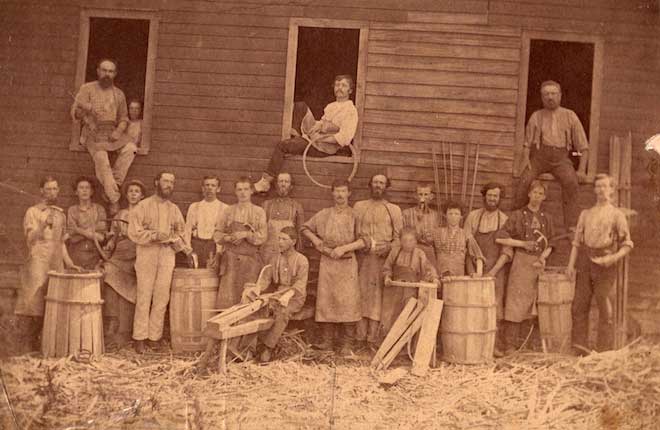

Coopers, who were skilled in making barrels, played essential role in local agriculture

Cooperage of Charles Bennett at Eagle Harbor c. 1880

“Overlooked Orleans” – Vol. 4, No. 20

When reflecting upon the various skills and trades that once existed in this area, it is amazing to see how much society has changed. We no longer rely upon the chair caner, the cobbler, or the blacksmith to produce the items we so easily purchase from the nearby department store. Yet a series of articles in 2015 indicated that the resurging bourbon industry could potentially lead to a barrel shortage and the need for coopers to produce the casks required for storing alcohol, so perhaps not all of these “ancient” trades have disappeared.

The production of barrels was significant to the establishment of Orleans County, not as a direct result of barrel construction but as a byproduct of the need for staves. Arad Thomas mentions the production and shipment of staves on several occasions in his book Pioneer History of Orleans County, New York. His most detailed account relates to James Mather of Gaines, who exchanged needed resources and tools with settlers for staves. The staves were then sent to the mouth of the Oak Orchard or Genesee River and shipped to Montreal where tools and resources were sent in return. Isaac Signor notes the significance of stave production to the development of numerous areas throughout Orleans County, calling attention to a sizable stave manufacturing operation established by Charles Simmonds on Church Street in Medina around 1859.

This particular picture shows a cooperage operated by Charles Bennett sometime around 1880 at Eagle Harbor. Based on information recorded on the reverse of the image, the outfit stood on the south side of the Erie Canal near the bridge. An 1875 map of Eagle Harbor shows a building labeled as C. Bennett & Co. near the south edge of the Canal just east of Eagle Harbor Road, but we also see a cooper shop marked at the end of Midway Road on the north side of the Canal. Standing on the far left is Henry Fountain, with C. Bennett sitting in the left window and Charles Bennett standing fourth from left with what appears to be a book in hand. This would indicate that Charles was in charge of this particular operation as the other men are standing with tools in hand.

One particular point worth drawing attention to is the span of ages present in the photograph. Older men appear alongside boys as an indication of how the trade was carried on over the years. Young men started their work as apprentices and learned the nuances of the profession from the journeymen and master coopers who, for some, had practiced the trade for decades. I often think back to the stories of my Great Grandfather, George Henry Ballard, who worked for Duffy Mott in Hamlin, NY as a barrel cooper. As a young man, he learned the trade by working with his father, Charles Ballard, who in turn had learned the trade from his step-father, Mortimer Clark. For some of the men, the profession was one filled with uncertainty as the ebb and flow of growing seasons could create a dearth of work at times.

Much can be said about the complexities of what seems like a fairly straightforward process, yet the trade of the cooper was one marked by precision and attention to detail. A cooper was not simply a cooper, as some specialized as “white coopers” or those who manufactured churns and pails, others specialized as “slack coopers” who manufactured barrels for dry goods such as grain and flour, and others specialized as “tight coopers” who produced barrels for storing oil, molasses, and alcohol. Each specialty required a familiarity with particular types of wood and processes for preparing the staves for assembly. As an example, the wet cooper produced barrels using staves cut from straight grain green wood, which would bend far easier and was resistant to rotting.

The men at this cooperage were slack coopers, preparing barrels for the shipment of agricultural products such as apples and grains. Perhaps one of the best features of this image is that it showcases the various stages of barrel making, though I would venture a guess and say that was not the intention. First the staves were cut with a drawknife and axe, and then allowed to dry to prevent shrinking after the barrel was assembled. Although some coopers performed this work, many farmers chose to produce staves and sell them to the cooper as a means for reducing the costs associated with purchasing barrels.

The cooper then used a shingle horse or shaving horse to carefully shave appropriate tapers and bevels to each stave. A young man sits near the center on a shaving horse and appears to be working with a stave. A stave with a larger taper resulted in a barrel with a larger bulge in the center, which was far stronger and fit for storing wet goods. The staves were set in a truss hoop at the bottom, as seen by the young boy standing five in from the right, and placed over a blazing fire to allow the staves to bend. The barrel staves were then drawn together using a cooper’s windlass and hoops were hammered into place using a hoop driver. Barrels for storing dry goods were manufactured using birch or cedar hoops as opposed to metal hoops.

After the hoops were set, the cooper trimmed the staves to equal length with a hand adze, the tool that looks like a hammer with a curved end, and the man standing in the center holds a sun plane that was used to smooth out the ends of the staves. A croze was used to cut a groove around the top and bottom of the barrel so that the barrel head could be installed.

The production of barrels was a time consuming process, one that required hours of physical labor and a well-trained eye. The piles of wood shavings strewn across the ground in this image show how much preparation was required before assembly of the barrels. The tattered leather aprons demonstrate the ongoing use of fire to bend and craft the curves within each barrel and the extensive number of men standing in front of the cooperage shows the significance of the barrel to agriculture in Orleans County.