Historic Childs: Pioneer women were critical in settling hamlet

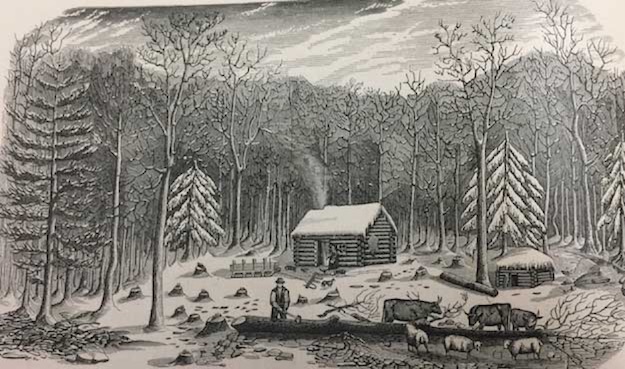

“The Pioneer Clearing,” – Emery A. Philleo, 1888, courtesy Niagara County History Center

By Doug Farley, Cobblestone Museum Director

Volume 2, No. 21

Authors note: In preparation for a prior article written to highlight the story of Delia Robinson in the Hamlet of Childs, I was fortunate to have been drawn to her book, “Historical Amnesia,” wherein she describes a few of the amazing stories of women in the pioneer settlement of the community. With Dee’s help, as well as a few others, I present this article on Pioneer Women in the Hamlet of Childs.

It’s seldom been mentioned, but common sense tells us that roughly 50% of our pioneer settlers were women. The majority of settlers in this county were immigrating from New England or from eastern New York settlements. These men and women brought with them strong moral and religious convictions, along with an amazing appreciation for the value of hard work.

The everyday activities for both men and women centered on securing food, clothing and shelter. To quote a phrase that has grown out of fashion, “women’s work” meant preparing the food, sewing clothes, assisting with the crops, and helping build and then maintain the early log, brick or cobblestone home. It has been said, “A man works from sun to sun, but a woman’s work is never done.” But, perhaps Dee Robinson said it best, “Women’s skills were a necessity, not a nicety.”

Mary Jane P. Danolds, unsigned, c1855, The Cobblestone Society & Museum

After setting up the initial settlement, two other emerging priorities were always schools and churches. In the Hamlet of Childs, women were front and center in the development of the religious society through their efforts in the formation of the Universalist Church, and also through serving as teachers for the District #5 Schoolhouse. In these endeavors, pioneer settler Mary Jane Danolds, shown above, is credited by historians with proposing the first name for the church, “The Church of the Good Shepherd.” In like manner, for the hamlet’s school, in its 103 years of service to the district, over 30 different women served as teachers, outnumbering men two to one.

Women’s work in the hamlet was arduous and time consuming. Starting with taking care of the log house, it included the everyday chore of sweeping the ever-present dirt floor and tending to the wood burning fireplace with its constant infusion of soot and dust into the home. Cooking three square meals daily over an open fire seems tough enough, but add to that the preservation of meat and vegetables for winter use through smoking and canning, all without running water, and one begins to appreciate the monumental task presented in just feeding one’s family.

Now add making soap, candles, thread, spinning, weaving, bearing and raising children, planting and harvesting crops, chopping wood, washing, mending, and the list goes on. Years ago, people used to say of a local couple where the husband was rather sedentary, “Hubby holds the lantern while Grace chops the wood.”

