Historic Childs: J. Howard Pratt, esteemed local historian (Part 2)

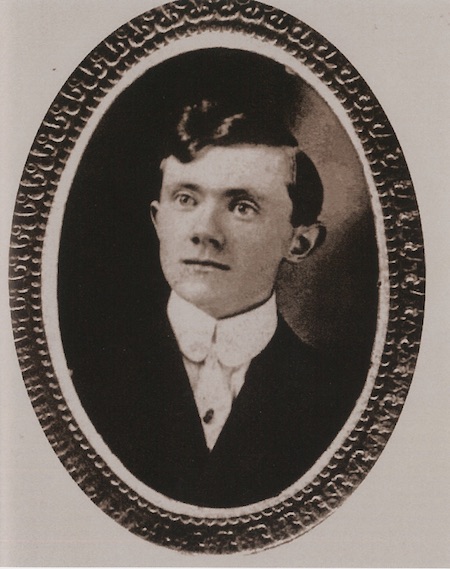

J. Howard Pratt c. 1910 – Courtesy Orleans County Historian

By Doug Farley, Cobblestone Museum Director

Vol. 2 No. 25

GAINES – This is the second article about historian J. Howard Pratt. Mr. Pratt was born on August 15, 1889. In 1980, at the age of 91, Howard sat for an audio recording session conducted by Orleans County Historical Association in 1980.

The following reminiscences have been transcribed from that session. The full audio and text file is available online.

Sickness, Quarantine and Vaccination

(As told by J. Howard Pratt – August 6, 1980.)

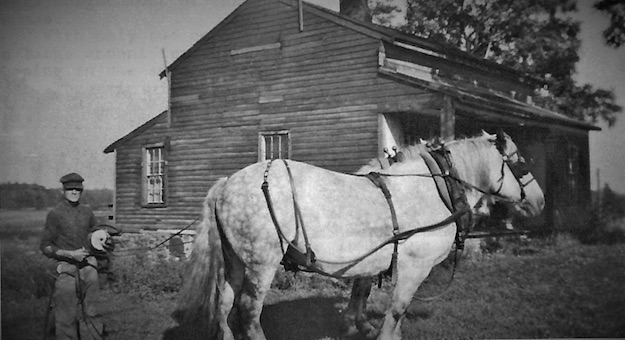

J. Howard Pratt at his family farm with his team of Percheron horses, c. 1920

Well the home today is much different and much is missing in the modern home compared to what it used to be when I was a boy. This old house was probably placed here and added to about 1845 and it’s been the home of the Pratt family, with my grandfather living and dying here, my uncle living here and I’ve been living here for 85 years; so it’s an old family home. The home is much different than today in the things that transpired within the home, too.

In the case of sickness, we had no great buildings and great hospitals to go to. The home was the hospital. It was the place where you lived and died. When you became sick, some of the family drove a horse to Gaines to get Doctor Eaman, or to Knowlesville to get a doctor from there, or from Eagle Harbor, or Waterport. All little towns had doctors in those olden days.

I’m going to take a typical case when I was sick because I remember going through all of these things: a sick boy, not too old. They sent for the doctor at Gaines, Dr. Eaman. He came and looked me all over and said, “I think Howard has got the Diphtheria.” Of course that alarmed my folks a great deal. My sister had gone to school so the doctor put a sign on the house: KEEP OUT – DIPHTHERIA. You were under quarantine and my sister could not come back from school to enter here.

