Editorial: Where is outrage over state shafting villages, towns with AIM funding?

Structural discrimination from state leads to high taxes locally, neglected infrastructure

Photo by Tom Rivers: The Village of Albion has low water pressure on the east side of the village and has put plastic bags on fire hydrants on East State Street so firefighters don’t use them. It’s part of an aging infrastructure showing lots of wear and tear.

Town and village leaders in Orleans County and across the state have failed to fight for a long overdue increase in state aid through the AIM program. They need to holler but can’t muster a whisper.

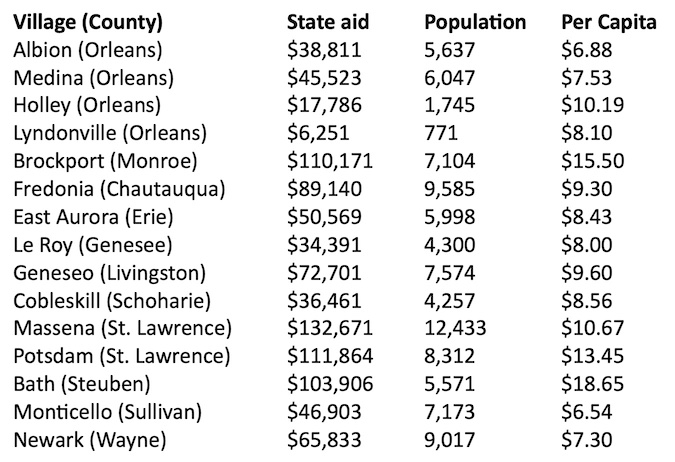

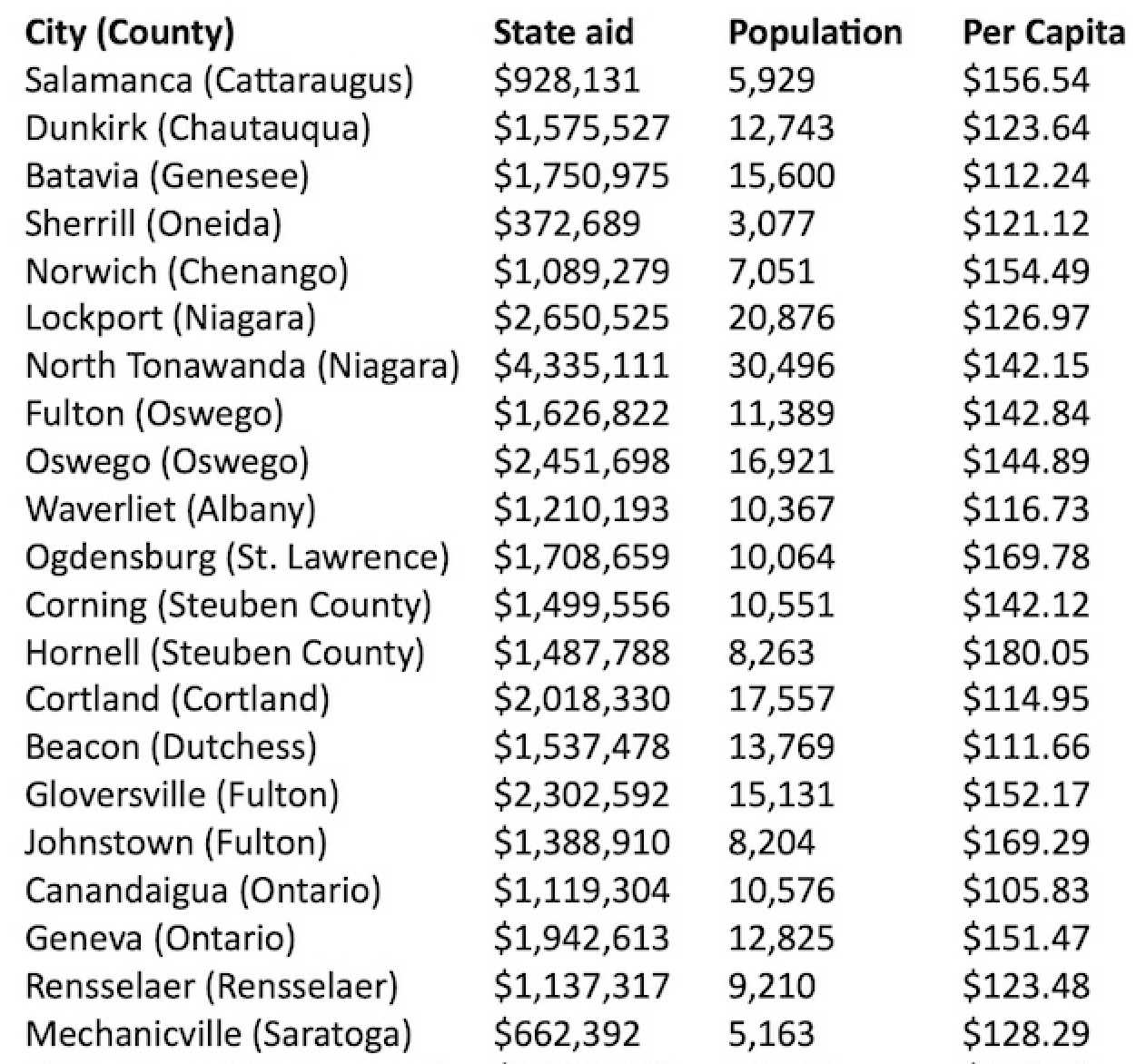

The state sets aside $715 million annually through Aid and Incentives to Municipalities (AIM). The cities get 90.5 percent of this money, with most small cities getting $100 to $150 per capita in aid.

The city of Salamanca, which is similar in size to both the villages of Medina and Albion, collects $928,131 in AIM funding or $156 per person for its 5,929 residents.

