Historic Childs: Outhouses in the Hamlet

By Doug Farley, Cobblestone Museum, Director

Author’s note: Sometimes it helps to take a look at the lighter side of things, and writing a story on the history of outhouses, is one of those things. I hope you enjoy the underlying humor in the whole subject.

Here you see Museum Director Doug Farley (left) and former Director Bill Lattin, “doing their duty,” while “sitting down on the job” in one of the Museum’s historic outhouses.

The history of the “necessary building” out back provides some interesting stories of bygone times and increased sensibilities. If you are old enough to remember a visit to a grandparent’s house and seeing an outhouse, you’re probably “getting” old. If you once had an outhouse yourself, let’s face it, you’re “really” old.

Prior to the installation of indoor plumbing, I would dare say most homes in the Hamlet of Childs had outhouses to handle what some call “number one” and “number two.” There are at least seven outhouses that remain today, and probably a few more that aren’t on the map.

In addition to its National Historic Landmark cobblestone buildings, the Cobblestone Museum has a fantastic collection of outhouses. In case you weren’t aware of that, we’re providing a little glimpse inside, outside and underneath this little discussed architectural collection.

The 1880’s Eastlake style outhouse located by the Print Shop was the first building moved onto the Museum grounds, taking place in March 1977.

The Eastlake outhouse was moved from its location at Five Corners at the former site of a foundry and furniture factory, seen here. The image shows the outhouse on the north side (left) of the brick house that sat at the intersection of Routes 98 and 279. The house was razed shortly after this picture in 1977.

The property owner at that time established a price of $250 for the historic outhouse and Museum Director Bill Lattin made an inquiry with longstanding Museum member Nettie Ferris who provided a donation that the Museum Board used to make the purchase. Nettie, an official with the Daughters of the American Revolution in Albion, recognized the significant architectural importance of the Eastlake period.

Museum volunteer Pete Roth arrived with forklift to move the Eastlake outhouse to the Museum grounds..

The outhouse made the trip up Route 98 past the Joseph Vagg Blacksmith Shop, seen here in 1977 before Museum restoration, and before the creation of the Route 98 artisan campus.

The Museum originally placed the outhouse in back of the Ward House. Former Museum Director Bill Lattin is seen here standing in the outhouse doorway with his 3-year-old daughter, Adrienne. She is holding a sign, seen at right that describes the Eastlake style of architecture. Also helping out with the move are Bob Leslie (left), Charlie Haight (right) and Bob Krause (center), newspaper reporter.

Several years later, the Eastlake outhouse was moved to Route 98 following the acquisition of the Print Shop that matched its architectural style.

The Print Shop Eastlake outhouse is actually fairly pretentious in design, as far as outhouses of its day were concerned, sporting paneled walls, ventilator and two sliding windows

In 1979, the Museum received a donation of its next outhouse, a very early 1830 privy donated by Dee & Tom Hockenberry. The 1830 outhouse was located at their house on the corner of Routes 104 & 279. This restored “beauty” is actually the oldest structure on the Museum campus. It was originally located at the first bank in Orleans County.

It is interesting that this outhouse is probably twice as large as typical outhouses of the time. Perhaps, it was deliberately ostentatious to embellish the success of the bank’s financial prowess. The Museum undertook a full exterior restoration of the 1830 outhouse in 2018, as seen here. This photo shows museum volunteers Bob Albanese, at left, and Ken Capurso.

Retired Director C.W. “Bill” Lattin is leading the Outhouse Tour outside the 1830 outhouse following the restoration in 2018.