Courtesy Holland Land Office Museum

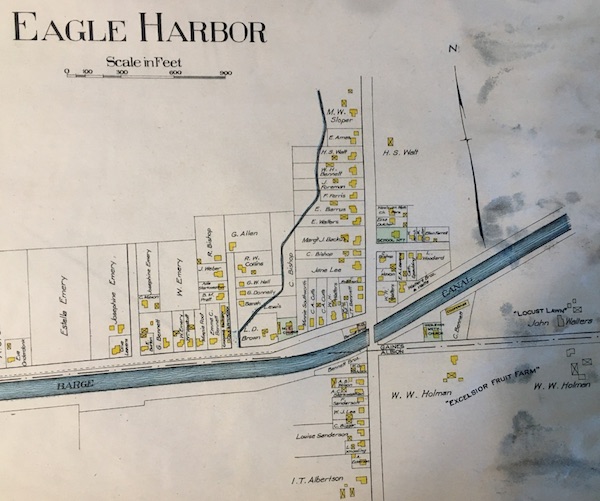

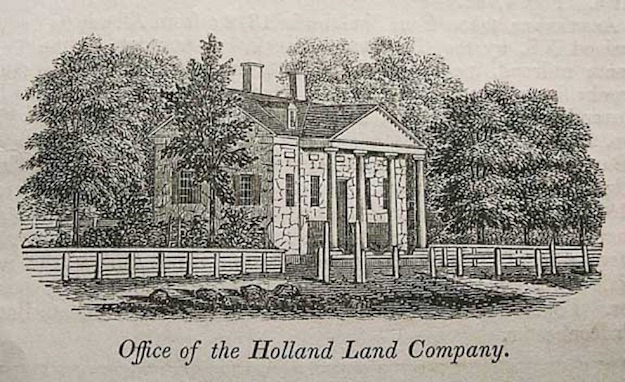

Every community is proud of its list of “firsts,” be it first church, first doctor, first store, first stone mason and more. But few, like Childs, can document that their first pioneer settler was a woman. In the records of the Holland Land Office in Batavia, one can see the first recorded “article” of land in what we now know as the Hamlet of Childs, was taken by Elizabeth Gilbert. Her land, a little over 123 acres, located on the Ridge near today’s Brown Street Road, was assigned to Mrs. Elizabeth Gilbert for the payment of $1.

Those requesting an article of land, then had ten years to pay the remainder of the purchase price, usually about $2.50 per acre, at which time the deed would be given to the settler. Elizabeth arrived in the region in the early 1800s with her husband, but no known record exists that lists her husband’s name. Two years later, in 1809, Mr. Gilbert died. Elizabeth and her niece and two children remained on the article of land and continued to make the payments. During that time, Mrs. Gilbert tended to all of the normal “women’s work,” and assumed with panache all of the hunting, fishing, plowing, sewing seed, tending animals, building barns, harvesting crops, felling trees, handling the ox team, and many more duties that would normally have fallen upon her husband.

Historians record that Elizabeth Gilbert not only attended to her own farm and household, she was present when her neighbors, Noah and Polly Burgess, arrived to their wilderness “article.” Not unlike Elizabeth’s own husband, Noah Burgess fell sick shortly after his arrival, and the difficult work of cutting trees, dragging them to the building site with a team of oxen, and building a log cabin was attended to by Polly Burgess and her neighbor, Elizabeth Gilbert.

The work of the farm wife, while often times unnoticed by historians, in some instances, when the household chores fell upon the male in the family, a record of the disturbance was made. One such record can be found in 1825 when an early settler wrote, “I can get no girl to work and I was obliged to take care of my sick wife and do all my work indoors and outdoors. I (also) had to milk, churn, work butter, wash and iron clothes, mix and bake bread, and in fact do all that had to be done. I finally found a woman to work until my wife got able to be about.”

The death of a pioneer husband many times forced young families to pick up stakes and head back east to the security offered by other family members. But, alternatively, many fatherless families decided to stick it out and stay with their articles of land, doing the chores and doing what was necessary to pay the Holland Land Office for their properties.

If a husband died intestate (without will), Surrogate Law said a widow had use of 1/3 of her husband’s estate during her lifetime, a provision that was called a dower. This included 1/3 of the acreage as well as the dwelling. In several instances, this provision was applied with exacting detail. One case reads, “The widow has use of the south part of the lower room of the dwelling house, divided by a line running from the south side of the bedroom door to the center of the fireplace, including the room south of the chimney. Also, the south part of the chamber as it is portioned off with the privilege of a passage in the north door and entryway and stairs into the chamber. Also, all the scaffold over the stable and barn floor, the south bin of the granary and the west stall in the stable, with the right to go in and out at the door, together with the land on which the above described parts of said buildings stand.” Fifteen women from 1828-1855 claimed their right of dower in Orleans County.

Cynthia Lee Proctor

It is rare to find an early history of the hamlet written by a woman. A few exceptions exist and their written point of view brings clarity to the lives of the “silent half” of the local citizenry. The following commentary was penned by Cynthia Lee Proctor, fourth wife of John Proctor of Childs. It was written in 1870 at the request of the Pioneer Association of Orleans County which formed in 1859.