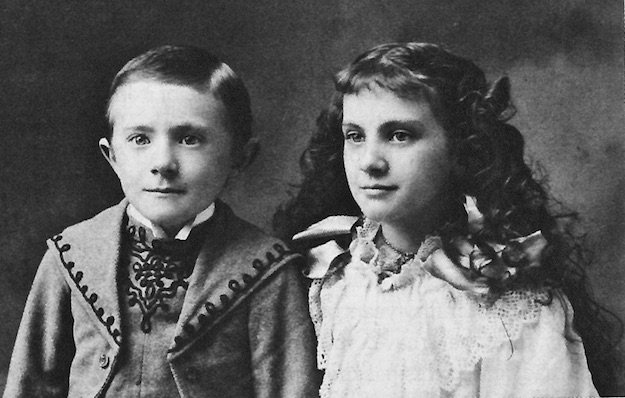

Howard Pratt age 4 and sister Florence age 9

My parents arranged with a neighbor east of us, Mrs. Warn. She agreed to care for Florence, my sister, until I was better or died. When Florence came home that evening, she couldn’t get into our house. She had to go to Mrs. Warn’s, and there she stayed over a month. Dr. Eaman was an old doctor at that time.

I can remember Dr. Earmon because he’d been here to our home several times before for different sickness. I remember he had a lot of medicine in his case. He’d give me a half a glass of water. He opened up his satchel and he took out a white powder. “Now I want a spoon,” and he put a spoonful of that white powder into the glass and stirred it up with the spoon and said, “He’s to take a teaspoon full of this every four hours.” That was my start on medicine.

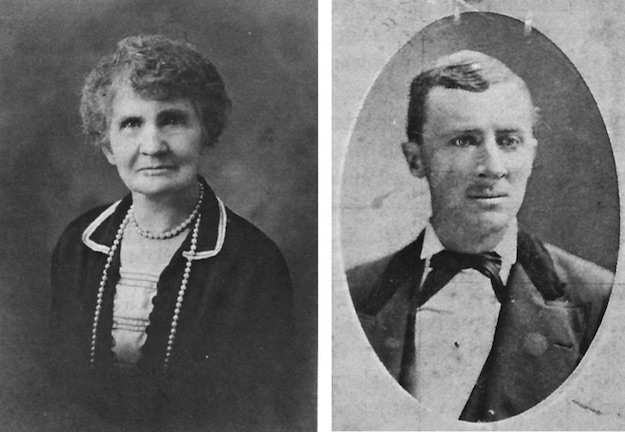

(Left) Mary Britt Pratt (J. Howard Pratt’s mother) and (Right) John Henry Pratt, father.

My folks were very alarmed over my sickness because the little girl across the road, near my age, had died within three months with Diphtheria. This alarmed my parents very much. So they hired a Practical Nurse. She was my father’s niece, Sarah Stevens who had gone from house to house; a Practical Nurse, not a Registered Nurse.

She learned it the hard way. She came and was here all the while that I was sick. She lived here and I remember one of the things she did, under the direction of the doctor: she took a newspaper, rolled it up and made a sort of a little horn. Then she put a teaspoon and a half of dry sulfur in the horn. She would hold her breath and say, “Now open your mouth.”

I would open my mouth and she would blow sulfur down my throat as I held my breath. I was not so sick that I didn’t know about what was going on. I’ll tell you, they tended to me night and day!

Someone stayed up all night. If you did not have a nurse, some of the neighbors would come in and do the night-trick, or part of the night-trick. Now after a while, I got along so they said that I was a little better and I commenced to gain and come back and I could eat more things. The doctor would come every day for a while, and then he came every other day, and at the last he would come every three or four days.

Hitching post at Cobblestone Museum

The doctor didn’t have a car. First, you drove the horse down to Gaines to call the doctor who went out and harnessed his horse. He would drive back and would tie his horse to the hitching post, and come in. I can remember several doctors tying their horses to that same hitching post. The doctor would charge two to three dollars; they were not very expensive.

After he’d been here once, if there was anybody else sick near here, he would make a circuit up this way and might go to two or three homes after leaving Gaines and traveling to the west. Then he would probably go through Knowlesville or Eagle Harbor, making a circuit and get back into Gaines, or he would go where-ever the next case called him. There was no telephone then. He couldn’t be re-directed from here by a telephone as he could in the later years. After a while I got better, the nurse was discharged and I got up. They took the sign off the house and Florence came home and we lived again as we had been living.