Medina, population 6,047, gets a lowly $45,523 in aid, while Albion with 5,637 residents, gets even less at $38,811. That is a meager per capita of less than $8 for Orleans County’s two largest villages.

It is infuriating to see the disparity of money given to small cities compared to similar-size villages that offer comparable services. But you don’t hear much griping from our local officials or our state representatives.

Orleans Hub calculations based on U.S. Census population statistics in 2020 and funding amounts from the NYS Division of the Budget.

I realize we are proud people who think we can manage our way out of what has turned into a crisis of high taxes and neglected infrastructure. But we need more revenue, outside of property taxes, especially for our villages.

Look at Medina facing a $1.7 million expense for a new ladder truck and an estimate of $6 million for an addition to its fire hall. Those projects will be a huge tax hit to a village that already has the highest tax rate in the Finger Lakes at $21.15 per $1,000 of assessed property.

The bond payment for the fire truck would be about $160,000 a year over 20 years. The fire hall will likely be even higher than that. And both payments are already on a strapped village where it feels the taxpayers are tapped out.

If only Medina was treated like a small city by the state with AIM. The village could easily handle those new bond payments and it’s high tax rate would be much lower.

The state started AIM in 2006 as a revenue-sharing program with cities, towns and villages. It gave the vast majority of the money to cities, which often have high poverty concentrations and greater demand for services.

The state should develop a metric that looks at poverty levels in communities, the tax burden on residents and the services offered by the municipalities. Right now, it doesn’t make much sense why there is such a disparity in the payments, and that includes among the cities where some get much more than others.

Of the $715 million in AIM, the cities get $647.1 million, while towns statewide receive $47.9 million, and villages share $19.7 million.

This money is a small chunk of what the state brings in sales tax each year and is intended to help municipalities pay for some of their critical services.

In Orleans County, the state takes in close to $25 million in sales tax with its 4 percent share, or half of the 8-cent tax on purchases.

Orleans County only gets $381,897 total in AIM funding. That is $108,371 for the four villages: Albion, $38,811; Holley, $17,786; Lyndonville, $6,251; and Medina, $45,523.

The 10 towns collectively receive $273,526, which includes Albion, $46,944; Barre, $12,486; Carlton, $13,680; Clarendon, $11,416; Gaines, $21,323; Kendall, $21,299; Murray, $44,677; Ridgeway, $46,273; Shelby, $45,007; and Yates, $10,421.

The AIM amounts haven’t increased in 15 years for anyone, even as the state budget has grown at a breakneck pace, from $132 billion in 2009-10, to $142 billion in 2013-14, to $229 billion in 2023-24, to the governor’s proposed budget for 2024-25 at $223 billion.

If state legislators and the governor don’t want to increase AIM significantly, they could first start by looking at the AIM payments to villages. Those payments could be multiplied by 10 and still be short of what small cities are getting.

A good start would be tripling the payments in the new budget. That would cost the state about another $40 million. If that happened, the Orleans County villages of Medina would get about $91,046 more, with Albion at another $77,622, Holley at $35,572 and Lyndonville at $12,502.

This wouldn’t be a transformative difference, but it would help. In Medina, for example, the village takes in $3,786,964 in property taxes. Another $91,046 in AIM would represent 2.4 percent of the tax levy.

I would focus on the villages first because they have police protection which isn’t offered by the local towns. The village police save the state (and county Sheriff’s Office) from paying more for additional officers and deputies.

The state should develop a formula for how it gives out this money, much like it does for school districts where it factors in services, enrollment or population, community wealth and several other factors. With AIM, there is no rationale for why some get much more – or less – than others.

Our elected representatives in the state government have failed us in Orleans County with this issue. They don’t speak out about such a glaring disparity in state aid to our villages and towns, compared to small cities in the state.

State Sen. Rob Ortt and Assemblyman Steve Hawley have had news conferences in the past month seeking more state funding for school districts and with CHIPS money for road paving.

These two are both articulate and forceful speakers. They should take up the cause of the gross AIM disparity for the towns and villages. I’d like to see press conferences and press releases with fiery rhetoric about this issue. They could stand outside the Medina fire hall, or by Albion’s off-limits fire hydrants.

The Albion village sign on Moore Street is in front of a fire hydrant that is bagged due to insufficient water pressure.

More state funding for the towns and villages would bring in new revenue to help knock down taxes and maintain services.

Orleans Hub has written about this issue many times in the past decade. There hasn’t been a sustained charge from our local team of officials – village, town, county and state – about how to press the state and rectify a situation where we are clearly getting shafted.

When others have faced discrimination, they have marched to help bring awareness to their plight. They have bandied together and not accepted second-class treatment.

Statewide a powerful display would be carrying a torch from one end of the state to the other, with mayors, DPW workers, police officers, clerks, firefighters and residents of villages and towns walking together, and then handing off the torch to the next town.

It should be delivered in the state capital with a massive rally of our small-town people, showing the Legislature and governor that there is work being done at all levels of government, not just cities. There are poor people and middle-class residents in towns and villages, too, who could use a break in their property taxes if more AIM came to their town or village. Our DPW could use updated plow trucks, rather than vehicles more than 20 years old.

Our firefighters would welcome dependable fire trucks that aren’t nearly 30 years old. They should be able to use fire hydrants that spew out a powerful stream of water, rather than a trickle.

I realize a statewide effort would be hard to coordinate. Orleans County could be the leader. I’d like to see Orleans municipalities and their elected officials, employees and residents have a march from one end of the county to the other, going 25 miles along Route 31, or 104 or the towpath.

I don’t understand the meekness with the issue. Our small towns and villages should follow the example of Rosa Parks, who refused to go to the back of the bus.