Historic Childs: Musical Instruments – Part 3 – The Melodeons

By Doug Farley, Cobblestone Museum Director – Vol. 3 No. 12

GAINES – As we mentioned in an earlier article, the Cobblestone Museum musical instrument collection has been enriched with a variety of artifacts that represent by-gone eras of musical entertainment.

The Museum is actually quite fortunate to have in its possession two historic Melodeons. The first melodeon came to the collection in 2010 from Kent, NY and the second one came a decade later from the Fancher family in 2020.

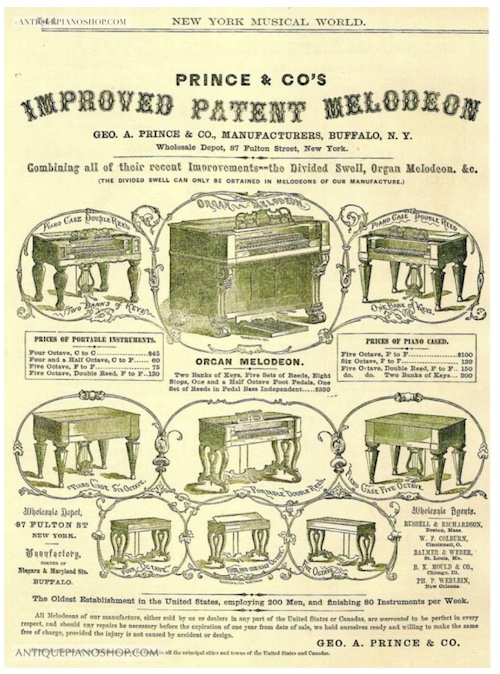

During the latter half of the 19th century, Buffalo, NY was described as the “Melodeon Capital of the World,” which is odd considering many folks from this area today probably don’t even know what a melodeon is. By definition, a melodeon is a small, reed organ with up to a five- or six-octave keyboard, usually housed in a piano-like cabinet.

The melodeon’s popularity in 19th century homes even exceeded that of the piano, which was more costly to produce and required frequent tuning. The melodeon produces its sound by drawing air in through suction produced by a foot pedal bellows, the air then passes over metal reeds, to produce specific musical notes, all without the need for tuning.

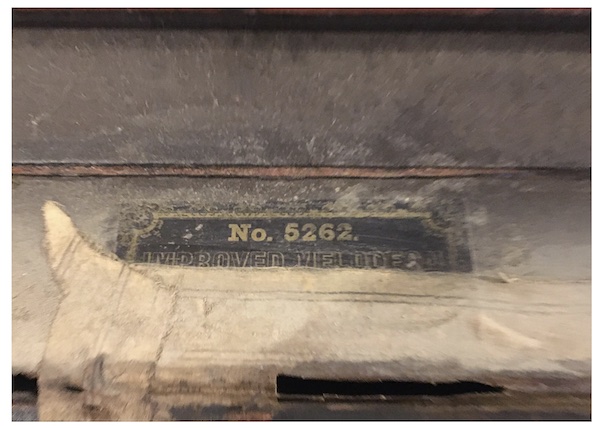

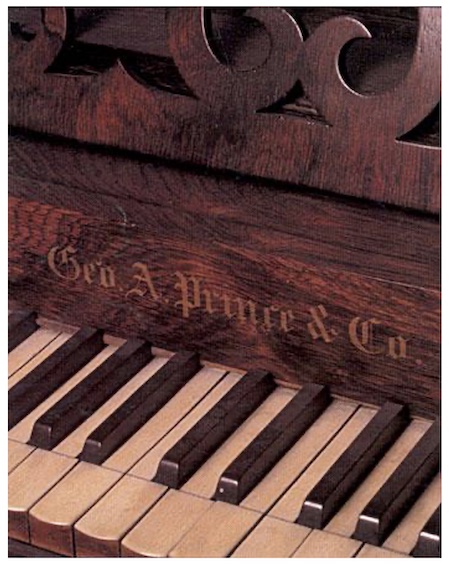

The Buffalo connection was forged through the partnership of Jeremiah Carhart and Elias Needham, working under the employ of George A. Prince & Co. Music Store at 200 Main Street, Buffalo. Their patent in 1846 solved several deficiencies found in earlier melodeon versions, hence their model became known as the “Improved Melodeon” as shown above.

The Cobblestone Universalist Church probably used an early melodeon, historically, to provide accompaniment for congregational singing. The Universalist congregation found here in the 19th century had ceased regular services in the church in the 1890s, when the parishioners moved to their new Pullman Memorial Church in Albion.

Daniel Heater of Kent donated a melodeon and stool to the Cobblestone Museum in 2010. On this instrument, players must continuously pump the right foot pedal to power the bellows while playing the keyboard. The left foot pedal is for volume control.

On some melodeons the legs are collapsible so that they could easily be moved. One local family in the past folded the legs up under their melodeon and loaded it on to their sleigh to take it to a gathering in order to have music. Unfortunately the museum’s melodeon is not currently playable, but it is still a lovely example of a popular instrument of the times and is a great addition to the museum’s collection.

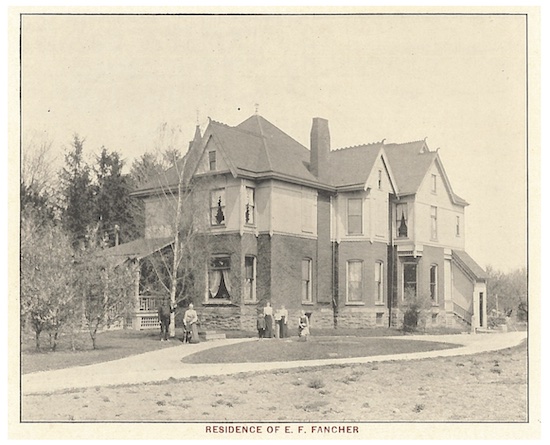

Fancher House, South Main Street, Albion, circa 1905

More recently, the Museum was fortunate to receive another, albeit smaller, melodeon that harkens back to the “Fancher House” in Albion, having been passed down from Ida Baldwin Fancher (1858-1929), wife of Rev. Edward Fancher, and then to Mrs. Archie (Irene Hayes) Fancher (1897-1940). In 2020, Sandra Fancher-Bastedo donated her Fancher family heirloom to the Museum for posterity, on behalf of her siblings, children and many extended family members.

The Fancher melodeon, stands approximately 30″ high, 30″ wide, and 14″ deep, has a four-octave range with ivory keys. The bellows are attached beneath the keyboard and are pumped using the musician’s knees instead of feet.

In his book, “Trivial Tales,” author Bill Lattin tells a story about a certain Irishman who was his great-grandfather’s tenant in 1880. Lattin knew that the Irish family was hard up and needed whatever help they could get. He approached the Poormaster and explained the family’s dire straits. (At that time, before our current Social Service system, each town selected a Poormaster who made the decisions on who in that town should receive public assistance.)

The Poormaster agreed to check in on the Irish family. A few weeks later, Lattin inquired once again of the Poormaster who offered the following reasoning for not extending public assistance to the Irish family. He said, “I went to see them, but we can’t help them, they have a melodeon in the house.”

His reasoning was, if they could afford a melodeon, they didn’t need assistance. But actually, the story just goes to show the universal appeal and affordability of the simple melodeon in the 19th century household, unlike its more expensive cousin, the piano or reed organ. The Irish family’s melodeon may well have been acquired second hand, or even been given to them at little or no cost. By 1880, reed organs were replacing the melodeon as the instrument of choice.