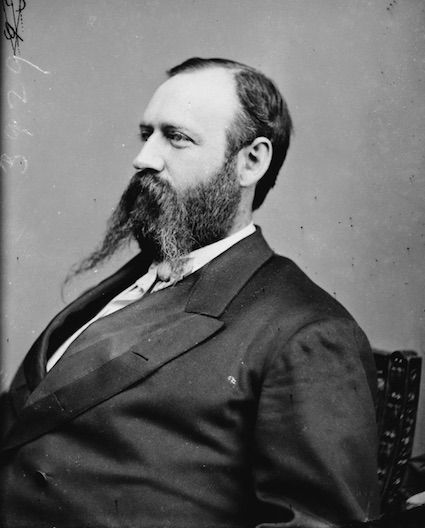

The third outhouse to make the trek to the Museum campus was donated by Mr. and Mrs. Edmund (Vernieta) Cooper. This privy was originally located at the home of Gov. Rufus Bullock in Albion. Rufus Bullock, born in 1834, moved to Albion at age six, and attended the Albion Academy. His home was diagonally across from the Baptist Church at Liberty and West Park Streets.

In 1860 Bullock moved to Augusta, Georgia, where he served as Lieutenant Colonel in the Confederate Army, and was with Robert E. Lee as he surrendered at Appomattox. Following the war in 1868, Bullock was elected governor of Georgia during the Reconstruction Era, the first elected Republican governor in the state. He retired to Albion in 1870 and is buried in Mt. Albion Cemetery.

In 1920, E. F. Fancher bought the Bullock House and installed indoor plumbing, and the old outhouse was moved to a tenant farm on Lime Kiln Road. In 1923, the privy was moved once again to Fancher’s father in-law’s home, Nelson Welch, on the Ashwood Road in Carlton. The outhouse was later given to the museum by the Coopers. Mrs. Cooper was the daughter of Nelson Welch. Here we see Bruce Sartwell operating his forklift to raise the Bullock outhouse onto a trailer for transportation to the museum.

Once on site, neighbor, Zambito Produce, offered forklift assistance for the short hop to its current location behind the Ward House, which once served as a parsonage for the Cobblestone Universalist Church.

Gerard Morrisey and Pat Farnham are shown near the Bullock outhouse during the Ghost Walk in 2019. This outhouse has a double hung window and a box inside that holds corncobs for cleaning up after using the facility.

This beautiful Greek revival outhouse, engineered by Joe Martillotta, arrived next. One of its unique features is that it’s a five holer! There are three seats for adults and two smaller ones for children. This privy has a plastered interior and colonial restoration wallpaper. It came from a c.1838 cobblestone house once owned by the Goheen family on Culvert Road. Mary Zangerle (floral blouse), a Goheen family member, inspects the restored Greek revival outhouse on the Museum’s Route 98 campus, alongside Farmers Hall.

One may ask, “What was the reason for so many holes?” I don’t think we know for certain, but some have conjectured that the additional holes allowed for some longevity between cleanings. Continued use of only one hole would soon create a situation where what you were depositing would came back up to visit you.

In addition to its collection of privies, the Museum also has an authentic water closet, which is really a misnomer, in that while it was a closet, it didn’t have any water. The small closet under the west staircase off the church lobby was used as such. The photo shows one of the only places in the church that clearly depicts the interior rubble wall associated with cobblestone masonry construction. The Museum has placed a commode in the closet which visitors find most fascinating.

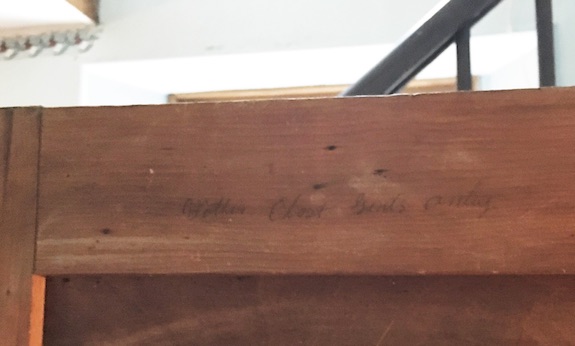

Written in old style handwriting with pencil on the inside of the west closet door it states, “Water Closet Gents Only.” However, no such labeling exists on the similar closet on the east side of the entryway. It is assumed that the ladies had their own parlor and water closet downstairs which was off limits to men and boys.

