Medina resident, a Russian expert, was in demand for lectures more than a century ago

By Catherine Cooper, Orleans County Historian

Illuminating Orleans – Vol. 2, No. 10

Though he wrote and lectured on Russia a century ago, George Kennan’s observations on Russia have an eerie familiarity today. Born in Norwalk, Ohio, in 1848, he became adept at using the cutting-edge technology of the day: the telegraph.

He was a military telegrapher during the Civil War and soon was assistant chief operator for the Western Union in Cincinnati, Ohio. Yearning for travel and adventure, he eagerly pursued a Western Union opportunity to participate in a plan to connect communication between Europe and America by means of an overland cable route through British Columbia, the Behring Straits, Siberia and Russia. In 1865, Kennan was hired by the Russian-American Telegraph Company to travel to Siberia as part of a team to survey the land for stringing a cable.

A remote and vast area, Siberia presented many challenges. The group traveled on whaleboats, horses, rafts, dog sleds and reindeer sleds, had hair-raising brushes with death along precipices, became acquainted with nomadic tribes – the surly Chookchees and the more pleasant Koraks.

The hardy travelers ate manyalla, a staple tribal food made of clotted blood, tallow, half-digested moss taken from the stomach of a reindeer. They sampled alcohol made from fermented toadstools. They dressed in layers of clothing made of reindeer skin, they slept in yurts and outdoors, built fires from trailing pine, and survived a minus 68 degrees below zero night.

Upon his return, Kennan wrote a vivid account of his many adventures in Tent Life in Siberia. Having been smitten by the “travel-bug,” he vowed to return to Russia. Availing of his treasure trove of colorful travel tales, he embarked on a series of lecture tours to raise money for a second trip and in 1879, he set off for the Caucuses, a remote and mountainous region between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea.

Kennan explored this region at a critical time in its history. Russia had gradually asserted its power over the area throughout the 18th century but in name only as its highhanded treatment and insensitivity to ethnic allegiances created a simmering hostility. It was home to a myriad of fiercely independent khanates and kingdoms whose ethnic distinctions were reflected in the 40 different dialects spoken.

Kennan learned about the intricacies of the “adat” and the “gortse,” the customary laws of honor killing. He described his guide, Akhmet, as “a tenth century barbarian.” Akhmet had killed at least fourteen men and he was amazed that Kennan had never killed, gone on raids, protected his cattle or avenged blood. In Akhmet’s opinion: “Humph! Yours must be a sheep’s life.”

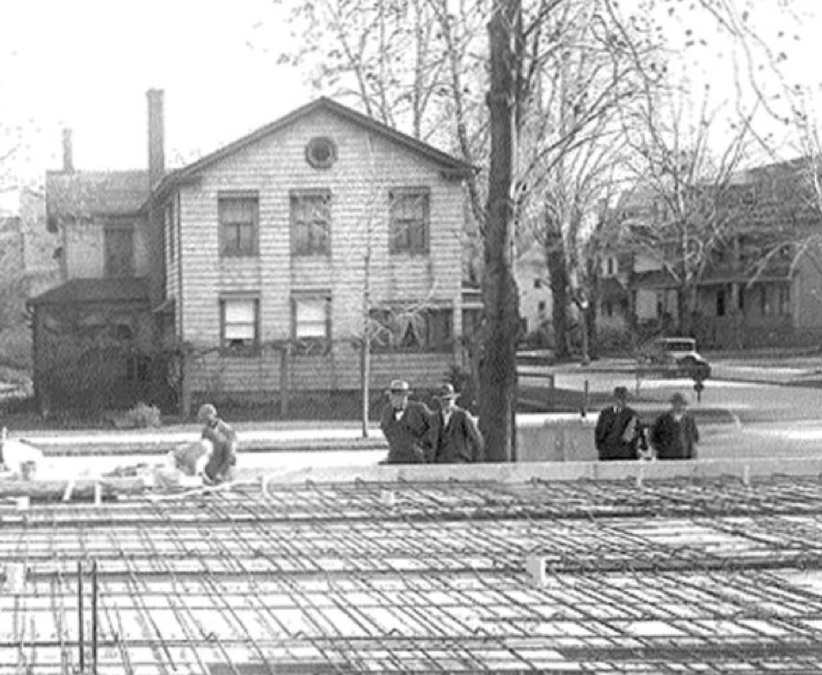

Welkenna, the home of George and Emeline Weld Kennan, is shown from a photograph taken during the construction of the Medina Post Office in 1932.

Upon his return “penniless but happy,” Kennan compiled his journal adventures in his next book, Vagabond Life. It was at this point that he connected with Medina. His brother, John, a cashier at the Union Bank, secured a job for him. George boarded with John at 200 West Center St., and fell in love with Miss Emeline Weld, who lived just across the street. They married and moved to Washington D.C. where Kennan was hired by the Associated Press, but they maintained the family home in Medina and returned frequently.

Kennan’s travels in Russia had left him with a largely favorable impression of the government. The Russian practice of using exile to Siberia as punishment was long established but had increased after the assassination of Tsar Alexander II in 1881. Tales of extreme cruelty filtered through to the West.

In 1885 Kennan signed a contract with Century Magazine for a series of articles on the exile system. Accompanied by artist George Frost, they set out optimistically, but soon encountered scenes of despair. Every subsequent prison visit and conversation left them harrowed and in despair. Kennan’s opinion changed, he concluded that the Russian system of exile was “one of the darkest blots on the civilization of the nineteenth century.”

He wrote about his experiences in Siberia and the Exile System which was translated into 19 languages. He lectured extensively, advised government officials, and effectively caused a shift in opinion regarding the tsarist regime. He was the recognized expert on Russian issues for many years. He returned to Russia in 1901 but was expelled immediately. He believed that the overthrow of the tsarist regime was inevitable. He disliked Lenin and feared his extremism.

By 1920 he had to accept that the Bolsheviks were firmly in power. In an article first published in the Medina Tribune, July 12, 1923, he wrote:

“Let no one be deceived. The Russian Leopard has not changed its spots. The first essentials of Republican institutions are freedom of elections, freedom of assembly and freedom of the press, and these things the new Bolshevist “constitution” does not guarantee – or even promise.”

George Kennan died at his West Center St. home on May 15, 1924. Emeline passed away on May 28, 1940. They are buried at Boxwood Cemetery.

(Diplomat George Frost Kennan (1904-2005) was a cousin. They shared a birth month and date – Feb. 16 – as well as a passionate interest in Russia. Both wrote and lectured on Russian affairs and ironically, both were expelled from Russia by the governments of their time.)