Historic Childs: The Erie Canal in the Town of Gaines, Part 2

Devastating canal breach in 1927 flooded community

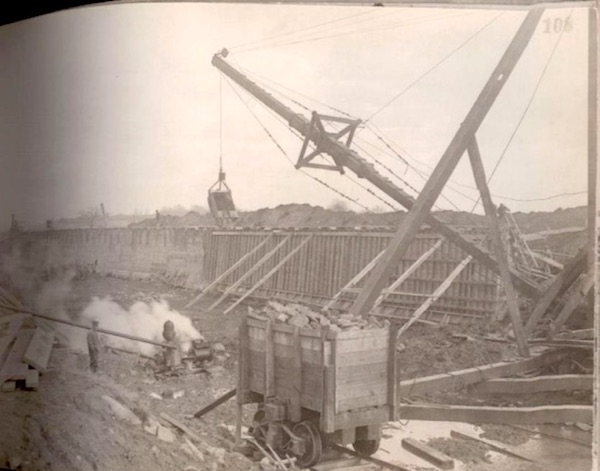

Photo courtesy NYS Barge Canal Western Division

By Doug Farley, Cobblestone Museum Director – Vol. 2 No. 43

Eagle Harbor, once a thriving Erie Canal community, was the scene of a devastating canal breach in August, 1927, that caused damages estimated at over $3 Million in today’s economy. The sleepy canal town instantly became the scene of an enormous work force numbering several hundred people that worked 24 hours a day to restore canal commerce.

The underpinning of the disaster can be attributed to the design of the canal in what became known as the south wall of the “Trough at Eagle Harbor.” During the Barge Canal expansion in 1912, a massive embankment or trough with a height of about 50’ feet raising above the level of Otter Creek was created to contain the canal and pass over the creek. The embankment was constructed from earth, concrete and stone.

A portion of the embankment passing over Otter Creek today, known as state canal culvert #86

A short excursion along the towpath at Eagle Harbor quickly identifies the immense scale of the construction project, also seen in the picture above. The creek itself was channeled through a culvert that was buried 6’ beneath the canal, creating a trough of water 12’ deep above.

On August 3, 1927, bridge tender, Leon Walters, received word from two boys that they had seen a small leak open up in the canal near the embankment. The small leak foretold of the disaster that was about to follow. A local man, L.E. Bennett, reported seeing a 3’ square hole open up later that day.

This opening began spilling thousands of gallons of water from the canal into the surrounding countryside in short period of time. The breach occurred about 100’ west of the Otter Creek culvert. Quickly, a massive hole opened up and the south wall of the canal broke apart creating a hole 50’ across and 7’ deep.

Photo courtesy Orleans County Historian

Newspapers stated that canal officials estimated 1 billion gallons of water spilled out of the canal into the surrounding fields, creating an artificial lake about 2 miles long by one-half mile wide with a depth of 20’-60’ throughout. Numerous houses were flooded with some victims stranded in their second stories until the next day.

The reconstruction efforts began immediately and were supervised by Canal Commissioner Thomas Farrell. Early estimates stated that the canal west of Rochester would need to be closed for ten days, but when the full scope of the disaster was realized, the project dragged on for six weeks. Some sources reported that during that time, upward to two million bushels of grain were stopped at Buffalo due to the canal break, along with untold amount of other agricultural products from other locales around the Great Lakes. Local farmers pleaded with Farrell to keep the canal open to the Lattin Bridge Guard Gate so that commerce into and out of Albion (eastbound) could be maintained to help minimize the impact in Orleans County.

Over 200 men were put to work, round the clock to make the repairs. Heavy equipment operators were employed to operate about 20 trucks, 6 steam shovels, concrete mixers, pile drivers and other pieces of earth moving equipment were utilized to complete the project.

Photo courtesy Orleans County Historian

The break became an overnight sensation, drawing motorists thought to number in the thousands to the region. In addition to the cost to repair the canal, many local farmers suffered devastating losses, the ill effects of which lasted a few years in some cases. Local farmer John Potter reported his field of potatoes was submerged under 10’ of water for weeks. Other farmers reported losses of cabbage, tomatoes, cucumbers and grain products.

Repaired canal structures passing over Otter Creek at Eagle Harbor today. Note use of concrete retaining walls on both sides of the canal.