Many times there were lesser diseases: Whooping Cough, Measles, and things like that; colds and so on. In the case of lesser sickness, Mother was the nurse. She was the nurse for the household. She’d had lots of experience with the sickness. At that time they didn’t have as much medicine as today. The medicine you had in the home was Quinine, whiskey, hot water, and hot water bottles, Skunk’s Oil, and Mutton Tallow, which Lanolin is derived from. So when you had a cold, Mother was always on the job with something to break that cold up. We didn’t know whether it was going to be a cold or whether it was going to be the Grippe, so if they thought you were going to be real sick, or if you had any touch of fever, they would commence to load you with Quinine.

We had Quinine in bulk, a little bit of white powder. I remember Father always used to measure it out on the small blade of his jack-knife. It was bitter and we didn’t like to take it but we took it because I’d rather have the Quinine than we would being sick. Then it was followed by things that was hot, to heat you up. The older ones and even the younger children; they would take boiling hot water, as hot as you could drink, and they would put in about a tablespoon of whiskey in a whole cup of hot water, put sugar in it and then you had to drink it. You had to be in bed, and then we had hot water bottles placed around us; mostly glass fruit jars, around us with hot water. Now the idea was to get the patient to sweat. Whenever you can sweat you will break the Grippe or cold. I remember later doctors coming and giving me pills that caused me to sweat. Sometimes your undershirt would be just wringing wet.

I remember having the flu during WWI, and I remember we had Doctor Waters at that time. (Doctor) Earmon was dead, so Dr. Waters from Knowlesville came here. Tied his horse out to the hitching post and stopped on the stoop and put a handkerchief over his nostrils. It’s the only thing he could do to prevent catching the flu. He came in and he ladled out Quinine and things like that. They did not have, at that time, the medicine that would knock out the serious fevers that they have now.

When the sickness got into Pneumonia, they didn’t have anything that would knock the Pneumonia out at that time. If you got Pneumonia, your chances was only one in two or three that you would get through. That’s what the most of them died with. That’s what got the young and the old because lots of people in the 1920s died. It (flu) wasn’t a disease of the elderly people entirely; everyone had it. I can remember that when I got it, we had a new furnace just put in.

“If you got Pneumonia, your chances was only one in two or three that you would get through. That’s what the most of them died with.”

In addition to other medicine we had Skunk Oil. That was something that you would rub on. Now, that isn’t the Essence-of-Skunk that you can remember by smelling. It had no smell at all. I’ve got some here in the house if you want to try some. But that is good to rub on your chest. Mother would always put a Mustard Plaster on the chest and almost burn you to get the fire in there. I took the Skunk Oil and poured my hand full, like that, and wet my chest, just as if it was water, and rubbed it on there; got right down on my hands and knees and let the heat from the register drive it in, and when that was dry, I’d oil my chest and let it dry in; then I went to bed.

I took all the other medicine and in the morning my fever was relieved, my chest had loosened up. That was one of the things that they did. Now we didn’t have as hard a case of this old Grippe as they do now-a-days. Sometimes it was almost impossible to knock it out. But now of course they have good medicine and they will dope you with pills, even in your blood, if they want to catch you quick enough. Many of the diseases have been headed off by the doctors and their medicine.

In those days we had no vaccination for Diphtheria, not even for Smallpox. I was not vaccinated for Smallpox until I commenced teaching in 1911, and then you had to be vaccinated! And I had to keep that up when I was teaching in different places – being vaccinated every seven years. One time I was so sick with the vaccination that I had to get a substitute teacher.

Death and Funeral in the Home

(As told by J. Howard Pratt – August 6, 1980.)

All of the sicknesses didn’t come out as well as I did and oft times there were deaths in the houses. My Grandfather lived and died in this house and his funeral was here and he was buried from this house. Then, my Uncle Will lived here and he died here. Then when my father lived here, one of the maids, or the girl that worked for Mother, died here with Appendicitis. They didn’t call it Appendicitis, they called it ‘stoppage of the bowels.” Her life could have been saved if they knew what they do now about medicine and had hospitals and medicine to take care of her. Nothing seemed to help her that they gave her. They didn’t have anything that was worth anything anyway at that time.

