Historic Childs: The Erie Canal in the Town of Gaines, Part 1

Gaines has northernmost point of canal, a private bridge, turn basin and lift bridge

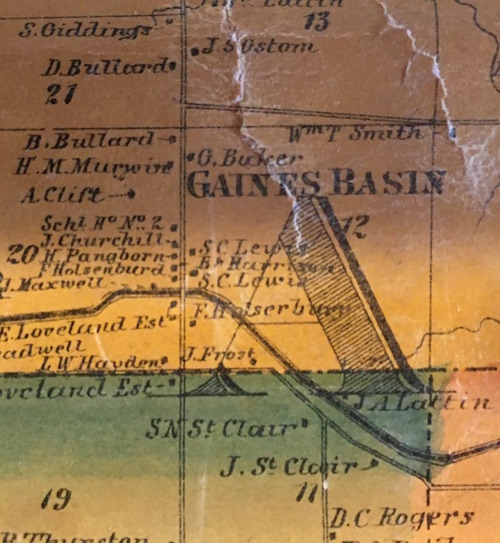

Gaines Basin, 1860 map

By Doug Farley, Cobblestone Museum Director

GAINES – Today, a quick blink is all it would take to completely miss the Hamlet of Gaines Basin located just a few miles southwest of Childs. Other than its 1832 Cobblestone School, the current Gaines Basin ghost town nestled on the towpath of the Erie Canal no longer gives a hint of the bustling canal commerce that took place there once the canal was completed.

Gaines Basin Road that bisects the hamlet, was actually the shortest distance between the Ridge Road and the Erie Canal, a fact that obviously added to the strategic commercial value of the small community that grew up on the banks of the canal. Even the name “Gaines Basin,” is attributed to the hamlet’s early ties to the Erie Canal.

At one time, after the construction of the canal, Gaines Basin could boast almost a dozen residences and at least two thriving businesses. While most of the residences were associated with farm owners, the businesses included a blacksmith shop and grain warehouse.

The blacksmith shop, present in the 1830s, was gone by the 1870s. In that time, it served the local farmers from Gaines Basin. One item produced in the blacksmith shop that remains today is an artifact called a “peel,” shown above. For those unaccustomed to the term, as I was, a peel is a shovel-like tool that is used to slide out embers from a brick bake oven. This particular peel, produced in the blacksmith shop in Gaines Basin in 1823, is part of the collection of retired Orleans County Historian Bill Lattin.

Another Gaines Basin business that came and left without a trace was a grain warehouse, also located on the north bank of the canal. It’s location on the canal made it an ideal spot to load and unload grain from a canal boat into the grain bins. While the buildings themselves may be gone, the stories of what went on there still persist.

Bill Lattin explains that his great-grandfather, Bartlett Lattin, sold grain to the owner of the warehouse around 1870. Unfortunately, he never received payment. When Lattin approached the grain warehouse owner, he said he couldn’t pay him, but offered Lattin a percussion muzzleloader flintlock rifle as a substitute for cash.

Bartlett took the gun as payment, and Bill Lattin, through inheritance, now has this artifact in his personal collection. The rifle reaches nearly 6-1/2 feet in length. Bill recalls a childhood story he was told that the early colonists often traded with the Native Americans, offering rifles in exchange for fur belts. The colonists would set the rifle on the ground and the Native Americans would stack fur pelts next to it until the pile reached the top of the gun barrel. As time went on, it was said the colonists tricked the Native Peoples by increasing the length of the barrel to garner more fur belts in exchange for a single rifle.

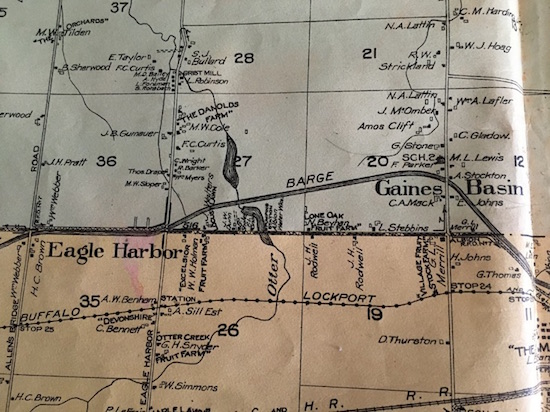

Barge Canal route, Gaines Basin & Eagle Harbor, 1913 map

The Erie Canal, even though it doesn’t occupy much real estate in the Town of Gaines, has been a big part of the community’s history. The canal stretches just a few miles from Gaines Basin to Eagle Harbor, which is another community that owes its name and existence to the construction of the Erie Canal.

It is said that an eagle’s nest was spotted in the area in 1815 at the time of the initial canal survey – hence the name Eagle Harbor. The portion of the Erie Canal situated in Gaines seems an anomaly today as we consider the canal route. Why would canal planners deviate from their southern route and move northward into Gaines? The canal, most likely, would not have passed through Gaines without a decision to put a bend in the proposed canal and move its course substantially northward into Gaines. This can be seen by looking at the map above map and noticing that the canal makes what looks like a northward detour from its course further south, to reach into a small sliver of the Town of Gaines along the town’s southern boundary.

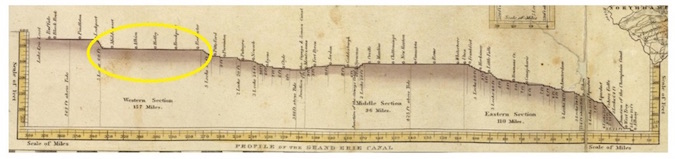

Profile Map of the original Erie Canal, 1825, Long Level highlighted

Looking for an answer to this paradox we have to consider the lack of engineering skills in the 1800s when the canal was constructed. (There wasn’t even a single engineering school in NYS at that time.) The course of the canal from Lockport east to Rochester is part of what was originally called the “long level.”

