made to reduce these costs.

The Sheriff asked for the addition of a full-time deputy to act as a dog warden for the county. He believed that this was the most effective way to cope with the problem of dogs running loose at night and attacking sheep. In 1943, the Board of Supervisors authorized the appointment of this special officer, to operate under the sheriff’s office, at an annual salary of no more than $2,000.

In 1949, the County Treasurer reported that the amount paid by the County for damages done by dogs was $1,711.45, a significant decrease. Increased vigilance and policing of violations helped decrease the scourge.