Body Cooler in Victorian Parlor at Cobblestone Museum Ward House. Used in pre-Civil War era, prior to today’s embalming process, to chill the deceased’s body during home visitation.

So, we had many deaths. My wife’s mother died in this house. My wife died here, some eight years ago. The body of the dead was not taken from the home. The Undertaker came here and laid them out in their good clothes. You would go to McNall’s, or whoever you were going to at that time, to select your casket. The family would look them over and order the casket. The undertaker would come here and bring the casket and put the body into the casket. The casket was placed usually in the parlor, in this room here to my right. (NOTE: Mr. Pratt is sitting in his dining room).

They didn’t embalm them as they do now, but they did just a little. Of course the crepe was on the door and there was a time of mourning for the people and many people would come here and call. Usually the third day was the day of the funeral. The Undertakers would come here with a vehicle; it wasn’t a wagon but it was a big cart and they brought lots of chairs, probably 50 extra chairs. They would set them up in your home. If you had lots of room they would fill two rooms with chairs and so when the crowd came, because there usually was a crowd to country funerals, there would be seats for all. But in small houses, I’ve seen the two main rooms of the house filled up and men standing outdoors listening, especially in Mrs. Neal’s which I will mention later.

Well, the cost for the funeral was not over a quarter to what it is now. The minister came; you hired the minister that you were with from whatever church you believed in. He preached a sermon. Sometimes in the olden days they used to have singing. My father was a pretty good singer and he and Mrs. Stanley would sing at funerals and usually one song, probably three verses to the song. “Nearer My God to Thee” was one of the favorites.

The minister gave the prayers and readings from the Bible. The funerals were quite an event. The neighborhood stopped work and they all went to the home; even the men would stop work and go there. Some of them would be dressed up and some of them would be in their working clothes. But there was honor that they should go to a funeral, especially with the neighbors. The neighbors were much closer than they are today, and so they all gathered there.

Now, I want to take up the funeral of Mrs. Neal. She lived down just east of the burying ground, the Otter Creek Burying Ground, about two-tenths of a mile. You go down there and I think Hollenbeck lives there now. Mrs. Neal lived there and I remember going to that funeral because I was quite a young man at that time and the men – there were so many at the funeral that we couldn’t all go in; the men and myself stayed outside. The door was open, it was in the summertime, and we could hear a little bit of the sermon but not too much of it. But of course we knew when they got through. And then, when the funeral was ended, the hearse, which was a horse-drawn vehicle, usually with black horses, there was glass on three sides of the hearse, the back was glass, and the casket was put in the hearse.

Usually there was four pall-bearers, or six if it was a large, heavy person; but that was the usual number, and they were put into the hearse and then they would drive ahead. The minister would go first and then the hearse, and then they would stop a little bit and then the very close relatives would get into a buggy (wagon) or carriage, and they would pull up next to the hearse.

The husband or the wife, whichever one was living, and their children, and then the next nearest relatives, and then the farther relatives from there until the friends ended up the funeral procession. But they would wait until they all were loaded by stopping in the road. It’s two-tenths of a mile from where she lived, over to the burying ground and I remember distinctly that the head of the procession got over there and they were just loading up the last of the friends, showing that the procession was two-tenths of a mile long. That shows how many people went to one of these old country funerals. We thought it was necessary; we thought it was an honor to the dead and we always attended. If they were within a mile or two miles everybody went.

The neighbors would send in food during this time. Usually right after the death for a day or two, and the day of the funeral, the food was sent in. This is one of the things that we still remember about friends in the country. The family used to wear black and all the relatives wore black. If they had black dresses, they would always wear the black dresses. That was the sign of mourning. The other people wore dark clothes if they had them.