Illuminating Orleans – Local farmers, besides tending to crops, needed to build town roads

‘Corduroy’ and ‘Plank’ roads, and ‘Path Setters’ were thoroughfares through community, including the swamp

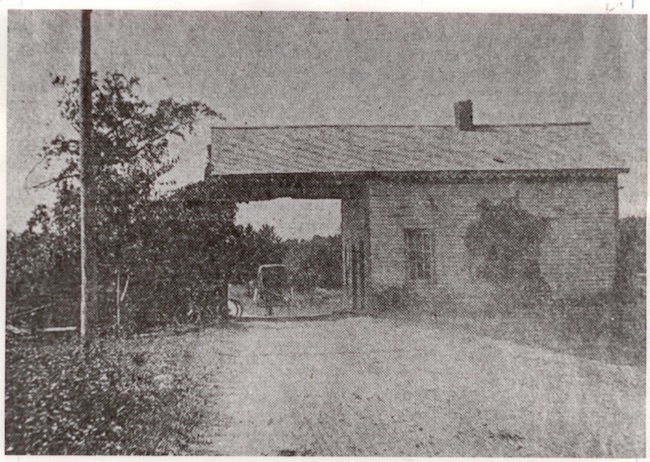

This photo taken in 1898 shows the toll house which stood near the Edwin McKnight farm between Medina and Shelby. H. Justin Roberts recalled riding through this toll gate as a young boy, in a lumber wagon, with his aunt and uncle.

By Catherine Cooper, Orleans County Historian

Illuminating Orleans – Vol. 2, No. 3

The diary of Hosea Ballou presented in the previous two columns have led to some questions.

A reader inquires if the diarist, Hosea Ballou, was related to Major Sullivan Ballou, of the 2nd Rhode Island Infantry whose poignant last letter to his wife featured prominently on The Civil War, a PBS series produced by Ken Burns. Major Ballou was killed at the Battle of Bull Run in 1861.

Sullivan and Hosea Ballou were both fifth generation descendants of James Ballou, son of Maturin Ballou (1627 – 1661), an Englishman of French descent, who was an early settler of Rhode Island. He had six children, three of whom lived to have families of their own. A family genealogy published in 1888 contains a remarkable listing of over 8,000 descendants.

In his 1851 diary, Hosea Ballou mentioned working on the roads in the Town of Carlton in the spring – this topic has also generated some discussion.

Prior to centralized government and mechanization, towns were responsible for roads. A road tax was assessed, eligible males were required provide labor or pay the tax. In addition to local labor, locally available materials: wood, stone, and later, quarried stone, were used.

H. Justin Roberts (1893-1991), a Shelby farmer, provided a very clear explanation of that system in an Oral History interview conducted by Anna Roberts Bundsuch in 1989:

“A farmer with a small farm in each town was appointed road commissioner. In addition to the road commissioner, there were path masters scattered throughout the town. Each farmer wanted to be path master because he could get the road improved past his farm. My father tried it for one year. The road past our house got a new topping.”

He explained that the road commissioner was salaried, but the path masters were not. The road commissioner would travel around the town in his horse and buggy to check the condition of the roads. Farmers would spend four or five days each year working on the roads, generally in the spring after the crops had been sown.

“There was no department – there was just the commissioner who worked with the path masters. When a road needed repair, the farmers along the road worked their highway taxes. They didn’t have anything to use but gravel. A farmer would be assessed so much money for road work. He’d take a dump wagon and haul for so many days to pay his taxes. A man who didn’t have horses would do the shoveling and use a pick. The gravel had to be shoveled onto the wagons.

Two or three big farms in a town, their assessment would be quite high, and they would put two teams and two wagons on.

The dump trucks were an ingenious affair. The bottom was made up of 4 x 4’s, there were side boards and end boards. The wagon would be filled up with gravel and then there would be a man on the road to assist in the unloading. He’d grab a crowbar and lift up the first 4 x 4; then as the wagon moved along, the gravel would fall out.

There were two gravel pits in the Town of Shelby. The town would pay the owner of the pit a little something for the gravel.”

He continued and explained the term “corduroy road”:

“I used to hear my father tell this story. In the early days, the road south of Medina was impassible through the swamp. So, they cut trees along the right of way: cut logs and laid them side by side all the way through. You bumped over each log and that is why they called it a corduroy road.”

Many of the early roads were called Plank Road, for example the Alabama Plank Road which led to the Sour Springs Hotel. Medina’s Main Street was originally referred to as Plank Road.

Mr. Roberts also described winter road work:

“In the winter, sleighs were used, but wherever snowbanks crossed the road, the snow was shoveled by hand. Mostly the farmers took care of their own roads. Farmers had 50 gallon kettles to heat water and maybe to boil beans to feed the hogs. They’d put a chain around one of those kettles and hitch it behind the bobsleigh and get a big heavy man to ride in the kettle. They’d drag that down one side of the road and the other side coming back to make a track.”

Since bone-chilling temperatures are forecast, another Oral History account from the Orleans County History Dept. Collection may be of interest. In an interview with Clifford Wise in 1969, Mrs. Minnie Allis described how one kept warm when traveling on a sleigh or cutter in winter:

“They had soap stones and these big buffalo robes to put on your lap; they had heavy underwear and top buttoned shoes and they put overshoes on and bundled your head up; fur mittens; they used to carry ear muffs to put your hands in.”

Burt Dunlap of Shelby, in a cutter, c1908. From the Scott Dunlap Collection, Medina Historical Society