When final reports were published, state officials postulated that the underlying culprit in the disaster was a colony of errant muskrats, close cousins to the otters of Otter Creek fame, that had burrowed into the wall of the embankment, thus setting up the cataclysmic series of events that led to this historic disaster.

The 1927 Eagle Harbor canal breach is probably the most well known, but not the only historic canal breach in Orleans County. A 19th century breach occurred in the 1850s, a few miles east of Eagle Harbor, near the Joseph Lattin farm in the Town of Albion. At that time, it was reported that a canal boat was actually washed out of the canal and deposited into the adjoining farm land.

Following the canal repairs, Bartlett Lattin helped return the boat to its rightful location back in the canal. More specifically, Lattin’s mother and sister came to the rescue, too, by supplying homemade soap that Bartlett used to grease the skids used to move the boat off dry land. The equipment utilized was actually provided by George Pullman who used an ox-powered machine that his father developed to lift and move houses that were in the way during the canal expansion which was ongoing at that time.

Pullman, a furniture manufacturer in Albion, was working a contract that the state had given to Charles Danolds to facilitate the canal enlargement in this region. Pullman, of course, went on in subsequent years to become a railroad tycoon with the improvements he made to railroad sleeping cars that became known as Pullman cars.

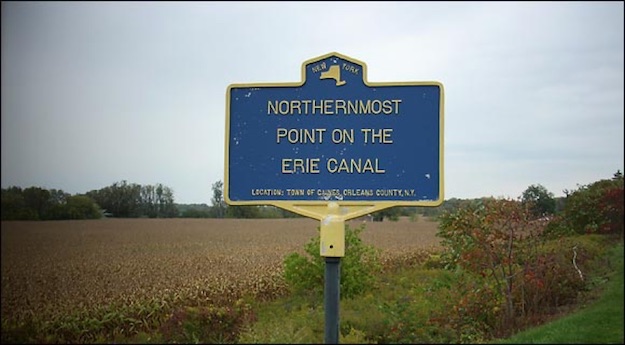

Another 19th century canal break in the region occurred around 1870 in the Town of Gaines, very near the northernmost point on the canal. Water from that breach flowed out in great force, making its way to Beardsley Creek on the north side of the canal. It is said that a local farmer, David Bullard and his daughter, were working in a chicken coop at the time of the deluge of water in the creek, which expanded to include the chicken coop in its wake.

The chicken coop, and all of its occupants at the time, were raised form its moorings and carried downstream at a heart-stopping pace. Eyewitnesses reported that Bullard’s daughter jumped out of the chicken coop as it was passing over Gaines Basin Road but Mr. Bullard rode it out until the coop eventually crash landed at a tree where Beardsley Creek crosses Gaines Basin Rd again at the Sanford Farm.

Workers at the site of 2012 canal breach, photo courtesy Times-Union, David Duprey/AP

A much more recent canal breach took place in 2012, once again in the proximity of Gaines Basin. On the evening of July 30, passersby on Albion-Eagle Harbor Road near the Lattin Bridge, noticed that a slight depression in the highway had formed in a very short amount of time. Retired County Historian Bill Lattin reported, “I was the last car that made it through. I felt a huge ‘kerplunk’ as my car kind of bottomed out.”

The next car to approach the scene came upon a gaping 60’ wide by 16’ deep sinkhole that had opened up in that same spot. Luckily, a state worker had arrived on the scene to flag that motorist down.

It was discovered that extensive damage had occurred to a large culvert pipe under the Albion Eagle Harbor Road at that spot. The discovery was followed by the closing of a 25-mile stretch of the canal from Middleport in Niagara County to Holley in Orleans County. Contractors, meanwhile, hauled in 200 tons of crushed stone to fill the sinkhole in the weakened rock-and-clay embankment.

Photo by Tom Rivers: Construction crews led by C.P. Ward were mobilized late into the night of July 30, 2012 to fill a sinkhole on Albion Eagle Harbor Road and a path along the Erie Canal. Crews worked late into the night to fill the hole and stabilize the site so the canal wouldn’t flood two neighboring state prisons.

The sinkhole nearly collapsed the embankment that held back the Erie Canal. Had the wall been washed out, officials feared the two state prisons next to the road would have been flooded.

Dump trucks hauled stone from Keeler Construction in Barre to fill in the road and canal path.

Repairing the road and path cost the state $1.3 million to fix. The sinkhole forced the state Canal Corp. to close a section of the canal in Albion for about 2 ½ weeks.