Historic Childs: Popular Images of Yesteryear, Part 6 – The Angelus

By Doug Farley and Bill Lattin – Vol. 3 No. 7

GAINES – Surely one of the most recognizable and renowned fine paintings of the 19th century is “The Angelus” by Millet, an image that was widely reproduced. The Cobblestone Museum has two such images on view.

The one above, circa 1885, is a lithograph which was affixed to canvas on stretchers and put into a style of frame normally used for paintings. This gives it a more realistic appearance as a painting. Our rather dark colored version here hangs in the Cobblestone Ward House dining room.

The other example at the Cobblestone Museum which is represented below, appropriately hangs in the Vagg House. This particular print dates to circa 1925 and is also in its original frame. A companion print, “The Gleaners,” by Millet hangs nearby.

The reproduction of this famous painting remained very popular with the general public over many decades. The original painting was completed in 1859 by Jean-Francois Millet, and is an oil on canvas, measuring only 25½ by 21¼ inches. Certainly, through improved printing techniques of the Industrial Revolution, great art such as this became accessible to middle-class people.

In these two small porcelain vases, circa 1900, we see transfer images of The Angelus on one, and The Gleaners on the other.

The imagery of these two peasants praying in a potato field was a popular sentimental 19th century religious subject. Although Catholic in origin, the subject matter seemed to cross all denominational boundaries.

The print below dating to 1890 was originally mounted in this frame with an oval format.

The potato diggers have stopped their evening work to pray because of the tolling of the Angelus Bell that they hear from the church spire in the distant village.

In the Catholic tradition, the Angelus Bell sometimes referred to as the Ave Bell, was typically rung three times a day at 6 a.m., noon and 6 p.m. This tolling consisted of nine rings each time, with three rings followed by a pause, three more rings followed again by a pause, and ending with a final three rings.

An older interpretation commemorated the Resurrection of Christ in the morning, his suffering at noon, and the Annunciation in the evening. In 1907, the Orleans Republican reported an interview with a local Polish resident, then a member of St. Mary’s Assumption Church, who described the frequent ringing as follows:

“At the hour of work it rings to remind them that God has given them the strength of labor. When it rings at noon, Poles are again reminded of the Giver of Temporal Blessings, and at night it calls for Expression of Thankfulness for what God has done for the people throughout the day.”

Here we see a decorative plate in the Museum collection, circa 1900, about 10 inches in diameter.

As a side note, when a church bell is tolled, it does not swing or move but rather is rung by pulling a second rope which hits the bell with a large hammer.

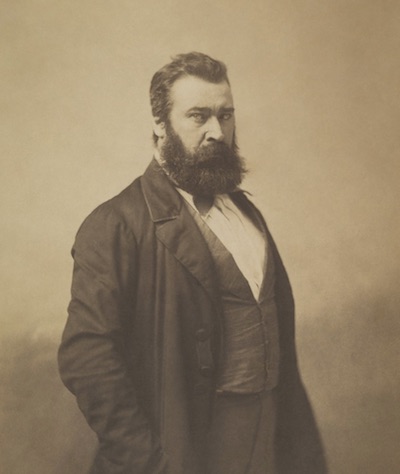

Jean-Francois Millet (1814-1875) was the first child of Jean-Louis-Nicolas and Aimee-Henriette-Adelaide Henry Millet. They were members of a farming community in the Village of Gruchy, in Greville-Hague (Normandy). He first studied painting in 1833 with Paul Dumouchel, a portrait painter in Cherbourg.

By 1835, he was able to move to Paris, where he studied at the famous Ecole des Beaux-Arts. In 1840, his first painting, a portrait, was accepted at the Paris Salon. In 1841, he married Pauline-Virginie Ono, but she died of consumption two years later. In 1853, he married Catherine Lemaire and they would have nine children.

Millet became one of the founders of the Barbizon School of Landscape Painting in rural France during the mid-19th century. Other noted artists of the group included Corot, Daubigny and Rousseau. Barbizon is a small village near Paris.

The Barbizon style is realistic, but done with great respect for technique of brush work and use of paint for speaking on its own behalf. It is a style which bespeaks the oncoming Impressionists in the later 19th century. Millet spoke of The Angelus as follows:

“The idea for The Angelus came to me because I remember that my grandmother, hearing the church bell ringing while we were working in the fields, always made us stop work to say the Angelus Prayer for the poor departed.”

This miniature plate, only 1½ inches in diameter, was probably a souvenir that an American tourist acquired on a trip to France in the 1940s.

This great painting is a reflection of the simplicity of peasant life, so dependent upon the rhythms of life and the Catholic faith. It was actually commissioned by an art collector from Boston, MA, and was somewhat finished in 1857. However, Millet later added the church spire in the distance and changed the title which originally was “Prayer for the Potato Crop.”

When the purchaser failed to take possession of it in 1859, Millet later sold it receiving only $400. Other well-known and famous paintings by Millet include The Sower, 1850, and of course, The Gleaners, 1857.

(Left) The Sower, Millet, 1850 (Right) The Gleaners, Millet, 1857

The popularity of The Angelus remained steadfast even into the 1950s, with the paint-by-numbers version below. We can only add that real artists, those with training, scoff at renditions such as this. It does however show the undying appreciation of The Angelus theme.

“The Bells of Angelus call us to pray with sweet tones announcing the Sacred Ave.” 1st Verse of Lourdes Hymn.”