Lydia Johnson of Lyndonville was only nurse from Orleans County to serve in Civil War

By Catherine Cooper, Orleans County Historian

Illuminating Orleans – Vol. 2, No. 18

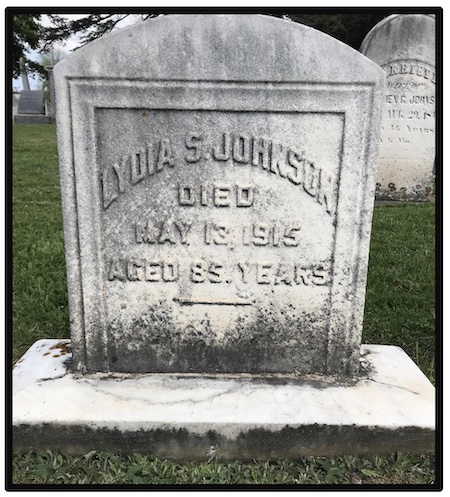

The headstone for “Aunt Selina” as she was known is in Lynhaven Cemetery in Lyndonville.

LYNDONVILLE – Lydia Selina Johnson of Lyndonville was the only nurse from Orleans County to serve in the U.S. Civil War. She was born on April 31, 1830, the daughter of Stephen Burr Johnson and Maria (Gilbert), the youngest of five children.

The following is an excerpt from a reading given by Selina Johnson at the Literary & Historical Society of Lyndonville, Feb. 22, 1898. Full text on file at the Orleans County Historian’s Office.

“Let me relate to you an incident that I witnessed in the Old Warehouse Hotel, in Georgetown, in the Fall of ’62, just after the second Bull Run Battle: there had been a soldier boy who had just passed his eighteenth birthday, by the name of Shepherd from Marble Head, Mass. brought in there after having lain in the battle field eight days.

“The surgeons, upon examining the wound, found that the leg was so badly shattered that it would have to be taken off at the knee. He stood the amputation well, but it was only a short time after, before it was discovered that tetanus had set in, and in about two days, the flesh had drawn back, so that the end of the bone protruded nearly an inch.

“It was decided that his only chance of life was to have the bone cut off so the flesh could be brought up and cover the end of it. They tried it, but it was not of any use…He was a terrible sufferer the last few days he lived. The only way he could get any relief from the fearful pain was for someone to clasp around the leg with both hands, as near where it was cut off as they could and while clasping tight, press the flesh down over the end of the bone. It was very hard work, so we nurses took turns.”

With the advent of the war, reformer Dorothea Dix had been assigned to organize a female volunteer nurse corps. The requirements were strict. Candidates were to be matronly persons of experience, good conduct, or superior education and serious disposition, who displayed habits of neatness, order, sobriety, and industry.

These criteria were designed to minimize potential problems or complaints as female nurses were not welcomed by the male medical establishment at first. Compensation for nurses was 40 cents a day and a three-month minimum period of service was required. As the war progressed, the nurses proved invaluable as caretakers in a sea of carnage, providing nurturing comfort and assurance to injured and dying soldiers, as well as medical care.

The disorganization during the early months of the war has been chronicled. Selina’s first experiences of those early months echoes those accounts. She described this to her audience in Lyndonville on that February evening in 1898:

“The Government was not prepared for such manslaughter. Hotels, schoolhouses, churches, and private homes were commandeered for hospital use. The Capitol building was full and there were 500 in the Patent Office Building. In the winter of 62 and 63, there were no less than 12,000 sick and wounded soldiers in the District of Columbia. If you counted those in and around Alexandria, you would have to multiply that number by two. Our Government was without the means to do with and they were ignorant of the needs of so many. They had to learn by experience. We lacked help and almost everything else but bread. Long weary tramps going from one Sanitary Commission house to another, sometimes getting the desired articles and at others, going home empty handed.”

The situation improved as time went by:

“During the winter of ’64 and ’65, I was in the Chesapeake Hospital, Fortress Monroe. At the time, everything was running like clockwork. Order had been brought out of chaos. There was plenty of everything and if we wanted anything, we knew where to get it.”

Selina’s account of her experiences is detailed and forthright. She describes the sufferings of the patients and the privations of the hospital conditions. Simple things made such a difference – wooden stools to sit on, tinware with handles for cooking. A dying soldier expressed a desire for new milk before it got cold with some bread in it, like his mother would give him. A kind lady who kept a cow brought him fresh milk morning and evening for the remaining week that he lived. This is but one of her graphic descriptions.

Following the Civil War, deceased soldiers’ widows, dependent fathers, and brothers were eligible for pensions. The Grand Army of the Republic, a veterans’ organization, waged a long campaign for the Dependents’ Pension Bill, which was approved in 1890. This expanded pension eligibility to include disabled veterans who had served for ninety days, or widows whose husbands had served for ninety days, regardless of whether the disability or death were service connected. Funding for the expanded benefits accounted for roughly 40% of the federal budget at that time.

However, nurses who had served in the Civil War were not automatically entitled to any post war service benefit and had to wage a long campaign until the Army Nurses Pension Act was finally passed in 1892. This entitled women who served as nurses in the Union Army to a pension of $12 per month, provided they had worked at least six months and had been hired by someone authorized by the War Department to engage nurses. This was a departure from previous legislation as it was not tied in with a woman’s marital status, but rather, was a recognition of her contribution. It afforded a welcome degree of financial independence to many women.

Selina returned to Lyndonville after the war. She did not marry, she worked at her brother’s office, lived with her widowed mother until her mother’s death and subsequently lived alone. She was able to enjoy her nurses’ pension for twenty-three years. According to her obituary printed in the Lyndonville Enterprise of May 20, 1915, she was the primary founder of the Literary and Historical Society of Lyndonville and was a member of the Methodist Episcopal Church. She died at the age of 85 at the home of her niece, Mrs. Bessie Johnson, on North Main Street, Lyndonville. The Sons of the Veterans conducted military honors at her graveside in Lynhaven Cemetery.