“Having often been solicited to give a history of my pioneer life, I have excused myself by thinking that no event of my life has had been of sufficient import to record it. But as the interest of our society depends upon individual experience, such as it is, I give it to you. I was born in the town of Wardsboro, state of Vermont, in the year 1803. My father and mother, John and Sara Lee, were natives of Massachusetts and moved to Vermont shortly after they were married, where they remained until 1804 when they moved to New York. My mother had 12 children, ten of whom survived her. In the spring of 1816, my father and eldest brother Charles Lee, came to this far west county to look for land. They made a purchase on what was then the Town of Gaines, County of Genesee. (Note: Orleans County not formed until 1824.)

In a short time, two of my brothers and a hired man started on foot, one hundred and fifty miles, to commence the new and strange enterprise. They cleared the land, got in five acres of wheat, built a log cabin and chopped down 7 acres of timber, preparatory for clearing off and putting in spring crops. On the last day of February 1817, our family, 12 in number, arrived at our new home, in which was a young man and his wife who had taken shelter until they could build a log cabin. I was the youngest of four unmarried sisters. The oldest went east that summer to teach school, as there was not a schoolhouse, I think, south of the Ridge Rd.

The Pioneer Homestead – courtesy Orleans County Historian

Our floor was split logs and the doors were blankets, as yet no doors could be obtained. It was not long before we had board for chamber (bedroom) floors, doors, windows, also a chimney and oven. They made bedsteads of round poles called Genesee bedsteads, but they answered every purpose and most happy were we when we had a chamber to put them in, although the way to reach it was by a ladder.

“The Opening of the Erie Canal-October 26, 1825,” Raphael Beck, 1928, Courtesy Niagara County History Center

It was not long before our spinning wheels were got in order and the hum of four wheels indoors and as many axes outdoors was the only instruments of music. But not infrequently did our voices rise above the continual din and echo on the surrounding woods.

We walked twice during the first summer to Maple Ridge to attend meeting, which was held in Mr. Wyman’s barn. I think Elder Gregory preached. (The author notes these were more than likely Methodists.)

Late in the fall of that year, my father got his horses home, which had been pastured in Ontario County. Cattle could get their living in the woods, the only trouble was the flavor of the milk and butter, and hunting for the cows. The boys would start after them, taking a tin horn so it they lost their way or got belated, they would blow the horn, and then we would do the same from the house, and they could then follow the sound. That was a dismal sound when we heard the horn in the evening and frequently the howl of wolves at the same time. On one occasion every one of the family was awakened from sleep by the noise of the wolves not more than fifteen rods from the house. They had attached a flock of sheep and killed five and most likely would have killed them all if they had not got fighting among themselves and aroused the family.

After we got horses, my sister and I took a ride of 13 or 14 miles to visit a friend in the Town of Yates or North Woods as we used to call that section of country north of Ridge Road. After we got to the Ridge, the ride was delightful. We went about three miles north of the Ridge, but what a road, if road it could be called. The mud and water would frequently come up to our feet in the stirrups. I had no desire to visit the place again, and did not in some 20 years, when I could hardly realize it was the same place.

I think as the youth listen to stories of pioneers, they are apt to get the impression was one of hardship, privation and toil, but such was not my experience. We had our social pleasures just as much, then as now, but less time to argue about styles, conventionalities or grades of society. Ture, we labored hard, but that was the fashion, and we all adopted it. An indolent man or woman was not in fashion.

Another source of joy, which none but a pioneer could appreciate, was to witness the improvement constantly going on, and our hope of better days more than realized after the first year. With what joy the (Erie) canal was received and surely it was the making of western New York at that time. By this way it was my privilege to come to Medina on the first boat that passed through to this place.

My sister, Esther, who married William C. Tanner, taught school in Eagle Harbor in 1821. A little incident took place in the school worth mentioning. All at once a little boy called out ‘a snake, a snake,’ and there in the corner of the room was a black snake crawling up the log with evident intention of getting upstairs. She had nothing to encounter so formidable a foe and sent the children for help, but he was gaining his point so fast she took the log of a bench, pulled him down and killed him. It measured 5 feet 9 inches. I taught in the same house the next season and I kept a good watch for snakes. I taught six months at $1 per week, the then common price.

In 1823 we buried our dear father and mother. They were surrounded by their children, not one having settled more than four miles from home.

I am thankful to my Heavenly Father that I have been permitted to live in this period, from the wilderness to behold this beautiful country; from ignorance and superstition to see the love, science and a consistent view of the character of God enlightening the minds of the rising generation and bring all souls more in harmony with His Divine Law. Love to God and Love to man. Cynthia Lee Proctor”

Lithograph from the Cobblestone Museum Collection