Folks are usually surprised to learn that there was never any running water at the District #5 Schoolhouse in Childs, even as late as 1952. There are, however, boys’ and girls’ outhouses at the school house with construction dating from the 1930’s.

The boys’ outhouse even has a urinal.

In the late 1920s, few decades before the school closed, the school’s trustees agreed to install chemical toilets inside the boys’ and girls’ entranceways. A toilet “salesman” had promised, “No smells will ever be detected.” That turned out to be an empty promise. Following the installation of the chemical toilets, they removed the old outhouses, which they felt were outdated “technology.”

It wasn’t too long until the “odor-free” chemical toilets displayed their true shortcomings by creating a malodorous nightmare. While eating crow, the trustees decided to remove the offensive toilets and rebuild new outhouses in the 1930s, which still remain today. With careful observation of the floors in the schoolhouse one can still see the holes cut in the entryway floors to accommodate the toilet incursion. The holding tanks in the basement under the toilets were removed in the 1930s.

Here is a story Janice Barnum Thaine told about herself when she was in first grade at the District #5 School in Gaines. The school is now part of the Cobblestone Society Museum and is a National Historic Landmark. One of the unique features in the schoolhouse is a sloping floor which gives eight inches of elevation in the rear of the classroom where Janice sat.

Janice remembers that the teacher had a flip-flop sign that hung on the wall behind the teacher’s desk that controlled access to the outdoor facilities. One side of the sign stated in large letters, “Out,” and the other side had a pretty picture. When the sign displayed the “picture,” a student could raise his or her hand to ask the teacher for permission to go outdoors to the restroom.

But the teacher, the arbiter of discipline, would only allow one pupil to go “Out” at one time! If granted permission, the student would flip the flip-flop sign to read “Out,” on the way out the door. That meant that all other students should not even consider raising their hand and asking for permission to use the outhouse until the sign is flipped back to the pretty picture by the returning student.

One day, in the late fall of 1932, Janice raised her hand seeking permission to use the outhouse. The teacher looked at the sign which read “Out,” and said, “I’m sorry, someone else is out so you’ll have to wait your turn.” After a few minutes, Janice tried again, and the teacher said, “I’ve already told you, you’ll have to wait your turn.” More time passed and Janice tried a third time, in an angry tone the teacher replied, “How many times do I have to tell you!? You’ll have to wait your turn!!”

Well more time passed and Janice, of course, couldn’t wait any longer, and had an accident. Later in life, Janice offered, “That’s the exact moment I realized that the school had a sloping floor.”

It seems a little trickle of “number one” ran right down the floor, under the students’ desks, to a hot floor register placed directly over the furnace. It sputtered, “Pssst, Pssst, Pssst,” as each drop hit the hot furnace. And, then came the unmistakable aroma which permeated the room. Everyone knew, of course, that Janice had an accident. How embarrassed she was, but not as embarrassed as her older sister, Elda, who wouldn’t even walk home with her that day after school.

When such troubles as this occurred, the teacher would send the child next door to visit the good-hearted neighbor, Lucy Janus, who was always prepared with a clean dress, undies, and trousers for someone who might need cleaning up. Sometimes a similar situation with soiled or ripped clothing would occur when the children played games outdoors, and Mrs. Janus would always come to the rescue. You see, unlike today, there were no teachers’ aides or school nurse in the old fashioned, rural, one-room schoolhouse that would take care of such problems.

The newest addition to the Museum’s collection of outhouses is located at the Vagg House. During the planning stages for the advent to this new property for the Museum, Bill Lattin undertook the modern construction, of a replica outhouse, using all salvaged lumber, patterned after an outhouse located at the Gaines Basin Schoolhouse.

In the early 2000s, to highlight the Museum’s unique “collection” of outhouses, Georgia Thomas provided a special tour of just the privies. Bill Lattin also provided Outhouse Tours in 2018 and 2019. Perhaps it’s time to “drop-in” again. (Sorry, I had to offer at least one more pun!)