Holley woman survived Titanic disaster, 106 years ago

“Overlooked Orleans” – Vol. 4, No. 15

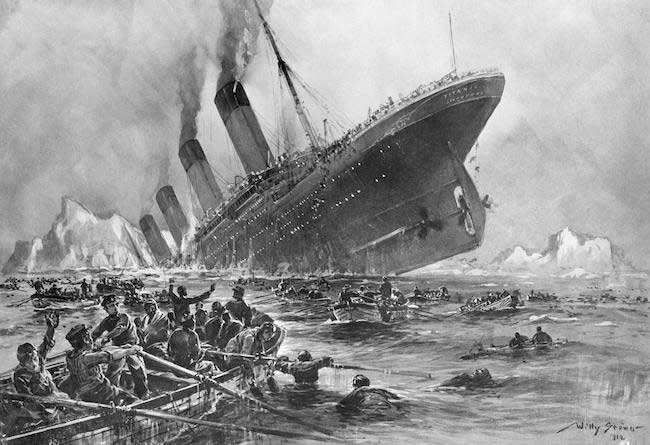

April 14th marks the 106th anniversary of the sinking of the R.M.S. Titanic and although I share a common surname, I can assure you that Dr. Robert Ballard is no direct relative of mine (that I am aware of). On that fateful day in 1912, the exquisitely decorated vessel struck an iceberg at 11:40 p.m. and was fully submerged within a matter of three hours. Of the 2,224 passengers, over 1,500 perished in the frigid waters of the Atlantic Ocean nearly 400 miles off the coast of Newfoundland, making it one of the most devastating maritime disasters in modern history.

Over the years, newspapers have recounted the stories of survivors while paying tribute to the victims as each landmark anniversary passes. Of the most notable local residents connected to the catastrophe, the story of Lillian Bentham of Holley is most frequently recalled. Of course, the story of May Howard (buried in Boxwood Cemetery) is also shared. So, I thought it best to thoroughly recount some of these recollections over the course of several articles starting with the story of Lillian Bentham.

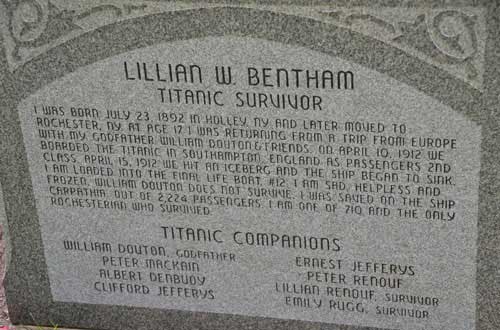

On July 23, 1892 a baby girl was born to Henry and Mary Jane Bentham of Holley, New York. The Benthams were natives of Guernsey in the Channel Islands where Henry learned the trade of stone cutting and stone dressing before immigrating to the United States. Given the number of other immigrants from the same region of the British Isles, it is likely that Mr. Bentham was aware of job opportunities in the booming sandstone quarries scattered throughout Orleans County. When Lillian was born, Henry asked fellow quarryman William Douton to be his daughter’s godfather. Both men were active in Holley’s I.O.O.F. Lodge No. 42 and presumably good friends.

Henry and Mary Jane Bentham suffered the loss of their daughter Daisy in early March of 1903 as the result of a year-long illness. Her obituary read, “As a young girl, Daisy was an exceptionally beautiful and charming child, with winning and attractive ways that made her a general favorite with all who knew her.” This eloquent eulogy is reflected through the broken daisy that appears on the young girl’s headstone in Hillside Cemetery. Eight years after the passing of Daisy, the family mourned the loss of Henry on October 24, 1911 following a two-year long battle with tuberculosis. He was remembered as a “…man of very social, genial nature, generous, kindly, and sympathetic.”

It is possible that this tragic event was a reason for 19-year-old Lillian to travel to Guernsey to visit family, likely her older sister Annie who was living overseas at the time. Bentham and two others, including William Douton and fellow quarryman Peter McKane, returned to Guernsey where many of the men had started their careers as stone dressers. During their time away, Mary Jane Bentham and her son Walter relocated to Rochester. On the return trip, Lillian and the party she was travelling with were set to return aboard the R.M.S. Titanic. She had purchased a second class ticket, number 28404, for 13 pounds while Douton and McKane shared a joint ticket, number 38403, which cost 26 pounds.

It was well known by passengers that the Titanic’s crew was pushing the ship’s limits in order to break record timing on her maiden voyage across the Atlantic. On the evening of April 14, 1912, Lillian retired to her quarters and prepared for bed when she was suddenly jarred by the ship’s collision with the iceberg. The elderly woman sharing her berth was sleeping peacefully when the accident occurred and the impact caused the woman to fall out of bed. A crew member passed the cabin and calmly told the two women that the ship had struck a fishing boat, encouraging both to return to sleep. Lillian fell asleep for a period of 20 or 30 minutes before the sounds of screaming men and women woke her.

She quickly threw on her clothes and made her way up on deck. Lillian reported the following scene to the Holley Standard which was printed on April 25, 1912, “The women and children were crowded together on both sides of the ship and were being put over the sides into the lifeboats. There were some men among them, mostly helping the women along, bidding them a good-bye and cheering them up. The rest of the men were crowded together, some kneeling down and praying, others standing like statues.” As more people crowded onto the deck a number of men, many being immigrants, attempted to jump into the lifeboats; they were shot and killed by crewmen.

Photo by Tom Rivers: This gravestone for Lillian Bentham was installed on Oct. 1, 2015 at Hillside Cemetery in Holley/Clarendon. Brigden Memorials of Albion donated the stone. Bentham lived to be 85, and remained in the Holley and Rochester region until her death on Dec. 15, 1977. Bentham was buried in Hillside Cemetery next to her sister, Daisy Bentham, who died at age 16 in 1904. Lillian never had a headstone until Brigden donated one about four decades after her death.

Lillian was placed in Lifeboat 12, the third boat lowered on the port side and was allegedly within an earshot of the Captain Edward Smith as he shouted, “Now, every man for himself, she’s going down.” The band played sacred music for the duration of the ensuing commotion, playing “Nearer My God to Thee” as their final piece. Bentham recalled everyone praying on their knees as the ship’s deck dipped below water. As the vessel submerged the boilers exploded, scalding and killing many on deck and those locked below deck. She watched as the ship broke in two before disappearing below the waterline.

As the lifeboats bobbed atop the water, men and women were occasionally plucked from the water while others were struck over the head with oars to prevent panicked survivors from capsizing the tiny boats. Lillian recalled a tragic scene that remained with her for the rest of her life; an infant with its hands either crushed or cut off was thrown overboard to “put it out of its misery. It was very weak and would have died soon anyway.” The dead were thrown overboard to make way for those survivors floating in the freezing waters. Many died from shock, the result of exposure to extreme cold. Those in the lifeboats huddled together, most in their nightgowns, unprepared for the frigid temperatures of the cold Atlantic night.

When the R.M.S. Carpathia arrived at New York City, Mrs. Emily Douton was present and ready to welcome Lillian and her husband. Word was sent early of the survivors of the disaster, but Emily’s first question to Lillian was “Where’s William?” In the months following the disaster, the Holley Lodge I.O.O.F. purchased a cemetery monument for fellow members Douton and McKane, whose bodies were never recovered. The stone was dedicated in June of 1912 and reads “Erected in Memory of Wm. Doughton & Peter MacKain lost at sea with S.S. Titanic April 14, 1912 by Holley Lodge 42 IOOF.” Emily Douton remarried twice before her death on June 30, 1923 from stomach cancer.