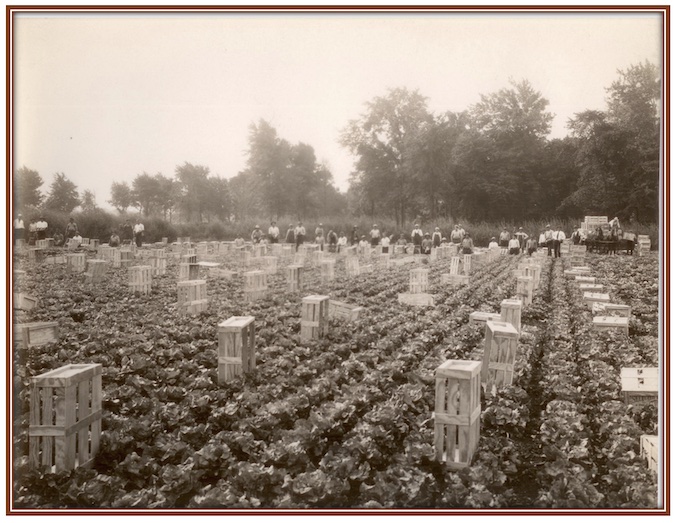

Mucklands proved highly productive, but not without a lot of work

Photo by Fred Holt of Albion – Lettuce is harvested on the mucklands in the 1930s.

By Catherine Cooper, Orleans County Historian

Illuminating Orleans – Vol. 2, No. 17

In 1936, the Calarco brothers set a record for raising lettuce: 108,000 heads from three acres. In March of 1977, The Journal-Register noted that crops growing in the rich soil brought in about $7 million a year.

Mother Nature was not always kind. A windstorm in June 1926 and a hailstorm in July 1947 were but two of several weather-related setbacks experienced. Flooding was a recurrent problem.

Heavy rains in September of 1977 (7.28 inches, three times more than the monthly average of 2.37 inches) caused massive crop destruction. As a result of lobbying efforts, the Oak Orchard Small Watershed Protection District was formed whereby the Federal Government assumed all construction costs for a flood protection plan, while owners were responsible for maintenance and replacement costs. The project began in 1982. Erosion has continued to be a problem; some estimates indicate that a third of the original area has been lost.

Though many of the tasks associated with the large-scale crop production on the mucklands were mechanized, some, such as weeding, thinning, and harvesting still required labor intensive manual labor. Those who “worked on the muck” remember their experiences vividly. It was hard work. Hard on the knees, the back, the hands and the hours were long.

Ciel White of Medina recounted her experiences in an oral history interview conducted in 1982. Her mother and many other women “the wives of Italian and Polish families” worked on the muck in the early years.

Born in 1911, Ciel was only 7 when she started to accompany her mother to work during the summer and on Saturdays throughout the school year. Farmers provided transportation. In the spring, they worked on weeding the onions and carrots to help the crops thrive because “the weeds grew as fast as whatever was planted.” Hand weeding was necessary because the young plants were delicate. Lettuce was thinned after it reached a certain height.

Ciel recalled: “When you were weeding, you got paid by the day… which was from 7:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. The women got $1.50 a day, but the kids only got $1.00.

You would have an hour for lunch, you would bring your own. There was a well which they had dug so you could get water. There would be a pail there and a dipper, and everyone helped themselves. And a privy.”

When they were harvesting onions:

“Each person would take two rows, the rows were about a quarter of a mile long, and there would be two people. We would grab the tops of the onions, pull them out and put them in a single row between us, so that they could dry out. Once the managers determined the onions were ready, we would go back with a crate, two people would work with the one crate and we would get 10 cents per crate.”

Ciel often worked with her cousin, Pauline Cichocki:

“After we had filled a hundred crates, we would call it a day, which was $5 for each of us. Then we’d goof off for a little bit or help our parents so that they could earn some more money (depending on how we felt).

This was also true of the carrots which was the last crop that we finished on the muck in the fall. Sometimes we couldn’t go out early because there would be frost on the tops, then as it began to warm up, they thawed out a little bit. You really got wet, because it was late in the season, and you got heavy dews as well as frost. You wore gloves, because not only had you to pull the carrots out of the ground, but you had to wring the tops off them and put them in the crate, 10 cents a crate also.”

Their work clothing was practical:

“We wore bloomers, very full pant-like affairs that came down to the knees, with elastic, and a middy blouse and a sweater. And I can remember the black-ribbed stockings and laced shoes, they were high-topped shoes, ankle supporting. You had to put pads on your knee, or they would be raw. The women would make the pads that they would put in their stockings – several layers of flannel or soft material which acted as a cushion, so that the wood and muck wouldn’t go through and ruin your knees.

In the summertime, when it was unbearably hot with the sun reflecting off that black dirt, we used to wear wide- brimmed hats. When the wind would blow, it was terrible, the dust would get in your eyes.”

Nevertheless, she recalled that morale was good, the women would sing as they worked, Polish hymns and songs. They were working for extra money for their families. Ciel’s father worked for Wm. J. Gallagher and her mother put their muckland earnings in the family “kitty.” They had bought a home, 574 East Ave. in Medina, and were determined to pay off the mortgage.

Writing from Virginia recently, Jack Capurso, formerly of Albion, recalled working on the mucklands as a teenager for three summers, 1956-58.

“As I pulled weeds out of the onions, I remember marveling that most of what we would call dirt was actually small pieces of decayed wood mixed in with soil.

The work was physically demanding, ten hours a day, six days a week at the rate of 50 cents an hour ($5.14 approx., per inflation calculator). However, after three summers I had saved almost $1,000 ($10,300 in current value) towards my first year at Geneseo.

I remember vividly 26 July 1956, the day the Andrea Doria sank in The Atlantic. We watched film of the sinking while we were having lunch. I did my best to explain to the workers what was happening but at that time my Spanish was terrible, and their English was worse. I still remember the Puerto Rican workers and wonder what happened to them.

When I come to Albion this summer to visit relatives and friends, I am going to try to find my way back to the muck. I know the memories will return, and I will smile.”

Two books on local agriculture are available at the NIOGA libraries:

• Farm Hands: Hard Work and Hard Lessons from Western New York Fields by Tom Rivers, 2010

• Mom & Pop Farming in Orleans County, New York by Canham & Canham, 2016