In 1918, more than 2,000 people in Orleans got the Spanish Flu

Historian urges people to document experiences during current coronavirus

“Overlooked Orleans” – Vol. 6, No. 11

Diaries and journals would provide the greatest detail from first-hand accounts. Although we have some limited oral histories from the 1970s provided by those who grew up during the pandemic, it is difficult to gain an accurate picture of the everyday lives of Orleans County’s residents. As a historian, I urge everyone to document the events we are living through so that future historians may have an opportunity to understand the impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on our lives.

In 1919, the New York State Department of Health provided documentation on the Spanish Influenza (H1N1) pandemic as it spread across the country. Early documentation suggests that Kansas was the first location where the disease was encountered. The Department of Health wrote that “the use of the term ‘Spanish’ is unfortunate and has served to create the impression that a new and especially dreadful disease has appeared.” Historians have noted that the term “Spanish Influenza” likely resulted from the lack of press censorship in neutral Spain during World War One, where the influenza outbreak was publicized far more than in France, the United Kingdom, and the United States.

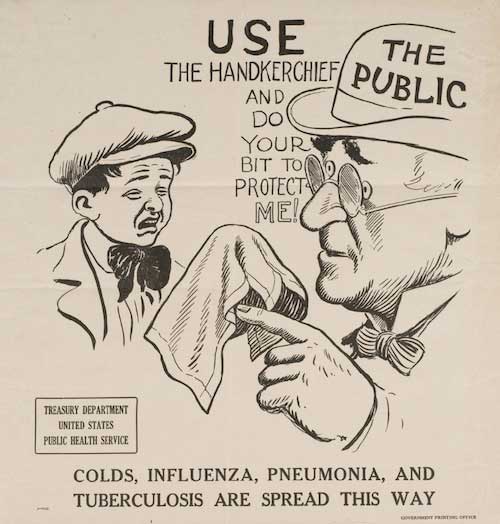

The Spanish Influenza caused a variety of symptoms, the most prevalent being a temperature between 102-105ºF, body aches, nasal discharge, and a dry cough. Some cases included red or watery eyes, a slightly red throat, nausea, and diarrhea. Of course, atypical cases presented with minimal symptoms but remained highly infectious. Lacking antivirals and vaccines, physicians relied upon isolation, quarantine, good personal hygiene, disinfectants, and limited public gatherings to mitigate the spread of the disease. The fact that approximately 30% of U.S. physicians were deployed into military service limited access to health services in rural locations throughout New York.

The New York State Department of Health relied upon preexisting policies and procedures to limit the spread of the virus. According to Sanitary Code, spitting in public places, on sidewalks, and on the floors of public buildings was forbidden and considered a misdemeanor. The Public Health Council also pushed for legislation that made it a misdemeanor to cough or sneeze without properly covering your mouth or nose. Physicians treating infected patients were encouraged to wash their hands frequently and wear gauze masks whenever possible.

When quarantining those with influenza, individuals were expected to remain secluded inside of a well-ventilated room when families were around. Dishes and utensils used for eating were to be boiled after use and handkerchiefs, napkins, and towels were burned after use. In locations where large portions of the community were infected, the Department of Health encouraged no public funerals, keeping windows open to ensure adequate ventilation, and closing amusement locations (specifically movies and theatres).

Although the Spanish Influenza was deadly to children under five and adults over 65 years of age, the virus also affected a relatively healthy segment of the population, those between the ages of 20 and 40. In Orleans County between October and December of 1918, the Department of Health estimated 2,279 cases of influenza across a population of 33,919 (approximately 6.7% of the total county population). Comparatively speaking, outbreaks of other communicable illnesses such as the measles (79 cases), Scarlet Fever (35 cases), and Tuberculosis (33 cases) dwarfed in comparison.

Newspapers provide a glimpse at the local response to the influenza pandemic. In early October of 1918, Brent Wood presented as the first confirmed case of influenza in Albion. The son of Rev. Edwin Wood of the Pullman Universalist Church, Brent was taken ill at Buffalo where he was to enter military service.

In the coming weeks, the Gillett and Benton Corners School Districts in Barre closed due to influenza outbreaks and other school districts followed suit. Teachers received their regular salary if the school closed on account of sickness, however, teachers who proactively closed their school would not receive pay for the duration of the voluntary closure.

In mid-October, the Medina Board of Trustees mandated the closure of all churches, theatres, schools, fraternal organizations, and public meetings, anticipating a need to shut down for one to two months. Although cases locally subsided into late October, the celebration of peace on November 11, 1918 caused a spike in cases throughout Western New York.