This roughly 60-mile stretch was the longest section of the canal that contained no locks to handle changes in elevation related to topography. The reason for that was in the 1800s when the canal commissioners laid out the eventual path for the canal, they discovered that there was no suitable body of water between Lockport and Rochester from which additional water could be added to the canal.

That fact meant that the water in the canal had to flow completely by gravity through the 60-mile long level from its Lake Erie headwater at Lockport to the Genesee River at Rochester where more water could be added. We all know that water doesn’t flow uphill. The bend in the canal into the Town of Gaines was created by a need to bypass higher ground further south that would have prevented the free flow of water without moving an exorbitant amount of earth.

Northernmost point on the Erie Canal, Cobblestone District #2 Schoolhouse in background

This northern route gave Gaines the distinction of containing the northernmost point along the entire route of the 363-mile Erie Canal. A state marker on the canal marks the spot, now.

Another anomaly regarding the Erie Canal in the Town of Gaines is the presence of a turn basin, shown on the map above, about half way between Gaines Basin and Eagle Harbor on the south side of the canal. The original Erie Canal was carved into the countryside with a depth of only 4 feet and a width of 40 feet.

To save construction cost, the canal was built with a single towpath servicing mules and horses pulling both eastbound and westbound boats. This fact created a dilemma when oncoming boats would meet in any spot along the canal and pass each other without tangling lines. One boat would move to the far side of the canal as its mules halted on the outside of the towpath.

The towline which was 100 to 150 feet long would go slack and sink to the bottom of the canal so the overtaking or oncoming boat could pass over it freely. When this simple method didn’t work out, the mule tenders or “hoggees” would carry the lines over the other mule team. Crew members on deck would do the same with the towrope passing over the idled boat.

Canal Turn Basin, Town of Gaines, 2021, Canal partially drained

To facilitate this process, a small number of turn basins or “wide-waters” were cut into the side of the canal to provide a safe harbor for boats that needed to “pull over,” to make repairs or get out of the way of oncoming traffic. It also served to provide a location with sufficient width where boats could be turned in the opposite direction if needed.

If a boat moved into a turn basin, it could sit there for an extended period of time, out of the way of two-way traffic moving on the canal. Also, over time, boats became larger trying to squeeze as much precious cargo on deck as possible. This scenario would create plenty of bottlenecks without an occasional turn basin to assist.

Another part of our shared Erie Canal history concerns canal bridges. From our childhood, we probably recall singing “Low bridge, everybody down. Low bridge, for we’re comin’ to a town.”

Bridges were a real sore point for canal planners. They knew that a 363-mile ribbon of water would necessitate dividing a lot of farms and property. Farmers still needed a way to access their fields on the other side of the canal. In 1817, after canal construction began, literally hundreds of bridges were needed across the state in very short order.

A workforce of state officials quickly approached every property owner along the proposed route of the canal and worked to find a solution that would allow the state to acquire the necessary land from the property owners to construct the canal. Often times, it came down to an offer to build a bridge for a farmer who may need it to reach their barn or farm land on the opposite side of “Clinton’s Ditch.”

The cost of all of these bridges was another major concern. NYS had allocated $5 million for the canal project and they needed to try to contain their costs, so the bridges needed to be as low-cost as possible. (Canal costs eventually spiked to $7 million at the time of its completion.) Saving money usually meant sticking with a very low bridge built right from ground level, instead of raising the bridge up by building abutments or other superstructures.

Lattin Bridge today

Town of Gaines property owners along the canal were “given” bridges in exchange for their signature on easements or deeds. One case in point was the farm of Lansing Bailey. In the 1820s during canal construction, a bridge was created to accommodate his farm house in the Town of Albion and farm land in the Town of Gaines. In 1837 the farm and bridge passed into the possession of Joseph Lattin. The “Lattin Bridge” as it became known, was built ostensibly to service one farm. In the late 1880s, the bridge began to service traffic going to and from the Albion Waterworks nearby.

A similar situation existed on the Starkweather farm, near Eagle Harbor. At the time of the canal expansion in the late 1800s, both Starkweathers and Lattins were offered a choice of keeping the private bridge or accepting $1,000 from NYS to give up their bridge claim. Starkweathers accepted the latter, Lattins did not. And, today, the Lattin Bridge is the only canal bridge in the state still serving private property.

Eagle Harbor lift bridge, 2007

Eventually, during the construction of the 1862 Enlarged Erie Canal, and again in the 1900s for the Barge Canal, low bridges were eliminated and replaced with tall stationary bridges or hydraulic lift bridges.

In all, 17 lift bridges were built across NYS to carry vehicular traffic over the canal. Orleans County can lay claim to seven of those lift bridges: Prospect Avenue (Route 63) in Medina, Knowlesville Road, Eagle Harbor Road, North Main Street Albion, Ingersoll Street in Albion, Hulberton Road in Murray and East Avenue in Holley. The small sliver of canal crossing through the Town of Gaines is serviced by a lift bridge in Eagle Harbor and a tall stationary bridge at Gaines Basin Road.

Eagle Harbor Lift Bridge, 2021

In Part 2 of this article, we will look at the historic canal breach that occurred in the Town of Gaines.