During WWI, Medina’s Patriotic Committee on Home Gardens urged backyards for veggies

By Catherine Cooper, Orleans County Historian

“Illuminating Orleans” – Volume 4, No. 15

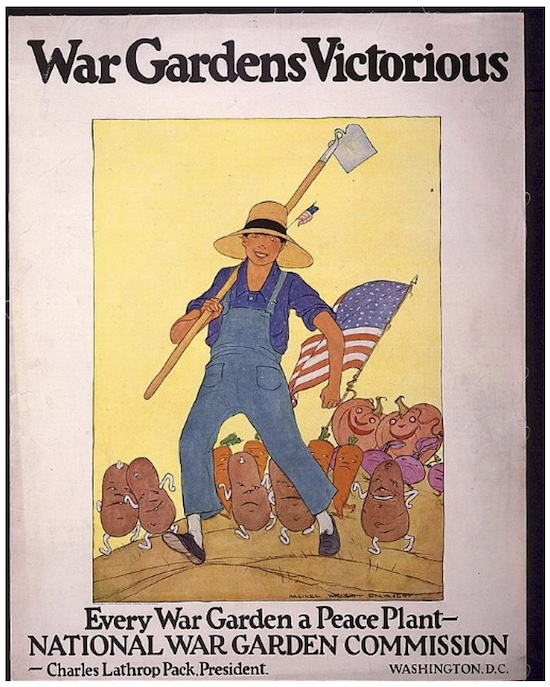

This 1919 poster depicts a boy with a hoe leading a parade of “smiling” vegetables displaying an American flag. (Maginel Wright Enright, Library of Congress collection)

“I hereby declare and set aside Friday, May 11, as Garden Day, and urge all citizens to observe the same by putting in a home garden on said day.”

This declaration was made on May 9, 1917, by Dr. Warren E. Stocking, acting president, and subsequent mayor of the Village of Medina.

A poor harvest in 1917, the loss of agricultural workers due to military conscription, the sabotage of ships carrying food supplies, and the necessity of supplying food to soldiers, led to a food crisis for the Allied forces.

The U.S. Food Administration was established in 1917 to produce and conserve food for American and Allied troops as well as for war-torn Europeans. With slogans such as “Every War Garden a Peace Plant,” Americans were encouraged to plant “home gardens” or “liberty gardens” during World War I. These were the forerunners of the “victory gardens” of World War II. Food production and conservation were linked to patriotism.

This poster created in 1918 by William McKee evokes the iconic Spirit of ’76. Wheat and vegetables replace the fife and drum. (Library of Congress collection)

In Medina, the Patriotic Committee on Home Gardens started a campaign in April 1917 to make every backyard in Medina a participant vegetable producer.

“The importance of this phase of war activity cannot be overestimated, as every family that provides itself, not only helps to bring down the cost of living, but also sets free for war uses much-needed foodstuffs, and a planter has come to occupy a place of importance in war secondary only to the soldier himself.” (Medina Daily Journal, April 25, 1917)

Committee members included Parke Davis, William U. Lee, Harry W. Robbins, Fred B. Howell, Robert H. Newell, Mrs. David White and Mrs. Eugene Walsh.

The committee campaigned to have every back yard in Medina produce vegetables for the home. Instructional leaflets provided by the Garden Club of America were distributed to schools and factories.

Students were encouraged to encourage their parents to participate. The Lyndonville Enterprise in 1918 proclaimed that “Every boy and girl that helps with the garden is helping win the war.”

The instructional leaflets outlined how best to use a plot of 20 by 30 feet for a succession of spring, summer and fall crops and how the suggested vegetables should be cultivated. It was estimated that working one hour a day on a 20 x 20 ft. plot would provide vegetables for a family of six. Sensibly, the Committee also arranged for the services of a horse and plow and an experienced plowman at a reasonable cost.

The Committee was “besieged by orders.” By May, it had received enough orders for seed potatoes to warrant ordering “a car of Maine potatoes.”

Nationally, the campaign was a success. Home gardens produced around 1.45 million quarts of canned fruit and vegetables, food which critically helped avoid starvation in Europe during the final two years of the war.